BBC Question Time: factchecked

Question Time was in Uttoxeter this week. The panelists were: Conservative Party Chair Brandon Lewis MP, Labour peer Lord Prescott, Siemens UK CEO Juergen Maier, Novara Media journalist Ash Sarkar and Sunday Express journalist Camilla Tominey.

We looked at claims on: how many students fully repay their tuition fees, how many drop out of university, and how many refugees are coming to the UK.

About 17% of students are forecast to fully pay back their loans

“But in reality, the actual debts that have totalled up for those graduates, and to get them, is impossible. More than that, many of them are not paying it and won't pay it, so you’ve really got to ask yourselves, was it worthwhile?”

John Prescott, 22 February 2018

“It's approximately 15% of people will pay back their entire student loan.”

BBC Question Time audience member, 22 February 2018

These claims are correct—the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that around 83% of graduates will have some debt written off under the current system. So around 17% are expected to repay in full.

Tuition fee policies

The government announced this week it is going to conduct a major review into post-16 education, including university funding.

In 2012 the Coalition government raised the cap on tuition fees for undergraduate courses from around £3,500 to £6,000 for all universities, and to £9,000 in "exceptional circumstances". This increased to £9,250 in 2017/18, which now the majority of universities are charging at or near.

The 2012 reforms were broadly intended to shift more of the burden of payment away from public funding and onto graduates, improve student choice, and to set up a more progressive loan structure so that lower earning graduates would pay less.

A raft of changes have taken place since then which have both pushed up and down the amounts that graduates end up re-paying. These include the replacement of maintenance grants with loans—policies which have increased the debts of the lowest income students—and more recently the raising of the earnings level at which graduates have to start repaying their debts from £21,000 to £25,000.

Graduate debt repayments and the cost to the taxpayer

The average debt for students starting their degree is now just under £50,000, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies. This is more than double the average debt under the 2011 system.

It’s correct that many students won’t pay off this debt—the IFS estimates that around 83% of graduates will have some debt written off under the current system. So around 17% are expected to repay in full.

The latest estimate from the IFS is that the taxpayer may end up paying for around 45% of the loans of students starting in 2017. The increase in the earnings threshold pushed this up from about 31%.

Both of these estimates are uncertain and affected by things like future interest rates and changes in the jobs market.

So was the 2012 fee increase worthwhile? There are lots of different elements to consider and we’re not going to go into all of them here.

When it comes to the cost to the taxpayer, the 2012 system always expected that a certain amount of debt wouldn’t be repaid, but not as much as is currently forecast (though we're checking if the forecasts are comparable).

When the 2012 reforms were proposed, the government estimated that it would bear the cost of around 30% of student debt, which it said would “maintain progressive elements of the scheme”.

The IFS has said “the main beneficiaries from reducing fees would be high-earning graduates, as they are the ones making the highest repayments under the current system”.

Check out the House of Commons Library briefings and the Institute for Fiscal Studies if you want to find out more.

6% of young first-time students drop out of university after their first year

“One of the things that we’ve found since the introduction of 9K fees is a 0.5% year on year increase in the dropout rate. So you've got 6% of students who don't make it from first year to second year.”

Ash Sarkar, 22 February 2018

This is correct on the drop-out rate for young undergraduates, but not quite right on the rate of increase. The latest figures only go up to students who started in 2014/15, so we don’t actually know what’s happened more recently yet.

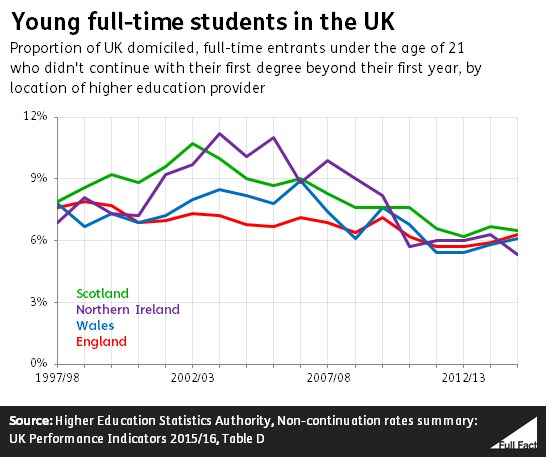

6.2% of UK young, full-time undergraduate students at university for the first time dropped out after their first year in 2014/15, up from 5.7% in 2012/13—the year that £9,000 tuition fees were introduced.

So that’s a 0.5 percentage point change over two years, not a percentage change year on year.

Drop-out rates also rose in Scotland after 2012/13, where students don’t have to pay fees, before falling back slightly in 2014/15. Scotland also has the highest dropout rate of UK countries at 6.5%.

These figures only cover students who don’t start their second year. Overall, it’s projected that 10.3% of students on their first degree will leave without a degree or being transferred to another programme, up slightly from 10.1% in 2012/13 but lower than as much as 16% in the late 1990s.

Drop-out rates are low historically, and higher for mature and disadvantaged students

These rates are still lower than the late 1990s and early 2000s, when the UK rate hit nearly 8% and in Scotland and Northern Ireland peaked at around 11%.

Overall mature students are more likely to drop out of full-time degrees than younger students. The same figures show 11.7% of mature first-time undergraduates dropped out in the UK in 2014/15, which was down slightly from 11.9% in 2012/13.

Disadvantaged students are also more likely than their peers to drop out. For the 20% most disadvantaged students, the rate increased from 7.6% in 2012/13 to 8.8% in 2014/15. We’ve factchecked the figures in more detail before.

We don’t know the exact reasons why dropout rates have crept up

The Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA)—which publishes the data on dropout rates—doesn’t have figures on why students are choosing to drop out of their courses.

The effect of tuition fee rises on dropout rates isn’t easy to predict, and there are actually arguments that increases in fees may reduce dropout rates because only students less likely to drop out in the first place may choose to apply.

This can work both ways though—the same researchers behind those arguments have also said in the past that the large increase to £9,000 a year could make students more reluctant to borrow money, and so increase dropout rates.

We can expect data on this subject later this year, so we’ll know a bit more then about the effect the 2012 changes may have had.

Two UK schemes have resettled 11,000 Syrian refugees

“We as a country are doing one of the biggest programmes we have ever done, 23,000 refugees coming to this country. We are slightly ahead of the schedule that David Cameron set out [...] There are 23,000 Syrian refugees coming to this country, on top of refugees from elsewhere.”

Brandon Lewis, 22 February 2018

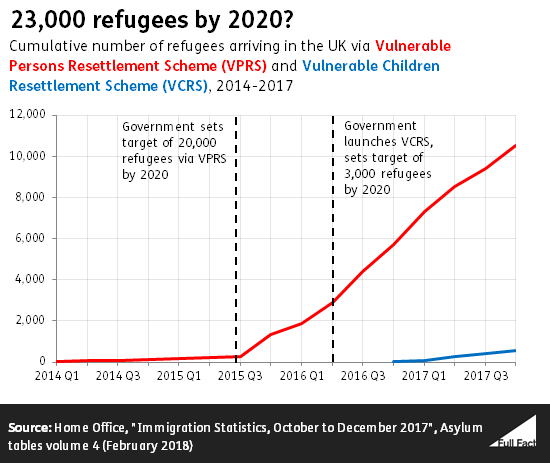

The government has said it aims to resettle 23,000 refugees in the UK from Syria and the surrounding region by 2020. So far, just over 11,000 refugees have come under two resettlement schemes, the first of which began in earnest in September 2015.

Prior to July 2017, those arriving on the scheme didn’t technically have refugee status in the UK, and instead had “Humanitarian Protection”. This gives individuals the right to five years’ residence in the UK, but not the full range of rights (such as access to benefits and support for Higher Education) that someone with refugee status has.

Of the 23,000 target, 20,000 are specifically from the conflict in Syria. The other 3,000 are vulnerable children and their families in the Middle East and North Africa.

These schemes aren’t the only way for refugees to enter the UK. Another 8,000 Syrian asylum seekers have been granted asylum after applying in the UK since 2011.

The Home Secretary yesterday claimed that the the government is “slightly ahead of schedule” in meeting the target to resettle 20,000 refugees from the Syrian conflict by 2020. This seems to be based on just over half of the target number having been resettled in roughly half the time since the target was set.

Some on the scheme don’t have refugee status

The Home Office told us that everyone who arrives via the government schemes fits the UN’s definition of a refugee.

But not all these people were granted refugee status by the UK. Prior to July 2017, they were granted Humanitarian Protection and five years’ stay in the UK. The government summarised the difference in status:

“while Humanitarian Protection recognises the need an individual has for international protection, it does not carry the same entitlements as refugee status, in particular, access to particular benefits, swifter access to student support for Higher Education and the same travel documents as those granted refugee status.”

Since July 2017, individuals on the scheme have been granted refugee status and five years’ stay in the UK. Those who arrived before that date may request a change to refugee status. Refugees in the UK normally get a residence permit for five years, after which they may apply for permanent residence.

For the rest of this piece, we will refer to all people arriving via a government resettlement scheme as a “refugee”.

What was the target?

The UK has two different resettlement schemes specifically for refugees from Syria and the surrounding region. Together, these two schemes aim to take in 23,000 people by 2020. Not all of these will necessarily be from Syria, though.

In September 2015, then-Prime Minister David Cameron announced “that Britain should resettle up to 20,000 Syrian refugees over the rest of this Parliament”.

The commitment to resettling 20,000 refugees by 2020 expanded the ambitions of the existing Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme (VPRS). Launched in January 2014 to help Syrian refugees, the VPRS had resettled 252 refugees between then and October 2015.

The scheme is meant to to identify, with the help of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “those most at risk and bring them to the UK”. It does not cover Syrian refugees already in Europe.

Since July 2017, refugees of any nationality fleeing the conflict in Syria may be considered for the VPRS.

The government announced a second resettlement scheme in April 2016. It aims to bring 3,000 vulnerable and refugee children and their families from the Middle East and North Africa to the UK by 2020. Now called the Vulnerable Children's Resettlement Scheme (VCRS), it covers unaccompanied and separated children, as well as “other vulnerable children such as child carers and those facing the risk of child labour, child marriage or other forms of neglect, abuse or exploitation.”

Those arriving through both schemes are granted five years’ stay in the UK.

These schemes are not the only way enter the UK as a refugee. An individual may apply to the UK as an asylum seeker. An asylum seeker will then have their case considered by the government, to determine whether or not they are a refugee under international law.

What has happened so far?

Government figures released yesterday show that, by December 2017, roughly 10,500 refugees from the Syrian conflict have been resettled under the VPRS. The vast majority were resettled since September 2015. Almost 5,000 were resettled in 2017, and roughly half of them were children.

570 people have been resettled under the VCRS, 539 of whom were in 2017.

In addition to this, over 8,000 Syrian asylum seekers and their dependants were accepted refugges in the UK from 2011 to 2017. This means they applied for protection in the UK, rather than having been identified through a government scheme. Overall there were an estimated 119,000 refugees in the UK at the end of 2016, according to the UN.

Globally, there are 5.6 million refugees from Syria. 3.5 million are registered in Turkey, and a further two million are in Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and Lebanon according to the UNHCR. 63% of Syrian asylum applications in Europe were made to Germany or Sweden between April 2011 and December 2017.

Ahead of schedule?

The Home Secretary yesterday claimed that the government is “slightly ahead of schedule” in meeting the 20,000 target. We asked the Home Office for more information on this but they didn’t provide any further detail.

Just over 10,000 refugees have arrived in the UK via VPRS, based on figures up to December 2017. The target was set in September 2015, with an end-date of 2020—so just over half the target has been met in roughly half the allotted time period. We don’t know if the pace of resettlement is expected to be the same across the whole period to 2020.