The NHS, the military covenant and adoptions: factchecking Prime Minister's Questions

"Since I became Prime Minister, the number of doctors up by 10 and a half thousand, the number of nurses up by 5,800"—David Cameron

We're struggling to get to these exact numbers, and have asked Number 10 if it can help. The numbers are up by some thousands, whichever way you look at it.

The number of nurses, midwives, and health visitors in England went up by 6,600 between May 2010 and May 2015. These are "full-time equivalent" numbers—the equivalent of the number of full-time positions currently filled, even if the hours are shared among part-time staff. This gives us a better idea of the level of staffing by accounting for how many hours are worked.

It's trickier to get a definitive figure for the number of doctors because numbers for GPs and hospital doctors are published separately.

Information on GP numbers is annual; it's counted in September. There were just under 1,700 more in September 2014 than in September 2010. The equivalent figure for hospital doctors is 6,700, bringing the total rise to about 8,300 between those two points in time.

If you wanted to look at hospital doctors only, you could go from May 2010 to May 2015 and get a rise of 8,600. We wouldn't recommend comparing May 2010 to the most recent figures, for July 2015, however. The number of doctors always rises in July, so that comparison would include a substantial and misleading "seasonal effect". It would produce a figure of just over 10,000.

The above figures include locums, registrars and retainers and also use the "full-time equivalent" measure.

"[Since I became Prime Minister there are] fewer patients waiting more than 52 weeks to start treatment than under Labour [...] we've seen mixed wards virtually abolished, and we've seen cases of MRSA infection come plummeting down."—David Cameron

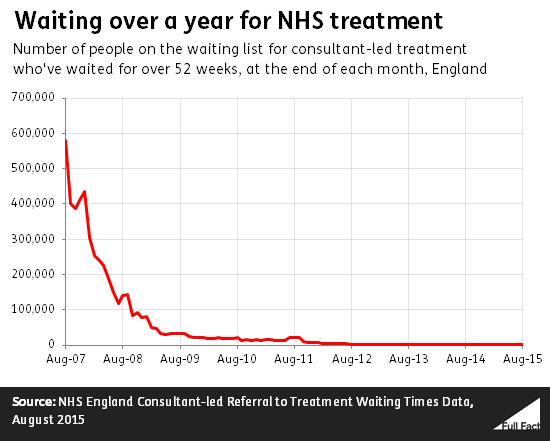

The Prime Minister is right to say waits of a year or more are far less common than when he came into office. In May 2010, over 18,000 NHS patients had been waiting a year or more for treatment (after being referred for it by their GPs). By this May that had fallen to about 600 patients.

The fall was even more dramatic in the years before his election. Our figures on this go back to August 2007, and that month there were well over half a million patients in the same position.

It's a similar story for MRSA, a difficult-to-treat bacterial infection which particularly affects people in hospital. In the 2007/08 financial year there were 4,500 reported cases. That fell to 1,900 cases the year before Mr Cameron took office (2009/10) and has continued to fall, with 800 cases reported last year.

We don't know how many patients were treated on mixed-sex wards before the 2010 election, because data only started being collected in December 2010. In November 2010 the Department of Health issued guidance calling for hospitals to eliminate the practice.

In December 2014 there were 400 cases of patients sleeping on mixed-sex wards when it wasn't "justified" by the interests of the patient. That was down from 11,800 cases in December 2010, although NHS England says this figure "should be treated with a degree of caution" because the procedures for collecting the data were still new.

Admitting a patient to a mixed sex ward can still be considered as justified, for instance if a patient needed immediate treatment for a life-threatening emergency. That wouldn't be counted in these figures.

"Since [David Cameron] took office in 2010, the English waiting list is up by a third. There are now 3.5 million people waiting for treatment in the NHS […] the NHS is in a problem. It's in a problem of deficits in many hospitals, it's in a problem of waiting lists, it's in a problem of the financial crisis"—Jeremy Corbyn

It's fair to say that hospitals are not in good financial health.

NHS trusts in England, which run hospitals as well as some other services like ambulances, had a shortfall of £830 million last financial year according to the two bodies that oversee them.

The trusts would have had a bigger deficit, had NHS England and the Department of Health (DH) not put in some £350 million in extra funding over the course of the year. DH says the "underlying" deficit for providers was £1.2 billion.

The deficit is expected to be even higher this year, with some forecasting a total deficit for trusts of £2 billion or more.

Mr Corbyn is also right to say that the waiting list has risen. At the end of August NHS England knew of 3.3 million patients who were waiting for treatment after being referred by their GP. Some trusts hadn't submitted any data for the month, but based on the last figures it had received from them NHS England thinks the true number may have been "just over 3.5 million patients".

But the size of the waiting list alone doesn't tell us very much about how quickly hospitals are treating patients. The waiting list will grow longer if patients have to wait longer (which they do, on average), but it will also get bigger if there are more patients needing to be treated (which there are).

"Those who suffer from mental ill health do not have the same right to access treatment as others enjoy in our NHS."—Norman Lamb MP

"We set out in the NHS constitution parity between mental and physical health and we've taken steps towards that by for instance introducing for the first time waiting times and proper targets for talking therapies"—David Cameron

The Coalition government added a line to the NHS constitution to say that "the service is designed to improve, prevent, diagnose and treat both physical and mental health problems with equal regard".

It also included equal priority for mental and physical health conditions in its annual lists of government objectives ("the Mandate") which NHS England has a legal duty to act on.

That duty starts at the top of the health system. But in many cases, actions from the top—such as new targets for some services—will take a while to feed through to front-line services.

The last government also introduced the first set of waiting time standards specifically for mental health, although a wider 18-week target for treatment of all conditions would have applied to some mental health patients before this (if the treatment was led by a consultant).

One of the targets says that patients with depression and/or anxiety disorders should get treatment within six weeks, usually talking therapy. The target is that 75% of patients should be seen by then, with 95% being treated within 18 weeks.

The other target is for treatment within two weeks for more than 50% of people experiencing a first episode of psychosis.

Performance against targets for therapy doesn't tell us that much about how access compares to that for physical health conditions. Analysis by the Health Foundation and Nuffield Trust think tanks suggests outpatient waiting times are worse for mental health patients, and the gap widened last year.

Some people suffering from mental ill health were also more likely to have an emergency admission than a planned admission (one where they were given an appointment in advance). And the analysis points to concerns that people are being prescribed medication where that might not be the best treatment for them.

"This is the first government to put the military covenant properly into law"—David Cameron

It's easy to think that when a policy appears in legislation—"enshrined in law", as the governments often puts it—that the law can help you enforce it. But you can't go to court on something like the armed forces covenant.

This document, also described as the Military Covenant, expresses a "moral obligation" to past and present members of the armed forces and their families.

It says they should "face no disadvantage" compared to civilians, and should get "special treatment" in some circumstances, going on give more detailed promises about various services and benefits.

The previous government said that "the armed forces covenant itself is not a legal document but its key principles have been enshrined in law in the Armed Forces Act 2011".

That's true, but as the House of Commons Library puts it, "this does not mean that it has created legally enforceable rights for Service personnel".

The Armed Forces Act 2011 says that a minister has to prepare a report for Parliament on how the government is doing on the covenant. It doesn't say that soldiers or bereaved family members have a legal right to anything that's in the covenant that they could rely on in court.

It would be unlawful for the government not to prepare its report on the covenant. But it would not be unlawful for that report to say that, for example, the government isn't keeping its promise to give ex-service personnel "priority treatment" in certain circumstances.

Any repercussions from a failure to uphold the covenant are therefore political, not legal.

"[Jeremy Corbyn] has been completely consistent; he's opposed every single reform to welfare that has ever come forward. If we'd listened to him, you'd still have families in London getting £100,000 a year in housing benefit"—David Cameron

It's been a while since we last looked at people claiming claiming six figures in housing benefit—almost exactly 3 years.

Back then, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) told us that around 120 housing benefit recipients were getting more than £1,000 a week in September 2010.

While this does put an upper limit on the number of recipients that could possibly have claimed £100,000 a year, it seems unlikely that all 120 recipients would have claimed more the £1,923 a week that would add up to the six figure sum.

We do have one figure for people claiming that amount. In 2010, a fledgling Full Fact put in a Freedom of Information request to the DWP, asking how many people were claiming more than £100,000 a year in housing benefit.

The DWP told us that in August 2010, there were "fewer than 5" recipients getting over £1,916 a week—which would be a little under £400 shy of the £100,000 per year mark, if the recipients had claimed that level continuously through the year.

"We have seen a 72% increase in the number of children adopted. The average waiting time has come down something like five months, but it's still far too long"—David Cameron

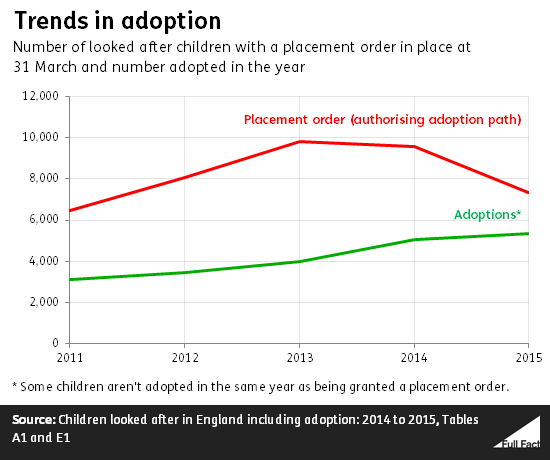

The number of looked after children adopted is indeed up 72% in England, from 3,100 in the 2010/11 financial year to 5,330 last year.

But as we noted last month, this increase may not be sustained in future. There has been a decline recently in the number of 'placement orders' granted (enabling children to live with potential adopters).

Placement orders happen at an earlier stage in the adoption process—so a drop-off in those numbers may start to feed into the number of final adoption orders in the coming months and years. We discuss possible reasons for the fall in placement orders in this factcheck.

The average length of time between a child entering the care system and being adopted is down four months, rather than five, between 2011 and 2015. The Coalition government had set out to reduce this "delay".