What is unemployment?

Join 73,000 newsletter subscribers who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Q. What is unemployment?

A. To be classed as unemployed you have to be out of work and actively seeking work.

If you are not in work and don’t want to be in work, maybe because you are retired or because you are looking after a child or loved one, you don’t count as unemployed.

The official definition of “unemployed” is someone who is not in work, has looked for work in the last four weeks and is ready to start work in the next two weeks. It also includes people who are out of work, but have found a job and are waiting to start it in the next two weeks.

Q. How is unemployment measured in the UK?

A. Unemployment is measured by a survey of 100,000 adults aged 16 and over in 40,000 households in the UK. The survey uses a random sample of addresses.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) then uses the survey results to estimate the total number of people who are unemployed across the UK.

This is separate to the claimant count which measures the number of people claiming benefits because they are out of work. It includes people who are on Jobseeker's Allowance and people who are claiming Universal Credit and required to look for work.

Q. How many people are unemployed in the UK?

A. 1.4 million adults were unemployed in the UK between May and July 2018 (the latest figure).

The UK claimant count was 918,800 in August 2018. This is much lower than the number of unemployed people because the claimant count does not specifically measure unemployment. It excludes people who do not claim unemployment benefits, even if they are looking for work. It may also include a small number of people who are actually in work: for example, people who may work a very small number of hours on a low wage and who are seeking full-time work and so qualify for unemployment benefits.

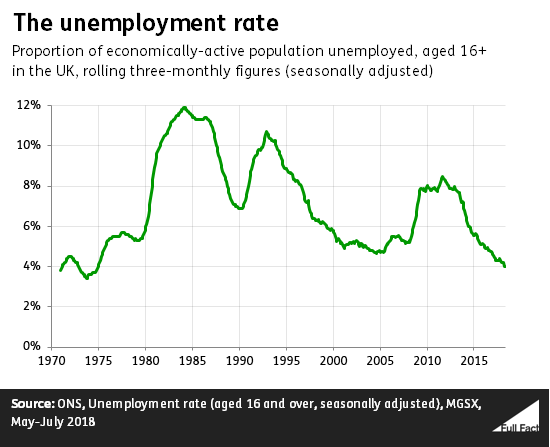

Q. What is the unemployment rate?

A. The unemployment rate is the number of unemployed people as a percentage of all ‘economically active’ people. ‘Economically active’ is statistical speak for people who are either in work or who want to be.

It counts people who are employed plus those who are unemployed and looking for work. The rate is calculated this way because statisticians are trying to count how many people who want a job don’t have one, not just how many people are not in work.

4% of people aged 16 and over were unemployed from May to July 2018—that’s around one in every 25 people who want to work. This is down from 4.3% a year earlier and the lowest it has been since 1975.

A. This is the unemployment rate specifically for people aged 16 to 24. It includes people who are looking for work and people who are still in full-time education looking for a part-time job. The ONS says it is “It is a common misconception that all people in full-time education are classified as economically inactive.”

488,000 young people were unemployed from May to July 2018 (including 168,000 full-time students looking for part-time work). This means the unemployment rate for 16 to 24 year olds was 11.3%. This figure is lower than at the same time a year earlier (11.9%) and is the lowest it has been since comparable records began in 1992.

Q. What is structural unemployment?

A. Structural unemployment is unemployment based on significant changes to the environment businesses work in—for example a change in technology, or government policy—rather than just the ups and downs of the economy.

For example it could be caused by technology changing more quickly than people can learn the skills they need for new industries. As a result, some people become unemployed or struggle to find work because fewer jobs require the skills they have. For example, think of how quickly personal computers have made typewriting jobs redundant.

Q.What is cyclical unemployment?

A. Cyclical unemployment is related to the health of the economy. When the economy is not doing well businesses lose money and lay off people to try and reduce their costs. And so unemployment goes up.

When the economy recovers businesses hire more people to keep up with increased demand for their products and services. And so unemployment goes down.

Correction 14 December 2017

We previously said the Labour Force Survey asks a carefully selected group of people for its sample. This was incorrect, and we've now made clear it uses a random sample.