Social care: a postcode lottery

In certain parts of England, how you're cared for in your old age depends on which side of the street you live on.

Many people are shocked to discover that social care is not free at the point of use - unlike the NHS. The Health Service will pick up the bill if you're elderly and in need of hospital treatment; but if you're too frail to get out of bed in the morning or you can't cook for yourself any more, then you'll probably have to pay for any help you require.

That is unless the local authority assesses your needs as being severe enough that you're entitled to social care (although even then you'll need to qualify via a means-test to receive assistance). 83% of local authorities in England only provide care for those with "substantial" or "critical" needs. If you're entitled to support, you might be cared for in a residential home (residential care) or you'll remain in your own home, where you'll either be visited by a care-worker (home care) or recieve care at a neighbourhood centre (day care).

For residential care, a local authority will pay a "standard" fee to a care home, per person per week. It then calculates how much of its overall budget it's able to spend on home care and day care.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

A local authority is free to choose how much money it will allocate to social care, as long as it meets the needs of those it has assessed. This means that where you live - your town, your street, even your house number - will decide what support you're likely to receive.

Shenley Road skirts the edge of the village of Bletchley and crosses the local authority boundary between Milton Keynes and Buckinghamshire. If you live on the stretch of road that passes through Milton Keynes and you need to be admitted to a residential home, the local authority will pay a standard fee of £487 per week for your care. Half a mile on, in Bucks, the local authority would contribute up to £871 per week to your costs.

In setting a standard limit on how much it will pay for an individual's care, a local authority ought to account for various costs — including the number of local people in need of care, the price of living in the area and the wage-levels of care workers in the region. In certain cases, the local authority is obliged to pay extra for a person's care — for example, if it needs to place someone in residential care and the only care home with vacancies charges a fee that's more than its standard rate.

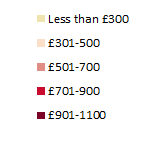

When we look at a map of residential care costs, it's hardly surprising that across the country there is wide variation in the level of provision (at least, nominally - in terms of the amount of money allocated per head). However, in some areas there are big differences in how much money neighbouring councils will spend.

In London, the comparison is particularly startling. The City of London pays a standard rate of £1029 per week for a person's residential care; the borough of Newham, 2 miles away, offers less than half that amount.

Residential Care Costs (2010/11) - amount spent per person per week

Click on the local authorities to show a cost breakdown.

We find that many of the local authorities with higher rates are located in the south east. This is likely to be a reflection of the fact that the cost of living is more expensive in these areas. Across England, the average is £623 per person per week.

We might expect care costs to be broadly similar across a particular region. But because the government doesn't have a policy on what constitutes a "fair price", it's up to each council to make a judgement call. This is the localism agenda in action — a council decides its own spending priorities.

In recent years, many local authorities have raided their social care funds: money that in a time of surplus would have been spent on social care has now been allocated to resurfacing roads or keeping the doors of the local library open.

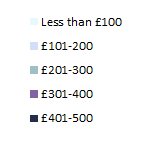

It is normally cheaper for local authorities to provide home care (the average cost for England is only £204 per week) because the people receiving it tend to be those with less intensive needs. They might need help with bathing, for example, but they won't require 24 hour care. But when we look at the map of home care costs, we can see that there's still no consistency in how much a local authority will spend.

Home Care Costs (2010/11) - amount spent per person per week

Click on the local authorities to show a cost breakdown.

A local authority that funds a high fee for residential care will not necessarily pay more towards every type of care. If you live on the Isles of Scilly, the local authority would spend up to £895 per week on your residential care - in this regard, it's one of the highest spending authorities. However, if you were to be cared for in your own home, the local authority's rate is £140 on average - this puts it in the bottom 10% of authorities for home care spend.

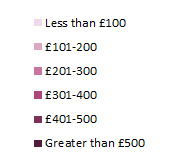

Day care, which includes the activities of neighbourhood centres, is the cheapest form of care to provide (the average cost is £198 per week). Certain local authorities - West Sussex, for example - spend more money across the board, whether it's residential care, home care or day care; others will prioritise spending on certain types of care - Suffolk, for instance, is one of the lowest spending local authorities for day care, but spends more than the average on home care.

Day Care Costs (2010/11) - amount spent per person per week

Click on the local authorities to show a cost breakdown.

In his 2011 report into the future of social care funding, the economist Andrew Dilnot argued that the current system amounts to a "postcode lottery". These maps illustrate the huge disparity across the country in the amount of money spent per head on social care.

It's more problematic to draw conclusions about how the standard of care differs from area to area. Just because a local authority is spending less on social care doesn't mean that the care it provides is of poorer quality.

Some authorities will offer an excellent standard of care to local residents who are in need - and these may not be the councils with the largest social care budgets.

However, in certain places the standard rate for residential care is so low that we might reasonably ask how it's possible to ensure decent care. We might expect these local authorities to be heavily reliant on so-called "third-party top-ups", when someone's relative or a charity is asked to pay extra for an improved quality of care. In the coming months, Full Fact will be investigating how this hidden economy operates.

Since the publication of the Dilnot report the government has committed itself to tackling the inequality that's built into the current framework, although it hasn't yet explained how it will do this. These maps demonstrate the unfairness that many would argue is the defining feature of our social care system.