Release from prison: how early is too early?

"Chris Huhne and Vicky Pryce should have spent longer in jail, Chris Grayling says."

Daily Mirror, 22 May 2013

"Chris Grayling to crack down on criminals freed early from jail."

Daily Telegraph, 22 May 2013 (also in Daily Mail)

Justice Secretary Chris Grayling proved this week that you don't need a speech or a press release to make headlines about upcoming policy.

In what has been judged a carefully laid hint about the Government's intent to 'toughen up' sentencing laws, the Justice Secretary responded to a recent call in Parliament from Philip Davies MP for more prisoners to serve their jail terms in full by answering:

"On this matter, I have a lot of sympathy with what my hon. Friend says. He may have sensed from my recent comments that I am looking closely at this area. I hope to be able to provide further reassurances to him in due course."

If we take this to mean that sentencing policy is about to undergo an overhaul, it's a good idea to establish exactly what the 'problem' is at the moment.

How sentencing works

Legislation tends to set out broad sentencing rules which govern how judges and magistrates decide upon sentences. A good example is the Criminal Justice Act 2003 which sets out, among other things, the rules on sentencing for murderers which Full Fact has discussed in detail before.

More detailed guidelines on specific offences are provided by the Sentencing Council. For offences committed since 6 April 2010, courts have a statutory obligation to follow the guidelines unless it is contrary to the interests of justice to do so (to allow for exceptional circumstances).

As an example, the Sentencing Council provides definitive guidelines for magistrates which assist them in delivering accurate sentences (or referral to a Crown Court if it's serious) for any offence which comes before them.

So why are people let out early?

There are essentially three types of prison sentence: suspended, determinate and indeterminate. Suspended sentences don't actually involve going to prison provided offenders comply with requirements set by the sentence, such as obeying curfews or undertaking treatment for alcohol addiction. Indeterminate sentences - including life sentences - involve a judge setting a minimum term, after which an offender can be released by a parole board on licence. The only exception is a 'whole life order' in which offenders are never released.

Determinate sentences are the most common form of prison sentence and it's these that are the focus of the 'early release' criticism. At present, if someone is sentenced to less than a year in prison, they're released at the halfway point with no further obligations, although they could have to spend the sentence at a later date if they commit a further offence.

The government wants to change this however as part of their 'rehabilitation revolution', so that these offenders will still receive a year's supervision, however short their sentence (page 13 of the Government's policy document illustrates how this will work).

People sentenced to more than 12 months in prison are also usually released at the halfway stage. However, here this doesn't mean offenders walk free, instead the remainder of the sentence is spent under supervision from the probation service. If a new offence is committed or the terms of the supervision are broken, offenders are recalled into prison to serve the remainder of their sentence, and any new sentence they might have incurred from new offences as well.

There's also an additional reduction available to some prisoners in the form of the Home Detention Curfew (HDC), (what Chris Huhne and Vicky Pryce received) which came into force in 1999. All eligible prisoners serving between 12 weeks and 4 years can be released up to 135 days before the normal half-way point. Once released, prisoners are electronically tagged to monitor their compliance with their release conditions.

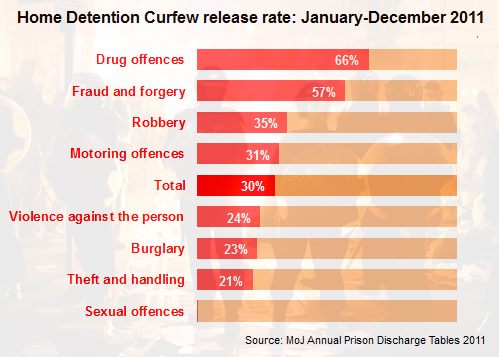

There are obviously restrictions on who's eligible for a HDC. Violent and sexual offenders serving extended sentences, for instance, are not eligible for a HDC, nor are under-18s or anyone who's previously breached a HDC condition or offended while on release from prison. Moreover, all eligible offenders have to undergo a risk assessment anyway before being released.

The graph below shows what proportion of prisoners are released on a HDC by offence:

What's happening in practice?

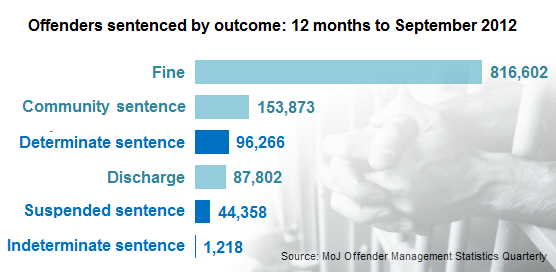

Obviously every case is different and an offender's sentence can be substantially altered by aggravating and mitigating factors unique to the offence on trial. However it is possible to get a broad picture using existing statistics.

The Ministry of Justice publish quartely offender management statistics which can trace the movement of offenders as they pass through the justice system. Prison discharge tables provide information on who's being released and how much of their sentence they served, the most recent data being available for the last quarter of 2012.

The figures show that, on average, determinate-sentence prisoners serve just over half of their sentences in custody - consistent with the general early release rules outlined above. An average on it's own doesn't tell us very much about the variance, as some offenders will be let out sooner and others may have their sentences extended for poor discipline in prison.

There is a consistent variation by gender however - men tend to serve 52-54% of their sentences while women consistently serve 46-49% of theirs. The Ministry of Justice explains why this might be the case:

"This gender difference is consistent over time, and partly reflects the higher proportion of females who are released on Home Detention Curfew."

This is borne out by statistics from the annual release tables, which show that a consistently higher proportion of women prisoners get released on a HDC - in 2011 the gap was 45% of eligible females securing early release versus 28% of eligible males.

So the avaialble figures demonstrate how 'early release' is an integral part of the current sentencing framework, and is being realised in practice. So if the Justice Secretary is indeed hinting there's going to be a change in policy, it's likely to have a substantial impact on how we're sentenced.