Are living standards on the rise?

This was the Chancellor's response after yesterday's GDP figures suggested the economy grew by 0.6% in the second quarter of this year. Yet following his comment piece in this morning's Times (£), the main point of discussion on social media seemed to focus more on George Osborne's stats than on the health of the economy. In particular, the Chancellor claimed that:

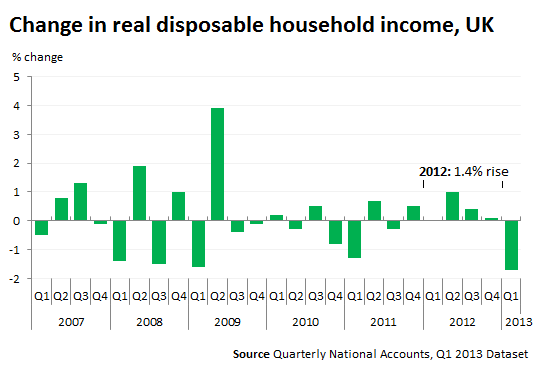

"Government policies really can make a difference to who benefits from this recovery ... disposable incomes grew by 1.4% above inflation last year despite the squeeze, the fastest for three years."

So disposable incomes (money that's left in people's wallets after taxes and regular cash transfers are taken away) are on the rise, and growing faster than inflation? Today's New Statesman claimed otherwise, saying that while this 1.4% rise did apply to last year as the Chancellor stated, this actually left out the most recent piece of data for the start of 2013, showing the reverse.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

The measure that both are talking about is called real household disposable income, which the Office for National Statistics (ONS) publish in their Quarterly National Accounts release. This is basically the total amount of money that households have available from their income, minus their taxes and charges, adjusted for inflation.

The Chancellor's 1.4% is correct as a description of what happened in 2012, and it is the fastest yearly growth since 2009. However this ignores the latest figure for the first quarter of 2013 - a 1.7% drop. It's clearly not giving readers a full picture to miss out the latest period of data that starkly contradicts the trend of 2012.

At the same time, it's too early to jump on the 2013 figure as signalling an oncoming decline in disposable income. The trend going back to 2007 demonstrates the quarterly changes can be volatile - even the downturn of 2008 didn't see consistent falls in overall disposable income.

Even then, this isn't a very good measure for living standards. The numbers for real household disposable income just give a sum total of all the disposable income in the economy during a quarter, so it could just be that any increase is simply a few thousand more households entering the economy rather than the existing households getting better or worse off.

So we need better measures.

Sadly, 'living standards' isn't something that a single number can represent. There are measures for real household disposable income per head from the Blue Book but this only gives an annual picture up to 2011 (although does show year-on-year falls since 2009).

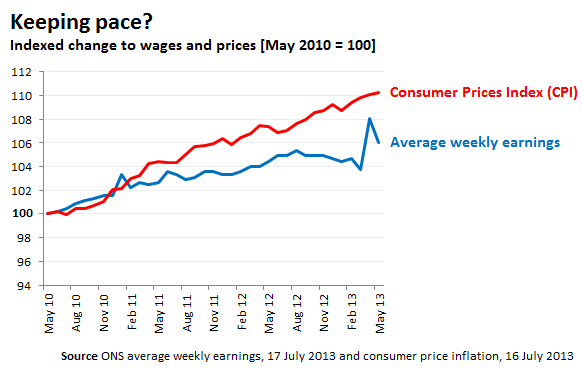

Another alternative is to compare how average wages have fared against prices.

Figures from the ONS's average weekly earnings and consumer prices index (CPI) can give some picture of how real wages have fared since the election. Average earnings per week at the election were £449 compared to £476 three years later - a rise of 6%. However prices according to CPI inflation have risen by 10%.

So in this sense, wage rises have, on average, proven less valuable as prices have been shooting up faster still.

However to give full justice to an analysis of living standards means appealing to other measures beyond wages, something which others like the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) have done in far more detail previously.

So while George Osborne's and the New Statesman's claims can be made to match the figures, we need to look further to get a fuller understanding of what's going on.