What can Love Island tell us about survey design?

It’s day 50 on Love Island. We’re reaching the tail end of the hit ITV2 show where toned, Instagramming twenty-somethings are stuck in a Majorcan villa and told to find love or face being voted out by the public, missing out on the £50,000 prize.

Not a typical place to look for lessons in survey design, but then, to quote the Grateful Dead, once in a while you get shown the light in the strangest of places if you look at it right.

To set the scene, the boys are taking it in turns to be hooked up to a lie detector of questionable accuracy and grilled by their partners on the strength of their relationship.

Nuclear systems engineer Wes is in the hot seat and asked: “Are you embarrassed to take Megan home to your parents?” to which he immediately answers “no”.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

The detector gives back a cringeworthy “undetermined” verdict.

Like any social researcher worth their salt when faced with data they don’t like the look of, Megan turns on her own survey design and suggests she can’t trust the result:

“It’s like [asking] “are you embarrassed of my past” and “do you want to take me to meet my parents” all in one.”

And she’s right to note that when asking these sort of questions, known in the industry as “double-barrelled” or “compound” questions, the data you can get doesn’t tell you much.

That’s because you can’t know whether the data you get is in response to the first half, second half or both parts of the question.

For example, Wes might not want Megan to meet his parents yet, but not because of embarrassment.

Trivial, yes. But bad survey design can shape national conversation about important political issues.

For example, back in May the Daily Express’s front page contained details of a poll exploring the public’s political views and views of life in Britain. We factchecked the results at the time.

One question asked people whether they agreed or disagreed that: “Theresa May might not be the most exciting politician but she is the right person for the job at the moment.”

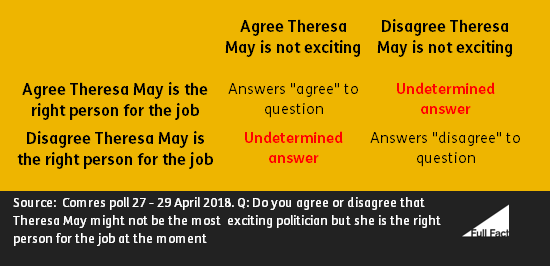

This essentially asks people whether they agree or disagree with two things:

- Theresa May is not the most exciting politician.

- Theresa May is the right person for the job at the moment.

The question is really trying to ask how many people think Theresa May is the right person to be Prime Minister at the moment. But because of that first part of the sentence and because you can agree with one statement and disagree with the other, it’s hard to interpret the data.

To summarise, this table shows how we can’t be sure whether the 43% who agreed is the right figure for those who feel Theresa May is the right person for the job.

So while the post-show world of celebrity beckons for the inhabitants of Love Island, there could be a future for them as polling consultants.

Though given the existential panic that beset the villa when told on Wednesday what the public thought of them, without any of them questioning the sample selection and affirmation bias, perhaps there are lessons still to be learned.