How overcrowded are prisons in England and Wales?

"We do not have a prison overcrowding crisis. Today's prison population is 85,359, against a total useable operational capacity of 86,421, which means we have more than 1,000 spare places across the prison estate...

"Prison overcrowding is lower under this Government than it was in the last four years of the previous Labour Government"

Chris Grayling, Justice Secretary, 16 June 2014

Over the weekend the BBC learned that already overcrowded prisons across England and Wales are being asked to take on more prisoners and raise their operating capacity.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

This prompted the Chief Inspector of Prisons, Nick Hardwick, to lament the "political and policy failure" over resources for the Prison Service, pointing out that "the demands on the system now completely outstrip the resources to meet them".

In response to questions from MPs this week, the Justice Secretary denied there is a crisis of overcrowded prisons and compared the current situation favourably to Labour's last few years in office.

While Chris Grayling's claim is correct, it doesn't necessarily prove there isn't a problem. Prisons in England and Wales overall are within 1,000 places of breaching standards of safety, although this line hasn't been crossed yet, for the most part. Situations at local establishments suggest capacity has virtually been reached or being breached.

In addition, most prisons are already overcrowded (in breach of 'good, decent' accommodation standards): there are currently 9,000 more prisoners in custody than uncrowded standards recommend - standards the Prison Service aspires to provide universally. However, this isn't purely a recent phenomenon.

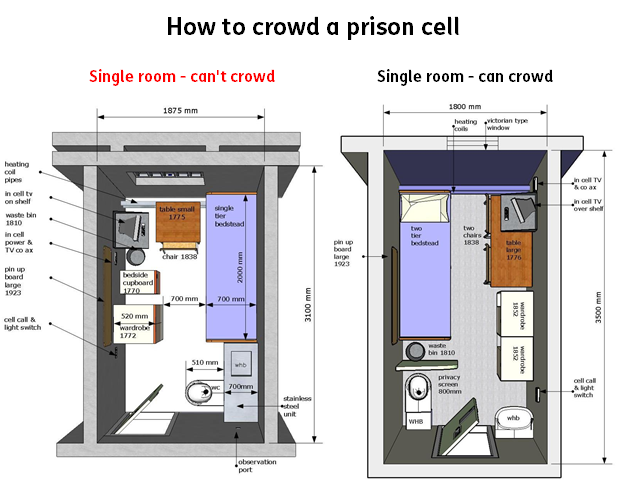

What crowded prisons look like

The Prison Service actually has two distinct measures of crowding: 'uncrowded capacity' (technically called 'certified normal accommodation') and operational capacity. According to the Ministry of Justice (MoJ), uncrowded capacity:

"represents the good, decent standard of accommodation that the Service aspires to provide all prisoners"

Meanwhile operational capacity is:

"the total number of prisoners that an establishment can hold without serious risk to good order, security and the proper running of the planned regime"

Prison Service regulations give us an idea of what this means in practice. Normal accommodation standards mean prisoners are entitled access to a bed, chair and table area, storage facilities and basic 'circulation and movement'. They must be able to use a toilet in private (at least a cubicle), and if they're in a double room the toilet should be ventilated separately. Even if there's a bunk bed, there needs to be enough space for two separate beds.

In crowded conditions - which most prisons currently have some element of - there are compromises. Storage space is reduced, toilets do not need a full cubicle and don't need to be ventilated separately. There only needs to be enough room for bunk beds rather than separate ones. Personal pursuits such as reading, writing, music and television are more restricted as well.

So while the former is a good standard, the latter is something of a red line. Operating capacities are set by the Prison Service itself based on the particular conditions of a particular prison.

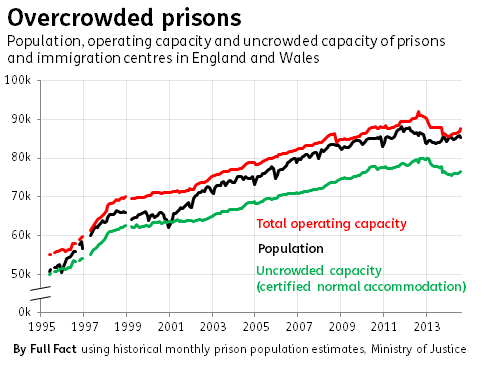

Prisons crowded but within capacity - just

For the last few years, prisons have tended to fall within operating capacity but exceed normal accommodation standards. The historical picture shows this is actually quite normal, the population has only fallen within normal accommodation standards at the end of 1995 and 2000.

The latest figures for the last week of May 2014 show that 73 out of 123 prisons and immigration centres had more prisoners than their uncrowded capacity, and three had slightly exceeded their operational capacity as well. Most had populations of at least 98% operating capacity. These numbers can fluctuate on a weekly basis.

Overall, Chris Grayling is correct that the prison population is smaller than the total capacity of prisons. But it's worth remembering this is against a maximum operating standard rather than an aspired-to standard of decent accommodation. The trends since mid-2013 also show a growing population and a falling number of places, meaning we're now close to full capacity.

Overcrowding isn't new

Some - including Shadow Justice Secretary Sadiq Khan - point to local cases of prisons full to capacity and well beyond their uncrowded standards as evidence of a 'crisis' in the system. As well, the national trends indicate the prison population is fast approaching operating limits.

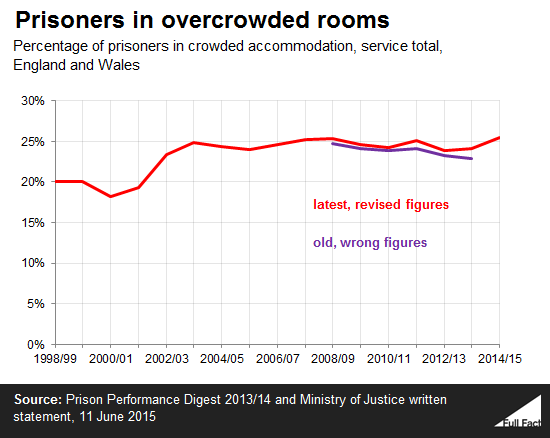

Those examples are supported by the numbers, but this isn't entirely a recent phenomenon. Prison performance statistics measure the issue differently: they count how many prisoners are in crowded accommodation. This isn't just how many more prisoners there are than the recommended standard: if there are 12 prisoners living in a room for 10, all 12 are classed as living in a crowded abode.

About a quarter of all prisoners live in 'overcrowded accommodation' (the MoJ's term). The Justice Secretary is right that the recent proportions (up to March 2013) are lower than under the last years of Labour, but the long term trend shows that overcrowding has always existed to a similar extent.

The MoJ points out that crowding isn't evenly dispersed across prisons. Male local prisons, which predominantly hold remand and short-sentenced prisoners from local courts, have the highest levels of overcrowding.

So these figures don't tell us very much about longer-term overcrowding where prisoners are spending extensive periods in substandard conditions.

Update (12 June 2015)

The Ministry of Justice recently admitted its figures on the proportion of prisoners in overcrowded accommodation underestimated the extent of overcrowding. In some cases, two prisoners living in a room with uncrowded capacity of one were only counted as one overcrowded prisoner. They're supposed to be counted as two, of course. We've added in the revised figures to our second graph.