Hate crime in England and Wales

Join 73,000 newsletter subscribers who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

No single definitive figure for hate crime

There are two alternative ways of measuring hate crime – one comes from a survey of victims in households (the Crime Survey for England and Wales) and the other comes from the police (police recorded crime).

Neither gives the full picture. The Crime Survey suggests a much larger number of hate crimes because there are lots of cases that never come to the attention of the police. But it doesn’t include, for example, crimes against children under 16, or crimes against society in general, rather than specific victims. Both are captured by police data.

The survey is also a limited sample of people, so the results for several years need to be combined into one number. That makes it hard to determine trends in hate crime over time from the survey.

At the same time, the police have been improving how they record crime over several years, and this can make it look like crime is rising when it isn’t, or like crime is rising faster than it is.

What we know

Between 2015/16 and 2017/18, there were an estimated 184,000 incidents of hate crime a year, according to the Crime Survey for England and Wales. That’s 40% lower than the estimated levels between 2007/08 and 2008/09.

Hate crimes represent about 3% of crimes recorded by the survey.

Only about half of hate crimes picked up this way are believed to be reported to the police.

94,000 hate crimes were recorded by the police in England and Wales in 2017/18. That’s an increase of 17% on the previous year and more than double the number five years ago.

Hate crimes represent about 2% of crimes recorded by the police.

The majority of hate crimes recorded by the police are based on race (76%).

The increase in the overall number of hate crimes mostly reflects improvements to the way that the police record crime, but is also thought to reflect genuine rises in crime.

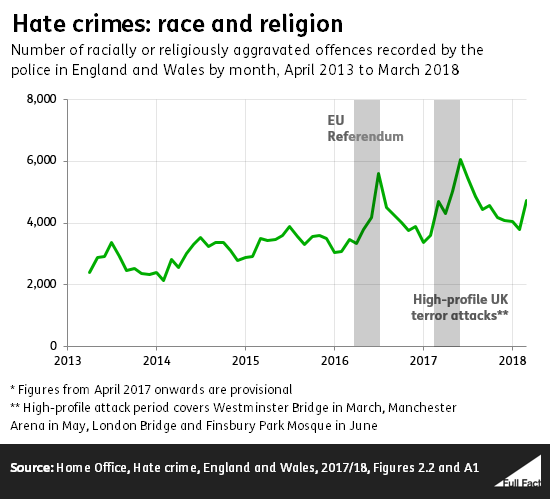

There was a “clear spike in hate crime” around the time of the EU referendum, according to the Home Office: both during the campaign and after the result was announced. Anecdotally, the Home Office also says offences related to xenophobia specifically increased around this time.

There was also a rise in the number of racially or religiously aggravated offences around the time of the referendum. These were 44% higher in the month following the referendum result compared to the same month in the previous year.

Since the referendum, there have also been spikes in recorded hate crimes following recent terror attacks in the UK including the Westminster Bridge attack and the Manchester Arena attack.

This article covers statistics in England and Wales, information on Scotland and Northern Ireland is published separately.

The definition of hate crimes is based on perception

A hate crime is defined as “any criminal offence which is perceived, by the victim or any other person, to be motivated by hostility or prejudice towards someone based on a personal characteristic.”

There are five types of hate crime that are monitored by the Home Office: those based on the victim’s perceived race, religion, sexual orientation, disability, or because they were transgender. The vast majority of these—almost 80%—involve race.

So these figures don’t cover hate crimes that fall outside of these areas—like those based on age, gender, or terrorist incidents that are seen to be targeted against general values. The government has announced a review into whether hate crime should include those based on gender and age.

Anyone can be the victim of a hate crime, and a victim doesn’t have to actually be a member of the targeted group. For example, someone who is targeted because they’re wrongly assumed to be gay would still be a victim of a hate crime.

Not all hate crimes are separate offences

The police can flag any offence as being motivated by one of the types of hate monitored by the Home Office. This is what makes up the 94,000 recorded hate crimes in 2017/18.

As well as this, some crimes have a specific racially or religiously motivated element which are treated as separate offences. These produce a different set of figures just for these offences.

The step before something is recorded as a crime is a ‘hate incident’. All reports to the police are recorded as ‘incidents’, though they’re not necessarily crimes. The police encourage people to report incidents, even if no law has been broken, to help them prevent future crimes.

Hate crimes often spike after major national or global events—although it’s not always entirely genuine

Major national and global events are sometimes followed by a spike in recorded hate crimes.

There may be several reasons for this, and we don’t know how important each one is in a specific case.

In the case of the EU referendum in 2016, there were three main factors in play:

Firstly, the actual number of hate crimes will have increased.

Secondly, people will have been more aware of possible motivations and more likely to report them to the police.

Thirdly, the police are known to have improved the way they record crimes in recent years. This means that some rises in recent years aren’t completely genuine—they happen because more crimes are being recorded, not because more are taking place.

Relatively few hate crime offences result in prosecution

One in eight hate crime offences result in a suspect being charged or a witness being summonsed to appear in court. Nearly three quarters of cases halt because of difficulties in finding evidence, identifying the suspect, or getting the victim’s support for further action.

About 14,000 hate crime prosecutions took place in 2016/17. That’s down 2% compared to the previous year.

That said, hate crimes convictions are leading to harsher sentences. When people are convicted of hate crimes the CPS can apply for what’s called an ‘uplift’ to increase the sentence. In 2017/18, two thirds of hate crimes successfully prosecuted by the CPS involved an uplift.