Employment, hospital beds, and A&E: factchecking Prime Minister's Questions

Join 72,547 people who trust us to check the facts

Subscribe to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Employment

"On unemployment, I'm sure the whole house will want to welcome the fact that there are half a million more people in work in our country in the last year alone. We've had wages growing above inflation every month for a year, and the claimant count is at the lowest level since 1975"—David Cameron

There were 505,000 more people working in the three months ending in October 2015 than in the same period in 2014.

Unemployment fell by 244,000 over the same period. Flows into employment don't just come from the pool of unemployed people; people can be economically inactive, or new to the population of people aged 16 and over.

It's not just the number of people in work that's been growing; pay packets have also grown consistently over this year. Year on year real wage growth was positive in each three month period in 2015.

Mr Cameron also talked about the claimant count. In November, this sat at 796,000, but that's not the lowest it's been since 1975. It's slightly higher than the figure for July (791,000). And in in February 2008, the claimant count was 778,000.

July 2015 did see the lowest claimant count rate since 1975. The claimant count rate is tricky to interpret. It measures the proportion of the workforce (unemployed and working people) that claim unemployment related benefits. It uses the number of jobs in the economy to measure the number of people in work, so the rate can change if, for example, the number of people working second jobs changes.

Hospital beds

"The number of days that people are being kept in hospital because there is nowhere safe to discharge them to has doubled since the Prime Minister took office"—Jeremy Corbyn

"The average stay in hospital has actually fallen since I became Prime Minister from five and a half days to five days."—David Cameron

The two leaders are talking about different things, both specific to the English NHS and both of which are backed up, to an extent, by the available figures.

Jeremy Corbyn is referring to the number of 'delayed days' for short-term (acute) treatment. This is where patients are fit to be discharged or transferred but there's a delay till that happens for some reason. David Cameron is talking about the overall average length of stay for people admitted to hospital.

Mr Corbyn's 'doubling' is almost there: the total number of acute delayed days is up from about 58,000 in October 2010 to over 104,000 in October this year. That excludes 'non-acute' days which tend to cover longer-term treatment. They're at similar levels to 2010 but have been rising in recent months.

There are all sorts of reasons why there might be delays and not all of them are about there being "nowhere safe to discharge them to" as the Labour leader says. Some of the delays are caused because patients' needs are still being assessed, for instance. It is true though that the main driver of recent increases in delays has been patients waiting for care arrangements in their own home or in residential and nursing homes before they can go there.

The Prime Minister is also right to say the average length of stays in hospital is falling.

At the same time this isn't unambiguously good news. It could reflect, as has been pointed out before, a change in the types of illnesses that are resulting in admissions to hospital. If minor cases that would previously have been dealt with in the community are coming into hospitals, that could shorten the average length of stay.

A&E waiting times

"Yes there are challenges in A and E, but there are 2,100 more people seen within four hours today than five years ago."—David Cameron

There were actually almost 22,000 more people 'seen' within four hours of arrival at A&E in October 2015, compared to October 2010. Here 'seen' means being discharged, transferred or being admitted to hospital.

This doesn't tell us that much about A&E performance because more people are visiting A&E. Comparing over the same time periods, the number of people waiting over 4 hours rose by 100,000.

The proportion of people being seen within four hours in October was 92%, compared to over 97% in 2010. 92% is also low compared to recent years.

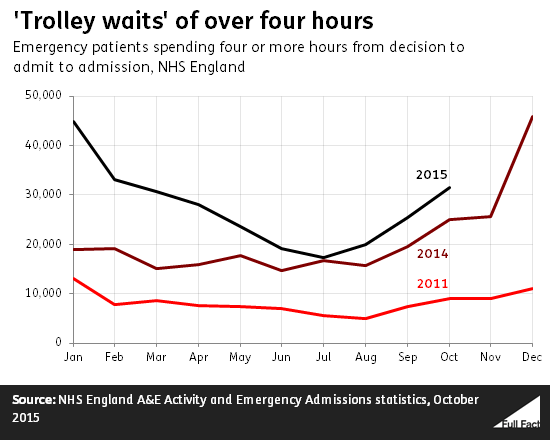

"Is it because the number of people being kept waiting on trolleys in A and E has gone up more than fourfold, that he does not want to publish those statistics?"—Jeremy Corbyn

The period between a doctor deciding to admit a patient to hospital and that patient actually getting a bed is often called a 'trolley wait' by experts. This doesn't always have to involve them literally being put on a trolley.

NHS England publishes the monthly number of patients who've waited like this for four or more hours. Starting in 2010, it used to publish the numbers who waited per week. This year it hasn't done so, although it continues to publish the monthly figures.

The latest data we have is for October this year, when 32,000 admissions were delayed for four or more hours after the decision to admit them had been made. That's more than four times the 7,000 who were delayed in 2010.

Last year there was a large rise in 'trolley waits' in December. It's too early to say whether or not that will be repeated.

These waiting times don't include the time patients wait to be seen by doctors after arriving at A&E, just the time it takes to be admitted once the decision to admit is made.

Refugees

"According to Oxfam, the UK has donated a generous 229% of its fair share of aid in support of Syrian refugees - the highest percentage of the G8. Yet worldwide only 44% of what is needed by those refugees has been donated."—Fiona Bruce MP

Oxfam did reach the conclusion that the UK had donated 229% of its 'fair share' of financial assistance to the Syria crisis. The UK's percentage was the highest of the G8 countries.

The analysis looks at around 30 countries, and calculated country's' 'fair shares' roughly based on the size of their economies. Oxfam estimated that total need for the Syria crisis came to $8.9 billion. They reached this figure by adding combined UN appeals to those by the Red Cross and Red Crescent societies. It's not clear if this would mean some needs are double counted. We've asked Oxfam to clarify.

It estimated that 44% of that $8.9 billion had been received. We've also asked Oxfam if this includes the money pledged.