Will Labour's spending plans add £500 billion to the national debt?

"Under [Labour's] plans, debt would be £500 billion higher in 21 years' time."

Sajid Javid, Culture Secretary, Daily Telegraph, 6 August 2014

"These numbers have been totally made up" was the reaction of Chris Leslie MP to the Culture Secretary's attack on Labour's spending commitments this week.

Sajid Javid's figures come from the Treasury and are based on the department's own projections for the UK's public debt under a series of different 'scenarios' based on the choice of government policy. The £500 billion is the difference between two such scenarios, one of which relates to the Conservatives' spending 'plans' and another which the Culture Secretary claims is essentially what Labour intends to do in government.

Labour hasn't set out plans specific enough to make this assumption, and could pursue policies which result in a lower or higher debt. The Conservatives' plans are similarly unspecific, and either party's long-term plans could be altered by a future administration.

There's also doubt surrounding the future impact of any policy, as the assumptions by the Treasury have to navigate a minefield of uncertainties - such as recessions - in order to project numbers so far into the future.

Join 73,000 newsletter subscribers who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

The £500 billion figure is highly speculative as a result.

Treasury scenarios for debt

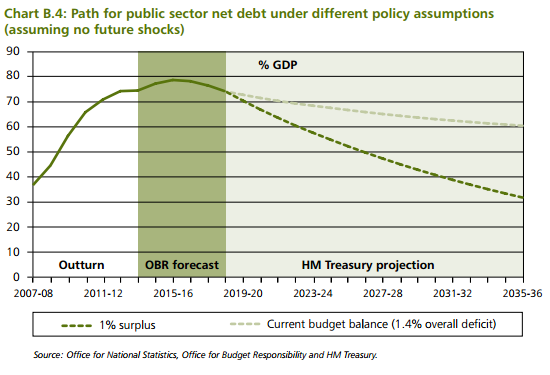

Back in April as part of the 2014 Budget the Treasury set out a series of projections of what could happen to the public debt from 2018 to 2036. It took two different scenarios:

1. There is a budget surplus of 1% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (in today's money this would be in the region of £15 billion) every year

2. There is a current budget balance (where spending is equal to income, not counting investment spending for the future) but a 1.4% overall deficit (because investment spending still sends the accounts into the red). This still leads to a falling debt as a ratio of GDP since GDP overall is expected to rise faster

[caption id="attachment_34584" align="alignnone" width="550"]

The 1% surplus scenario is based on what the Conservatives claim their plans involve. The Chancellor set out in the 2014 Budget that "Britain needs to run a budget surplus in good years" although it's not clear how much of a surplus this would be in practice. The Conservatives claim the second scenario represents Labour's plans. The difference between those two lines at the end of the period is the difference between debt ending up at either 61% of GDP or 32% of GDP - in today's money that's about £500 billion.

Labour's plans not necessarily the same

Back in January the Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls set out the fiscal commitments of a Labour government post-2015. He said:

"The next Labour government will balance the books and deliver a surplus on the current budget and falling national debt in the next Parliament."

This was picked up at the time as much for what it didn't say as what it did. Labour committed to "no more borrowing for day-to-day spending" - in other words, to balance the current budget, which excludes capital spending (investment spending). The wording was seen to free a Labour government from actually balancing the overall budget, including investments as well.

That's why the Conservatives assume Labour's 'debt line' follows the higher one in the chart: the day-to-day budget is balanced but investment spending means there's still a slight deficit overall, although debt still falls gradually as a proportion of GDP.

Since Labour hasn't spelled out what its capital spending would look like, the Conservatives take the expected levels of spending in 2018-19 based on current plans, which the Office for Budget Responsibility forecasts as 1.4% of GDP that year. The party assumes that level of investment stays the same for another two decades to reach the £500 billion claim.

This assumption is obviously very speculative. If either of the parties' actual plans differ then the figures will be different, and similarly any future administration could alter the public finances as well.

There's also the uncertainty around shocks to the economy. Recessions happen, on average, once every eight years according to the Treasury, and increase public debt by 10% on average. But these aren't evenly-spaced and, obviously, can't be anticipated. Shocks would affect both debt lines in the chart in the same way, but this still means the resulting debt after twenty years could easily be very different from the £500 billion claimed.

Another issue with the Conservatives' claim is that the Shadow Chancellor said he aimed for a "surplus on the current budget", not merely a never-changing balance for 21 years. The more of a surplus Labour actually delivers, the lower debt is likely to be in the long-term, and vice-versa.

All this depends on interpretation of Labour's claims, and - as we discussed at the time - there are several aspects which are vague. For instance, Labour's commitment to a falling debt could mean a falling debt as a proportion of GDP, or it could simply refer to it in cash terms. This makes the likely course of Labour's capital spending more uncertain still.

Image credit: Peter Gerdes