Reporting on childhood diabetes prevalence should come with a health warning

If you looked at the news or social media yesterday, you may have seen stories from newspapers and broadcasters reporting a “shocking rise in child diabetes”, with 7,000 under 25s diagnosed with type 2 diabetes in England and Wales.

The Express, which first reported the story on its front page, continues: “The total is 10 times the number officially recorded as being referred to specialist paediatric units, meaning the problem is significantly worse than first feared.” The BBC also writes that the figure is “about 10 times the number reported before”.

But does this really mean there’s been a tenfold increase? No.

Type 2 diabetes has risen among children and young people in recent years, but not by ten times. (Based on the evidence for a slightly different age group, the real increase might be closer to 1.5 times.) That ten times “increase” is just a result of looking at a different set of data that includes a lot more people in it.

And these aren’t exactly “new figures”, as several reports claimed―something that Full Fact readers will know, because we wrote about it two months ago.

Previous reporting has focused on an unrepresentative data source

We wrote an article in early September on this exact issue (although it was looking at a different age range: under 20s, not under 25s).

Back then we were factchecking the Times, which reported that “the number of children and teenagers needing specialist treatment for type 2 diabetes has risen by 40 per cent in four years.”

That’s technically correct, but there were problems with the figures used to back it up. The Times’ article was based on information from an audit of paediatric units produced by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH).

But not all children and young people with type 2 diabetes are treated in paediatric units; those over 16 may be referred to adult services instead, and many are treated directly by their GP. And so the data won’t capture all the people in that age group who have the condition.

The RCPCH themselves say: “Prevalence and/or incidence rates of Type 2 diabetes cannot be accurately calculated from NPDA data as an unknown number of children and young people are treated for Type 2 diabetes in primary care [e.g. GPs] and will therefore not be included in the audit.”

In our factcheck, we pointed out that there was far more comprehensive data available from NHS Digital, which comes from an audit of almost all GPs in England and Wales.

The charity Diabetes UK recently did a similar analysis for the under 25 age group, which resulted in the flurry of news stories yesterday. They did this by combining the GP audit data with the data from the paediatric units–producing the “new figures” the media reports referred to.

But to suggest, as the Express does, that “before this the most reliable data was from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health” is a bit misleading. The NHS Digital national diabetes audit is described as “one of the largest annual clinical audits in the world” and “the most comprehensive audit of its kind”, and reports from it are available going back to 2003/4.

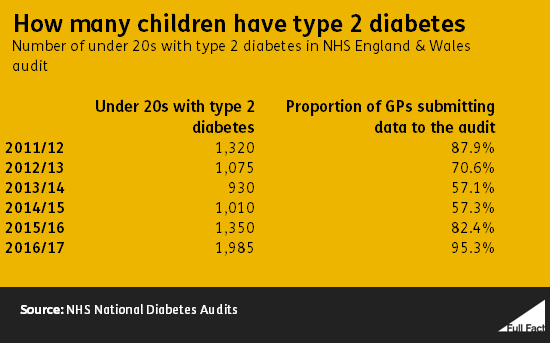

Data on children with type 2 diabetes isn’t directly available from the latest published data, because children with type 2 are grouped with children with other diabetes types (those that are neither type 1 nor type 2). Back in September we had to ask NHS Digital to separate those figures out for us. But figures on type 2 data are available from the audit for previous years. These figures aren’t perfect either, as we wrote about at the time, but they do give us a much better picture than the figures from RCPCH.

We found that the number of under 20s in England and Wales with type 2 diabetes recorded in the audit was 1.5 times higher in 2016/17 than in 2011/12.

That’s a long way off the “ten times” increase suggested in the Express (even if that referred to a slightly different age group—under 25s rather than under 20s).

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

The rise in childhood diabetes is a real and important issue, and the work from Diabetes UK combining the two data sets is useful. But media reports that imply there has been a tenfold jump in the figures, when the basis for that is simply historical reporting that looked at incomplete data, isn’t helpful for understanding the true scale of the problem.