Do a quarter of sickness benefits claimants have a criminal record?

"Almost one in four people claiming sickness benefit have criminal records, an official analysis showed yesterday...

"The findings from a Government research project show a high proportion of claimants who claim they are unfit for work appear to be fit enough to commit crime."

Daily Mail, 20 July 2012

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Are a quarter of people claiming 'sickness' benefits fit enough to commit crime?

That was the claim that emerged in the Daily Mail this Saturday, citing an "official analysis [released] yesterday" as proof.

Confusingly, no such story appeared on the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) website on Friday. However several suspiciously similar stories about benefit claimants did appear at the end of last year: The Mail, the Star, the Express, and the Telegraph all reported the findings of joint research by the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) and DWP into the link between benefit claimants and criminality, while Employment Minister Chris Grayling gave a similar quote to that in Saturday's Mail.

A quick call to the DWP press office confirmed that these were the figures in question, with the Mail seemingly mixing up its timings. So dating aside, do the claims stack up?

Analysis

The 'Offending, employment and benefits — emerging findings from the data linkage project' report combines HMRC data on individuals' employment status, DWP data on benefits claims, and MoJ data on sentencing.

This makes it possible to trace the employment and benefit history of individuals who have been cautioned for or convicted of offences. In total, 3.6 million people who received a caution or conviction in England and Wales between 2000 and 2010 and have a benefit and/or employment record during the time are included.

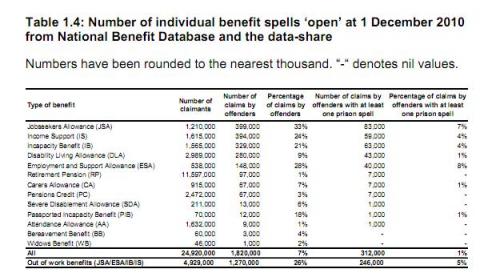

Table 1.4 of the report shows that of the 1.6 million people receiving Incapacity Benefit on December 1 2010, 21 per cent had received a caution or conviction in the previous 10 years, as the Mail reported.

The same table shows that 28 per cent of Employment Support Allowance recipients (ESA is replacing Incapacity Benefit) have a criminal record, although these figures can't be added together.

The Mail's headline that a "quarter of those claiming sickness benefits have a criminal record" is broadly accurate, with slightly fewer than one in four IB claimants having criminal records and slightly more than one in four ESA claimants having likewise.

But what about the suggestion that these people are claiming to be too ill to work while being fit enough to commit crime?

Here it gets trickier. Someone could have been convicted of an offence in 2001 and legitimately claimed incapacity benefit in 2007, but they would show up as an IB recipient with a criminal record even though the criminality occurred several years before the person started claiming benefits.

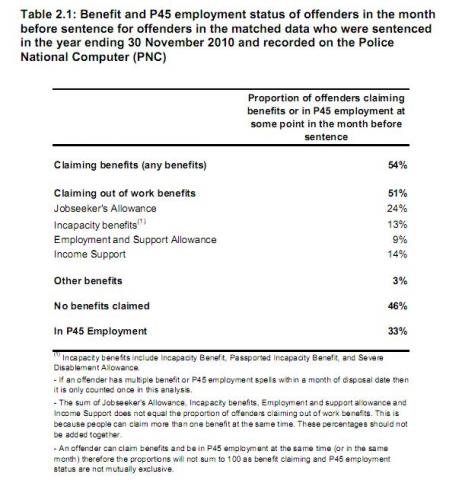

A better way to measure this might be to look at whether offenders were claiming benefits near to the time of their sentencing. Table 2.1 shows that 13 per cent of people sentenced claimed incapacity benefits — a wider category that includes Incapacity Benefit, Passported Incapacity Benefit, and Severe Disablement Allowance — in the month before they were sentenced:

This is still subject to caveats. The report's methodology notes that not everyone recorded as being on a benefit will necessarily be receiving it:

"An individual can be recorded as having a spell on a benefit and usually that will mean that the individual is in receipt of a benefit payment. However, there are exceptions to this, particularly for individuals claiming Incapacity Benefit or Disability Living Allowance. An individual can be recorded as being on a particular benefit but they are not in receipt of payment as they do not meet the full conditions at that particular time."

There can also be a long period between an offence being committed and sentencing, which could underestimate numbers on benefits:

"For a number of reasons, it is possible for offenders to be convicted (found guilty) and for there to be a delay between the conviction and sentence date. In these instances, it is possible that benefits are stopped or P45 employment spells are ended as soon as the offender is convicted. Therefore this analysis may underestimate the proportion of offenders who are claiming benefits or in P45 employment, and care should be taken when interpreting the findings."

Nevertheless, this looks like the best available measure of how many people claiming sickness benefits commit crime: 13 per cent, or one in eight. However it's also worth pointing out that being able to commit a crime does not necessarily mean someone is fit to work. Certain crimes, such as drug possession, could be committed by incapacitated and 'fit' offenders alike.

How significant this figure is can be disputed. As others have pointed out, the Chartered Institute for Personnel and Development (CIPD) has claimed that a quarter of the general population have a criminal record.

It's surprisingly difficult to find data on the proportion of the general population with criminal records that might support this claim.

An answer to a Parliamentary Question in 2008 points to research from 2001 which followed the fortunes of groups of people born between 1953 and 1978. By 2001, 33 per cent of male subjects born in 1953 had convictions, as did 9 per cent of women — although it doesn't give an overall percentage. The most recent cohort, however, seems to be picking up convictions rather slower than the others, as the chart below shows:

These figures don't include cautions, however, making it difficult to compare to the DWP research — a task made harder by the fact that the DWP's study only looked at a decade.

Nevertheless, it is certainly not clear that the incidence of criminality is higher among benefit claimants than it is elsewhere, and it may in fact be lower.

Conclusion

The Mail is correct in stating that 21 per cent of incapacity benefit claimants committed an offence of some sort between 2000 and 2010.

However, it's on shakier ground in saying these people "claim to be unfit for work [but] appear to be fit enough to commit crime", as only 13 per cent of offenders claimed a sickness benefit in the month before they were sentenced.

It's also dubious as to whether these are "truly alarming" figures as the article claims, and when compared to the best information we have on the prevalence of criminal records in the general population, the claim seems less striking.