The UK has posted record export figures, but that’s not very remarkable

In August the UK government launched its new export strategy and the Department for International Trade made a number of claims about the UK’s recent export performance.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Records aren’t always remarkable

“Last year £620 billion of goods and services exported by British companies accounted for 30% of our GDP, with UK exports at a record high”.

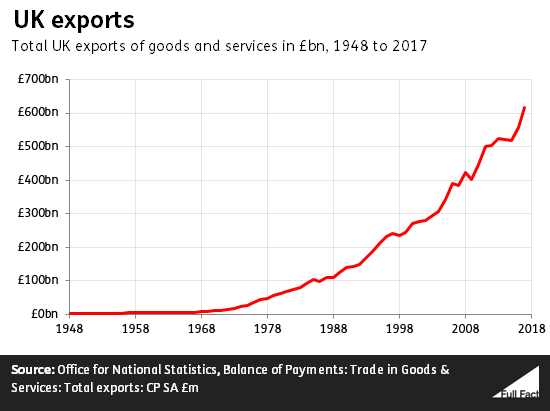

The total goods and services exports figure is broadly correct. Figures released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show that, in the 12 months ending June 2018, UK goods and service exports were worth £621 billion. That’s a record high looking back to the early 1990s—as far back as the figures ending in June each year go.

To look back further we need to compare the figures for each calendar year.

The figure for the 2017 calendar year is slightly lower, at £616 billion. This represented about 30% of estimated GDP for the same period.

2017’s figure showed 11% growth on the previous year, and was the highest figure in a series going back to 1948. But how remarkable is this?

As the graph below shows, there are only eight years in the last 69 where UK exports weren’t at a record high. Exports have grown in the vast majority of years that the ONS has records for. The only two consecutive years where they were not the “highest ever” were 2014 and 2015.

Exports have grown in the vast majority of years that the ONS has records for. The only two consecutive years where they were not the “highest ever” were 2014 and 2015.

The UK is a large global exporter, but so are most other large economies

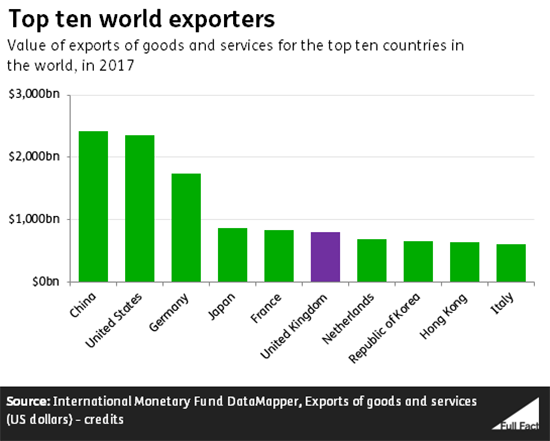

“As the world’s sixth largest exporter, we do punch above our weight, however, we also punch below our potential.”

The claim about the UK being the “sixth largest exporter” is correct and is based on 2017 data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

IMF GDP data suggests that in 2017 the UK was the fifth largest economy, roughly the same position as it’s in for exports, while another measure puts it at ninth.

We’ve asked the Department for International Trade for more information on what it meant by saying the UK was “punching above its weight” as an exporter.

More exports are going outside of the EU: but the EU will remain a key market

The UK government’s new export strategy highlights the opportunities for increasing exports to countries outside of the European Union, and claims:

“Approximately 90% of global economic growth in the next 10 to 15 years is expected to be generated outside the EU.”

The Department for International Trade told us it calculated this based on figures from the International Monetary Fund. We’ve asked the Department for more information about this calculation, but it seems to be in the right ballpark.

Back in 2015 the European Commission estimated that by 2020, 90% of economic growth would take place outside of the EU.

We covered the relative economic growth of EU and non-EU countries in a previous fact check. In short, the EU economy has grown in size, but the rest of the world economy has grown faster.

The share of the UK's exports going to the EU has fallen, from 55% in 1999 to 44% in 2017. Most of the drop in the EU’s share of UK exports is due to declining goods exports, not services.

You can see who the UK trades with, and how this has changed over time, using a handy tool on the ONS website.

The ONS says that “UK trade relationships are usually stronger with neighbouring countries, as well as countries with large economies. China and the US are large economies and important UK trading partners, even accounting for their distance from us.” But distance still has an impact. The ONS also explains that although Ireland’s economy is smaller than Spain’s or Italy’s, the UK does more trade with Ireland as it is closer.

Exports aren’t everything

The Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) has argued that people focus too much on export figures. One of the many misconceptions about trade, according to the IFS, is that “exports are good and imports bad”. In fact:

“The reverse is the case. Exports are useful because we need the money to pay for the imports we want. There is no intrinsic benefit in spending our time producing stuff for other people.”

What do we think of when we think of exports? It’s possible that the image that comes to mind is of a foreign consumer buying a British good—like a Rolls Royce—or buying a service from a British firm—like hiring a British architect.

However, lots of trade nowadays is in unfinished products within companies or to other companies, rather than to the end consumer. For example, a multinational car manufacturer exporting engine parts from one of its factories in the UK to another in Germany.

The IFS has estimated that the majority of UK exports and imports are now made up of goods or services that are themselves inputs into production elsewhere. It says that “this pattern of interdependence is crucial for understanding trade policy”.

--

Robin Wilkinson is a Senior Research Officer from the National Assembly for Wales Research Service, on secondment with Full Fact