Benefit fraud: Has DWP hotline increased prosecutions?

"The Government says 20 per cent more cheats were caught in the past 12 months than in the last year of Labour." Daily Express, 5 December 2011.

The Daily Express ran an article today about a 'new blitz on benefit cheats' in the form of an anonymous phone line set up by the Government in combination with Crimestoppers which allows callers to report suspected benefit fraudsters.

Within the article, it claimed the National Benefit Fraud Hotline receives more than 700 calls per day. The result, the article suggested, was that the Department for Work and Pensions had prosecuted more than 10,000 benefit fraudsters, saving some £100 million since October 2010.

These figures represented an increase of 20 per cent more benefit cheats being caught in the last 12 months than Labour managed in their last year of government, according to the Express.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Is the hotline proving to be as successful as the Express claimed?

Analysis

Turning first to the assertion that the hotline receives over 700 calls per day, the Express credits an announcement from last week as the source for this claim.

While the Work and Pensions Secretary Iain Duncan Smith did respond to a written question last week in the House of Commons about benefit fraud, this figure was not discussed.

The most recent statistic we could find on the number of calls received by the hotline was in a written answer on 7 March this year, where the Employment Minister Chris Grayling stated that in 2009 to 2010, 253,708 cases of suspected benefit fraud were reported to the DWP hotline.

Of these, 46,258 were referred to the Fraud Investigation Service for further action.

Using the figure of 253,708 over one year, this represents an average of 695 calls per day. It is possible that this is the figure to which the article was referring.

Next, to consider the number of benefit cheat prosecutions.

In the House of Commons last Monday, Mr Duncan Smith referred to a strategy started in 2010 to tackle benefit fraud using mobile regional taskforces which focussed on claimants in high fraud areas. This scheme, he said, meant that, "since October, from case cleansing alone we have saved more than £100 million."

He also said that almost 10,000 benefit fraudsters were prosecuted in 2010/11, up from 8,200 the year before. While the Express attributes this to the same time period as the savings of £100 million, it is more likely to refer to the 2010/11 financial year.

The Express uses these statistics to show an increase of 20 per cent in prosecutions of benefit cheats under the coalition Government as compared to the last year of the Labour government. The increase of 1,800 prosecutions represents a 22 per cent increase from 8,200.

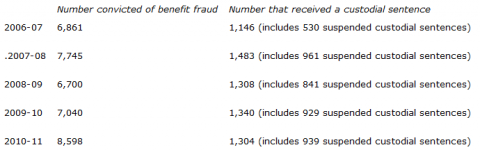

The number actually convicted is slightly lower than this but still represents around a 20 per cent increase in benefit cheat convictions from 2009/10 to 2010/11. In a House of Commons Written Answer in October 2011, Mr Grayling provided the following statistics:

The rise of 1,558 from 2009/10 to 2010/11 represents a 22 per cent increase.

The statistics in the Express article therefore were correct. However, were they correct to attribute the improvement of prosecution to the benefit fraud hotline?

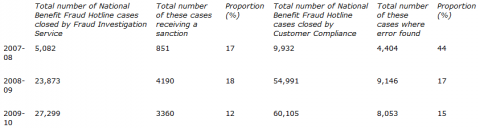

In a Written Answer on 5 April this year, Mr Grayling stated the number of National Benefit Fraud Hotline cases closed each year as of February 2011. The following table shows these statistics:

Taking the number of cases closed by the Fraud Investigation Service in 2009 to 2010, just 12 per cent received a sanction. Given that the proportion only refers to those cases actually passed onto the Fraud Investigation Service from hotline calls, rather than the total number of calls, a surprisingly small proportion of cases actually received a sanction.

A sanction refers to cases which will receive a penalty of some form but does not necessarily lead directly to conviction. Therefore we cannot compare the number receiving a sanction as a result of the hotline to the number being convicted, which makes it hard to assess what contribution the hotline is making to prosecutions of benefit fraudsters.

Conclusion

The statistics mentioned in the Express article do appear to be correct, although the impact of the fraud hotline may be more muted than it suggests. The savings of £100 million and the prosecution of almost 10,000 benefit fraudsters should not be represented as co-dependent since they refer to overlapping time periods, rather than the same time periods.

While we cannot comment on what how large an impact the hotline has on the total number being prosecuted, the statistics do show that a surprisingly small proportion of cases from the hotline are receiving a sanction.