On 16 May we wrote an article saying that there has been no significant change in the level of child poverty under the Conservatives, based on official data.

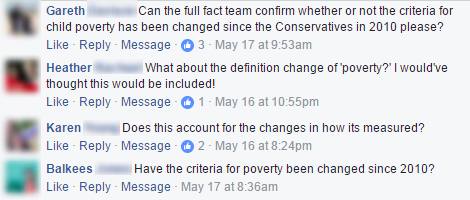

Some people asked whether this took account of government changes to the definition of poverty.

These comments are on to something. The government has started to use a different set of measures to set targets for reducing child poverty. But they haven’t changed the definition of poverty used in the official data.

We weren’t talking about those new measures in our article. We were using the measures of poverty which the original targets were based on.

If the government tried to claim that “child poverty is down” by comparing the original targets to the new ones, we’d be the first to point it out.

The government has switched its child poverty targets to a different measure

There have been a number of headlines in recent years about government plans to “redefine child poverty”.

There certainly has been a shift in the focus of government targets.

The Child Poverty Act 2010 set targets for the government to reduce child poverty, measured using two financial measures of poverty. In the statistics, ‘relative poverty’ is defined as a household earning less than 60% of the median income and ‘absolute poverty’ as earning less than 60% of the median income in 2010/11 (adjusted for inflation).

In 2016 those targets were scrapped and replaced with a duty to monitor and report on the number of children living in “workless households” and the educational performance of “disadvantaged children”.

But the statistics on relative and absolute child poverty weren’t scrapped.

The House of Lords pushed the government to keep a requirement to publish these figures in the legislation, even if the targets based on them were abandoned. It eventually agreed. So the Work and Pensions Secretary is obliged by the Welfare Reform and Work Act 2016 to publish child poverty data based on the original financial measures.

The Department for Work and Pensions said at the time that “we’ve always been very clear that we will continue to publish low-income statistics”, whether legally obliged to or not.

We compare how poverty has changed on the original measures

The upshot is that figures on relative and absolute child poverty have been published consistently since 2002, and are still available.

Despite some small methodological changes, they’re a consistent benchmark.

The changes include updating the figures to use the new measure of inflation recommended by the National Statistician.

Some people have criticised switching the targets to new measures of poverty

The decision to switch targets reflected Conservative doubts about whether purely financial measures of poverty were useful.

It’s been argued that creating those new criteria on “workless households” and “disadvantaged children” alongside the more familiar financial measure of poverty will muddy the waters. Prospect magazine editor Tom Clark has written that:

“The purpose is to cloud accountability—to create so many indicators that there is bound to be some nugget or other of good news to point to, even in a land where the poor are getting very much poorer. The objective is to whip up confusion in place of clarity.”

That’s possible. But it’s very different to the situation our readers were talking about: that the government has meddled with the existing measures in a way that means fewer children are captured as being “in poverty”. Again: those absolute and relative poverty figures are consistent over time.