Q&A: Can we still trust crime statistics?

Crime is falling. Probably.

Yet, according to the BBC and others this morning, it might not be falling as fast as we might think. The BBC reported that trends of decline may be "exaggerated". Then the Labour party added its own emphasis to the story:

"The Home Secretary should examine urgently whether, as the ONS suggest, the cuts to police budgets mark a return to fewer crimes being recorded by the police."

A few questions may be on readers' minds. Let's try and answer a few.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

So crime is falling? Prove it.

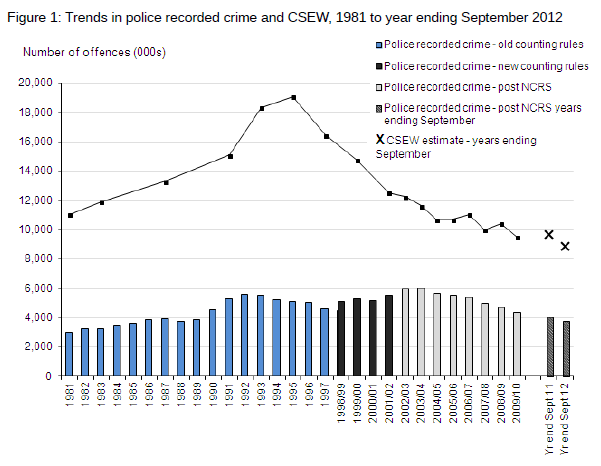

Both methods of measuring crime (the Crime Survey of England and Wales (CSEW) and police-recorded crime) have shown a decrease in crime over the past decade. As the graph below shows, since the National Crime Recording Standard (NCRS) was introduced in 2002, police records have consistently shown year-on-year falls in recorded crime.

Why is there such a difference between the two estimates?

The Crime Survey always detects more crime than police records because a lot of crime that is experienced by the public doesn't get reported to the police. As today's Office for National Statistics (ONS) release showed, 61% of crime experienced by the public in 2011/12 went unreported.

There are also some small variations in what the two methods measure. The Crime Survey doesn't measure drug possession, for instance, as this doesn't have a direct victim, nor does it count homicides as a respondent to a survey can't recall having been murdered in the past year. Police-recorded crime, meanwhile, isn't very good at detecting crimes with a low rate of reportage, such as domestic violence.

So what's the problem everyone's talking about?

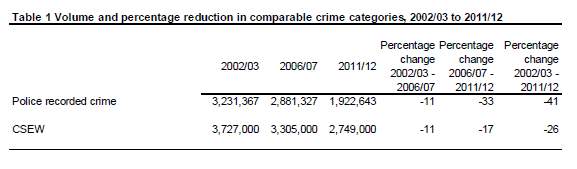

In spite of the differences between the two methods, there's no good reason to expect either set of figures to show a significantly different trend over time than the other. Even though both measures have shown declining trends in crime, police-recorded crime has fallen by twice as much as similar crimes measured by the Survey since 2006/07.

The table above is from the ONS's own analysis of "comparable crime categories". As the ONS makes clear, there is a sizeable caveat. Making survey responses and police records compatible for a comparison is difficult not least because the 'victims' aren't the same (the Crime Survey only applies to household victims rather than commercial businesses, for instance).

Respondents to a survey also can't always be relied upon to recall information correctly - they may forget crimes occurred or recall a crime that happened outside of the survey's timeframe.

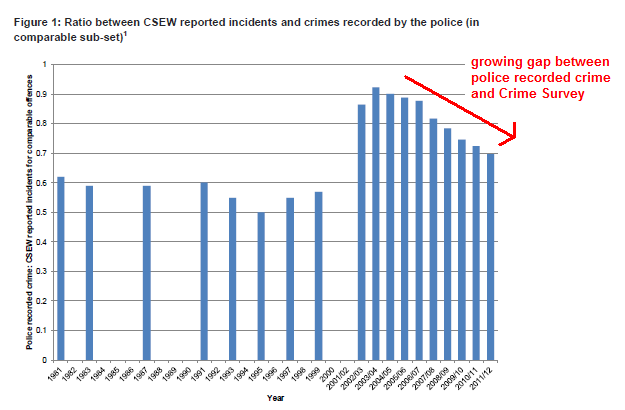

The ONS express the problem in a graph which shows that the ratio between police records and Crime Survey estimates is growing constantly:

Does this mean the police are detecting too little crime? Or is the Crime Survey over-estimating what crime there is?

The ONS largely rule out the possibility that the Crime Survey is responsible for the growing gap. There haven't been any significant changes to the methodology of the survey, the contractors carrying out the survey haven't changed, the profile of respondents hasn't changed, and the response rates have remained steady.

So the police are to blame? Is this an impact of the Government's cuts?

It isn't possible yet to provide a definitive answer as to why police records are seemingly missing thousands of crimes. The ONS do, however, offer five possible explanations:

1) Slipping standards: The police's own awareness of recording standards is declining, perhaps because of poor training for new officers.

2) Meeting targets: Performance targets are causing police to 'downgrade' crimes to anti-social behavour, which isn't a 'recorded crime', so that it appears as if crime is falling.

3) No one's watching: There's been no system of regular, independent checks of the police's recording methods since 2007.

4) More informal enforcement: 'Neighbourhood policing' is leading to more crimes dealt with outside the formal recording system.

5) Tightening budgets: Cost pressures are leading to different methods of recording and resolving crimes.

As is apparent, budget cuts are only one of many possibilities, and the ONS state quite clearly:

"The above analysis cannot provide a definitive answer to these points or confirm or disprove these hypotheses."

So who should I believe?

For now, any 'reasons' for the divergence crime trends being reported are unlikely to be much more than speculation. There is a convincing case that a problem exists, but the cause of the problem is yet to be reliably determined.

Can I still trust crime statistics?

Yes. As the ONS state, the system for recording crime in England and Wales is widely recognised by international standards as one of the best in the world. This doesn't mean it's free of problems and issues like these still need to be resolved, but there's no reason to rubbish the figures.