What effect has decriminalising drugs had in Portugal?

"Richard Branson is not only wrong; he's dangerously wrong. For example he's so dangerous he's persuaded some of these good people in the audience that Portugal since it decriminalised drugs has had great success...

The very opposite is the case ... since Portugal decriminalised drugs, drug use there has gone up, the number of people using drugs has gone up, the number of homicides related to drug use has gone up by 40 per cent, and drug-related HIV/AIDS and Hepititis C is up and the rate in Portugal is now eight times that of EU countries"

Melanie Phillips, BBC Question Time, 26 January 2011

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Last week Virgin chairman Sir Richard Branson appeared before the Home Affairs Select Committee as part of their inquiry into drugs policy. Sir Richard, who is a commissioner in the Global Commission on Drugs Policy, prominently featured Portugal as an example of a successful national drugs policy. Portugal decriminalised illicit drugs in July 2001.

The appearance was well reported and the topic eventually made it onto the BBC's Question Time programme. After an audience member brought up the example of Portgual, Melanie Phillips blasted the example, citing several statistics condemning Portugal's decriminalisation policy, such as increased drug use and mortality rates.

So what can we say about the Portuguese example of drug decriminalisation?

Number of drug users

Sir Richard Branson's figures can be found in the "War On Drugs" 2011 Report from the Global Commission on Drug Policy.

Some of figures used by Melanie Phillips are drawn from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) World Drugs Report from 2009. Page 168 of the report states of Portugal:

"Portugal did experience an increase in drug use after [decriminalisation] was implemented, but so did many European countries during this period. Cannabis use increased only moderately, but cocaine and amphetamine use rates apparently doubled off a low base."

These figures from UNODC are originally sourced from the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) which compiles statistics on countries' drug usage. Examining the figures revealed that the prevalence of drug use is measured either based on findings from the last month, last year or over a whole lifetime. Portugal's figures are available from surveys conducted in 2001 and 2007.

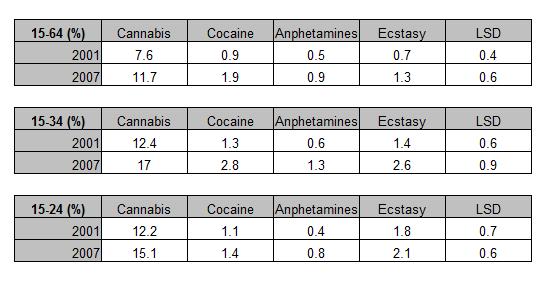

Taking lifetime prevalence (shown below) demonstrates that the proportion of all adults taking various drugs has increased on almost all counts.

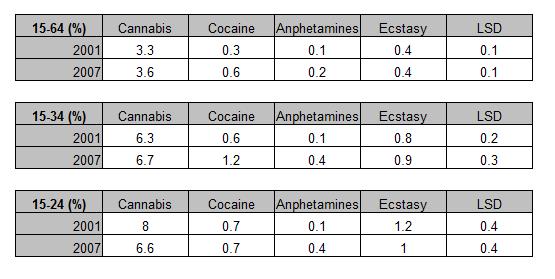

However, there is some debate over whether 'lifetime prevalence' is an appropriate measure given that this would include drug taking that took place before 2001 for many respondents. To gage the post-reform changes, it is also indicative to consider the annual prevalence. This is shown below:

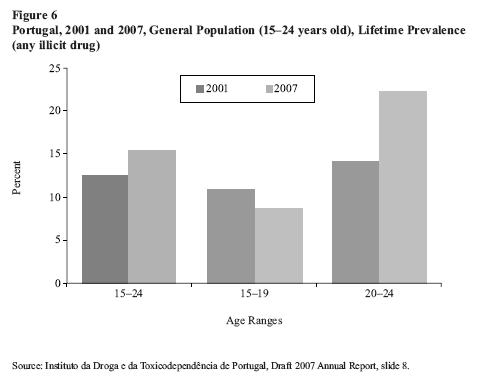

A much-cited paper by Glenn Greenwald from the Cato Institute in 2009 (although also the source of controversy from, among others, the US Office of National Drug Control Policy), also examines these figures for more specific age groups. These demonstrate a counter-trend amongst 15 to 19 year olds - hence the source of some claims that usage has decreased in some quarters:

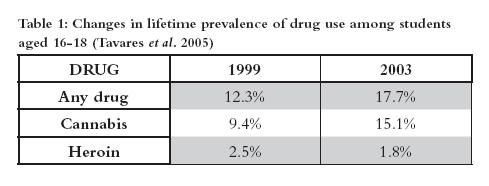

Furthermore, a 2007 paper by Caitlin Hughes and Alex Stevens cites research from Tavares et al (2005) that measures changes in lifetime prevalence of just those aged 16-18 - this time in 1999, two years before the law changes, and 2003, two years after:

Among this narrow age group, the number of Heroin users seems to have declined slightly after decriminalisation.

Drug-related homicides

Another of Melanie Phillips' claims is mentioned in the UNODC 2009 report:

"The number of murders increased 40% during [2001 - 2006], a fact that might be related to the trafficking activity."

Eurostat's 'Statistics in Focus' provides the data on homicides for most European countries. Examining this data reveals the homicide rate in Portugal has increased from 105 to 148 per 100,000 population - a 41 per cent increase. The general trend across most of the other European countries is a decline in homicide, except in Ireland, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Sweden and Scotland.

However, the definition of homicide provided by the data is: "defined as intentional killing of a person, including murder, manslaughter, euthanasia and infanticide." There is no mention of drugs as a cause or involvement in the deaths. The only evidence comes from the UNODC's mention of "might be related to the trafficking activity". However this is hardly a solid foundation for assuming the murders are drug-related.

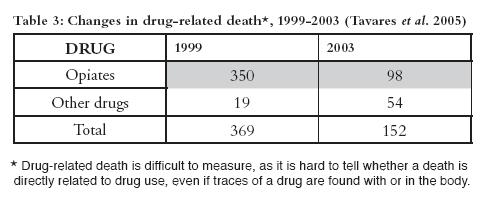

Data can again be drawn from Tavares et al via the Hughes/Stevens paper. While the caveats and limitations of these data need to be noted, they show that between 1999 and 2003 there was a marked decline in drug-related deaths in Portugal.

The most recent data from EMCDDA shows the total number of drug-related deaths in 2009 was 54, down from 94 in 2008. There is however no data available for earlier years. These datasets are not necessarily comparable.

Drug-related infectious diseases

Ms Phillips also pointed out rises in drug-related infectious diseases (DRID), specifically those in HIV and Hepititis C.

The figures from EMCDDA show that estimates of HIV infection ranged from 13.6 - 16.8 per cent of injecting drug users in 2001. By 2009, these ranged from 6.7 - 17.2 per cent. While different measures were used in each case, most of the measures taken in isolation showed falls in infection rates. Prevalence of Hepititis C among new injecting users also showed a small but volatile decline.

However, the number of possible datasets that can be used is considerable. The EMCDDA's profile on Portugal nevertheless summarises:

"In general, a decreasing trend in the percentage of drug users in the total number of notifications of HIV and AIDS cases continues to be registered (since 1999—2000). Likewise, the decline in the incidence of HIV and AIDS among IDUs is also registered since 1999—2000 (142 new HIV cases in 2009 and 1,482 in 2000; 70 new AIDS cases in 2009 and 675 in 1999). A downward trend can be observed also in the prevalence of HIV, HCV and HBV among clients of the drug treatment settings."

So on this count Portugal appears to be performing better than implied by Ms Phillips, although we cannot say to which specific measures she was originally referring.

Conclusion

The academic debate over Portugal's performance following decriminalisation remains considerable and hotly debated. Full Fact found many of the problems stemmed not necessarily from a disagreement over the facts but a disagreement over which facts matter when it comes to interpreting the effects of decriminalisation.

In addition to this, how these post-2001 trends compare to trends beforehand is also a relevant factor in the debate, as is the comparison with other European countries that have not followed Portugal's policy. Both are beyond the scope of this particular factcheck.

As for the trends that Melanie Phillips referred to, there is very much a mixed bag of figures. The prevalence of drug use has indeed increased, with only a small number of exceptions in narrower age bands. UNODC also highlight a large increase in cocaine seizures: seven-fold between 2001 and 2006.

Portugal's homicide rate bucked the European trend by increasing in the 2000s, but there seems to be little evidence that explicitly links this to drug usage, and on this count Ms Phillips' comments do not appear to paint the full picture. Drug-related deaths, specifically measured, indicated a decline in mortality from most drugs. Furthermore, infections from certain diseases also seem to have fallen, although again this is based on specific figures.

There is a considerable range of studies available - some mentioned here - that analyse the recent trends in the context of trends before decriminalistion took place in 2001. Only by taking these arguments into account can one infer the causal effect Portugal's policy has had on the effects of drug use in the country.