How accurate are immigration statistics?

The UK's migration statistics are "little better than a best guess," according to a committee of MPs.

Party spokesmen joined in with such extreme differences of opinion as to their worth — "accurate" and "very robust" from the Minister but "a bit dodgy" from the Shadow Minister — that it's tempting to give up on the whole argument.

Yet this assertion, which made headlines over the weekend, is arguably either not true or not surprising, depending on what you think the purpose of migration statistics is.

Statisticians have been warning for a long time that you cannot expect to get a precise count of migration using the methods we do.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

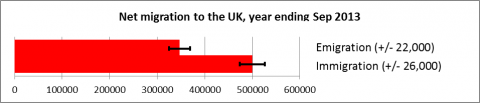

As Sir Andrew Dilnot of the Statistics Authority explained to the Committee, net migration is the relatively small difference between two relatively large numbers, and both sets of figures are uncertain.

That's why individual estimates are considered accurate only to within plus or minus 34,000, although he points out that viewed over time they seem fairly consistent.

About 100 million people arrive in the UK every year, and about 100 million leave. Annual net migration of 153,000 people amounts to a fraction of the number who come in or out on an average day.

Of that 100 million, the statisticians who conduct the International Passenger Survey interview around 800,000 willing passengers, including around 5,000 migrants. That needle-in-a-haystack sample is the starting point for our estimates of migration.

To make these estimates twice as accurate — so that 19 times out of 20 they are within 17,000 of the correct figure — you would need to quadruple the sample size to 3.2 million. MPs were told that would cost £15m but the Chair of the Committee commented "I think that would be very bad value for money."

When passenger surveys began, statisticians simply assumed that anyone below decks on a long-distance ship was a long-term migrant. Things have become more sophisticated since.

A 2006 taskforce led to an improvement programme, which is still on-going and which was reviewed by the Statistics Authority in 2009, 2011 and again this year. This includes changes to the survey design, how other data is used to test and improve the conclusions and how the data is published. Further improvements are planned.

The latest conclusion from the independent Authority is that migration data is "sufficiently robust" at a national level but not, as its Chairman wrote to the Select Committee, for two "particularly demanding uses."

One, unfortunately, is assessing performance against the government's target of reducing net migration to the "tens of thousands," a new feature of immigration policy since the election. Tens of thousands give or take tens of thousands isn't much of a target.

The other is providing estimates of net migration at local authority level, which is of great importance because it affects the funding they receive.

What the Authority did say they were good for is population estimates, which affect planning for public services and economic management; international comparisons; and even assessing performance against the migration target "in longer-term perspective".

Although "little better than a best guess" made the headlines, the Committee wasn't suggesting that the statistical methods are themselves flawed, unprofessional or "dodgy".

The report's summary says that the International Passenger Survey doesn't stand up to "the purposes to which it is put." The estimates "are too uncertain for accurate measurement of progress against the Government's net migration target," it says, and "do not provide accurate estimates of international migration to and from local areas."

That is politically important, but not news to those who produce or work with the statistics.