Did higher taxes lead to reduced revenue from the rich?

The Daily Mail this week bemoaned Nick Clegg's recent 'wealth tax' plan, drawing upon claims from the Labour party that the Deputy Prime Minister was engaging in little more than a "cynical stunt".

Former Conservative cabinet minister John Redwood was also among the critics, warning that higher taxes on the wealthy can lead to a lower tax take for thTreasury. But one statement may have caught readers' eyes:

"The 50p rate has been very damaging and has led to a big reduction in income tax revenue from the rich. The lesson of history is that if you want to raise more revenue from the rich you need lower tax rates."

This seemed to echo a similar claim about the 50p tax rate from the Prime Minister in April, who said in Prime Minister's Questions:

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

"[The 50p] top rate of tax has not raised any money."

As we discovered, this isn't quite right. HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) published a review this year which examined the effect of the 50p additional rate of tax, and found that:

"The conclusion that can be drawn from the Self Assessment data is therefore that the underlying yield from the additional rate is much lower than originally forecast (yielding around £1 billion or less), and that it is quite possible that it could be negative."

So, while not discounting the possibility that the 50p rate lost money (because of the range of uncertainty), HMRC's central estimate was that £1.1 billion was raised by the policy. In other words, the Treasury took in £1 billion more than it would have if the old 40p rate had endured.

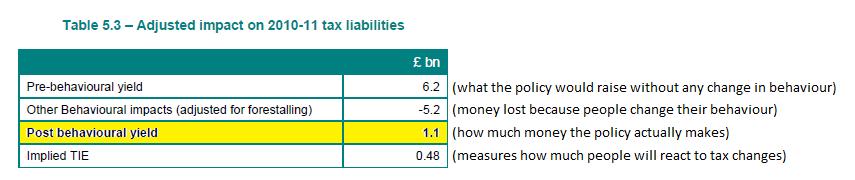

Part of John Redwood's point, in fairness, is that raising income tax produces negative 'behavioural' effects - i.e. when people affected know the tax rate is going to rise they take steps to avoid paying it. HMRC's estimates indicated that the policy would have raised as much as £6.2 billion if people didn't react at all to the changes:

[TIE = Taxable Income Elasticity, in plain English: how much people will react to a tax increase in order to reduce how much tax they will be liable to pay.]

It's also relevant to point out that the previous Government estimated the policy would raise £3.05 billion in 2011/12, so there is certainly a point to be made that the policy likely made less money than was expected when it was first introduced.

However it's still misleading to say that, in spite of HMRC's uncertainty, their estimate shows that the tax "has led to a big reduction in income tax revenue from the rich".

So what's the lesson from history?

HMRC's study, which itself draws upon a range of academic literature, helps to demonstrate how raising income tax thresholds doesn't necessarily produce a rise in revenues.

The effect of tax changes on revenue is a fraught topic and the subject of quite some debate, however we can at least look at the history of the additional tax rate to see what effect it has had on government revenues.

The previous occasion on which the highest rate was changed was in 1988, when it was decreased from 60 to 40 per cent. This cost the government just under £1 billion in 1988/89 and £2 billion in 1989/90 in revenues compared to 1987/88 (in 1988 prices). This might suggest that history shows that higher tax rates do produce marginally bigger revenues for Government.

However the Institute for Fiscal Studies, who studied tax changes taking place in the 1970s and 80s as part of the Mirrlees Review, concluded that raising the rates was unlikely to be an effective method of making the money back:

"The way that incomes have responded to the large changes in top marginal tax rates over the past 40 years suggests that if the richest 1% see a 1% fall in the proportion of each additional pound of earnings that is left after tax, then the income they report will rise by less than half that - only 0.46%... So there does not seem a powerful case for increasing the income tax rate on the very highest earners, even on redistributive grounds - it would not generate much if any extra revenue to transfer to the less well off."

So Mr Redwood could at least be excused for raising a valid concern about how effective higher rate tax rises actually are, even if the evidence that they actually don't raise any money seems scant.

The Mirrlees' review's own commentary on the matter speaks volumes:

"The Treasury's best guess is that the 50% rate will raise some revenue. That is certainly not impossible, but it certainly uncertain."