Homelessness in England

There’s a legal duty for the state to help people who are homeless or threatened with homelessness. Councils are responsible for this in England, Wales and Scotland, while Northern Ireland has a single organisation responsible for housing.

Each country has a slightly different approach, but in general the authorities must find somewhere for a person to live if: they meet the immigration status requirements, are accepted as homeless, are in a ‘priority need’ category (except in Scotland), and haven’t become homeless intentionally (optional for councils in Wales).

Claims about homelessness often refer just to England, rather than the whole of the UK. We've focused on that here, although there are separate figures for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

What 'homelessness' means in England

Not everyone who becomes homeless is entitled to be housed.

In England councils only have a duty to find somewhere for a person to live if they have a ‘priority need’. This includes families with children, people in an emergency after a flood or fire, or who are “vulnerable” for various other reasons. In addition, they must not have deliberately done or failed to do anything that caused them to become homeless.

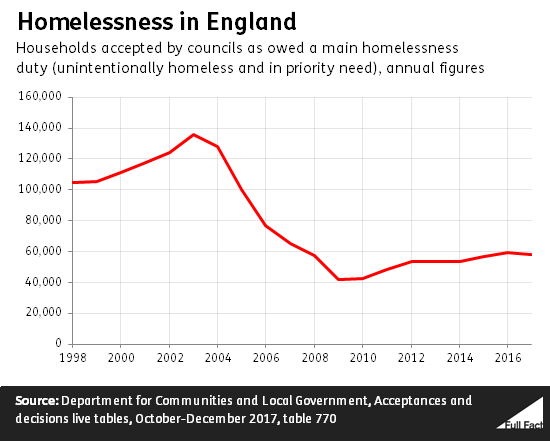

Around 59,000 households were accepted by councils as entitled to be housed in 2016/17. This number has been rising since 2009/10, and is up by almost 50% over that period.

However, it’s 56% below the level of 2003/04, when 135,000 households were accepted.

These figures don’t include those who were assessed as homeless but not in priority need, or homeless but intentionally so.

There are around 20,000 cases found homeless but not considered in priority need each year, or around one in six of all decisions. Around 9% of cases, or 10,000 households, are homeless and in need but considered to be intentionally so.

If councils decide someone is not in priority need they have to offer advice and help with finding somewhere to live, but not accommodation. If they decide someone is intentionally homeless and in priority need, they only have to provide short-term accommodation.

The law is changing

A new law – the Homelessness Reduction Act 2017— is set to come into force in April this year.

Amongst other things it put new duties on local authorities in England to prevent and relieve homelessness for everyone, including people who don’t count as ‘priority need’.

The government has promised £73 million to local authorities to meet the new requirements. A new code of guidance for local authorities has been published as well.

Temporary accommodation

People can be put in temporary accommodation while their claim is investigated or they are waiting for somewhere suitable. Temporary accommodation can include B&Bs, hostels, council housing and private rentals.

In England 64% of households who accepted an offer of housing in the last three months of 2017 were given temporary accommodation. 86% of households in temporary accommodation on December 31st were placed in “self-contained accommodation”, such as council or private rentals. The rest were in B&B or hostel-style accommodation.

69% of English households in temporary accommodation were in London.

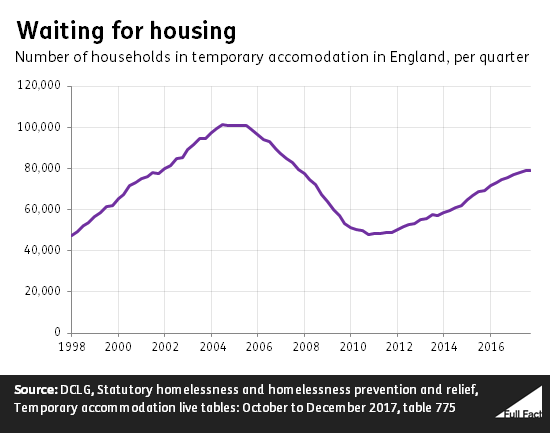

At the end of 2017, 79,000 households were in temporary accommodation. This is 4% higher than the same time in 2016. The number has been increasing steadily since 2011, but is still well under the peak of 101,000 in 2004.

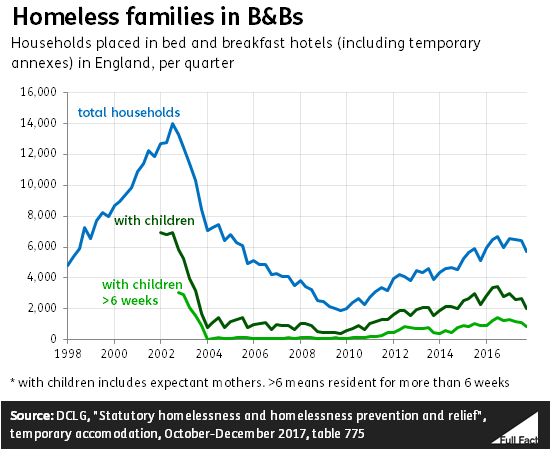

Around one in 14 households in temporary accommodation were in bed and breakfasts in the last three months of 2017. Governments have been concerned about families with children being placed in B&Bs since the early 2000s. Since April 2004, the law has said that families with children should not be housed in B&Bs except in an emergency, and then only for six weeks.

2,030 families with children were in B&Bs in the last three months of 2017. This has been increasing since 2011, but is below the peak of 7,000 in 2002.

Rough sleeping

People who are legally homeless are “rarely” on the streets, according to the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. We don’t have definitive statistics for how many people are sleeping rough.

In England the number of people sleeping rough is a snapshot taken in autumn each year. Councils count or estimate the number of people sleeping rough in their area. Most authorities talk to local agencies and give an estimate.

So the figures we’re using here are only very rough estimates.

Last year, around 4,800 people were estimated to be sleeping rough in England. This is 15% higher than in 2016, and more than double the estimate of 1,800 for 2010.

The government started asking local authorities to count rough sleepers in the 1990s but the data before 2010 is not comparable with more recent figures. Most local authorities did not provide any numbers in the older data, and the government accepted that the data did not provide a comprehensive picture, according to the House of Commons Library.

In 2005 the government stated that rough sleeping had fallen by 75% since 1998, and in 2010 it said that rough sleeping was at an 11 year low.

But these estimates are based on a relatively small sample of local authorities and they cannot be used to put an overall figure on the number of people sleeping rough in that period.

In London a much more detailed database is kept. CHAIN (Combined Homelessness and Information Network) records people found sleeping rough by outreach teams. It’s a database funded by the Mayor of London and run by the charity St Mungo’s.

8,100 people were seen sleeping rough at some point in 2016/17, slightly more than in the previous year. Quarterly reports are also available for different areas of London.

A parliamentary committee investigating homelessness has recommended that a system like CHAIN be used in more areas.

Homelessness in the rest of the UK

In Scotland, local authorities have a duty to find accommodation for all people who are unintentionally homeless or threatened with homelessness.

Over 28,000 people were assessed as homeless in 2016/17. This was the lowest since the data began in 2002/03. In the six months to September 2017 around 15,000 were assessed as homeless.

Nearly 11,000 households were in temporary accommodation in September 2017—the highest at that time of year since 2011. 3,400 of these were families with children, an increase of 3% on the previous year.

Welsh local authorities are required to prevent people from becoming homeless, and to provide all applicants accommodation for 56 days. After this period, they have to help secure accommodation for people who are unintentionally homeless and in priority need.

In 2016/17 9,200 people were given help to prevent them from becoming homeless. And nearly 11,000 were eligible for help to secure a home. There were just over 2,000 households in temporary accommodation in the third quarter of 2017. Nearly 900 of these were families with children.

Northern Ireland’s local authorities, like those in England, are required to secure accommodation for people who are homeless or threatened with homelessness, and are in priority need. In 2016/17, around 10,000 people were accepted as homeless. That’s a 27% increase on the previous year.