From the classroom to a job: what are the options for young people?

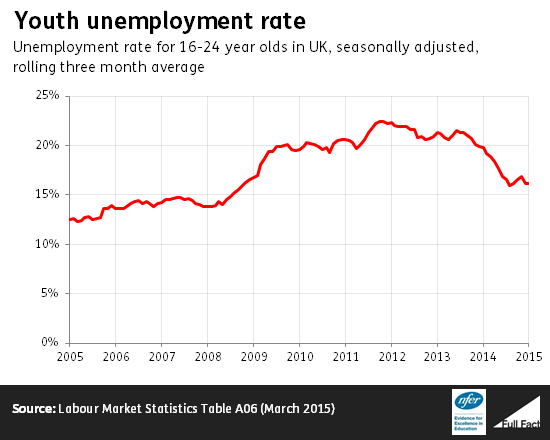

- Approximately one in six young people are unemployed (16.1%) in contrast to an overall unemployment rate of 5.6%.

- The Coalition has introduced considerable reforms of 14-19 vocational routes to employment to try and address youth unemployment and a suggested skills deficit. Although some evidence is available on the individual components, it's still too early to know what the overall effect of the reforms will be. The youth unemployment rate has been falling but this is the case for all age groups, broadly due to the economic recovery.

- Research from Ofsted suggests there's still more to be done to get effective careers education and guidance in schools and to get employers helping with the development of employability skills among young people. Research by McKinsey suggests young people feel academic education is still valued more by society than vocational training.

What reforms have taken place?

Rules introduced by the previous Labour government and implemented by the Coalition mean that all young people now have to stay in education or training until the year of their 17th birthday and from September 2015, until their 18th birthday.

One of the four ambitions of the government's 2011 Plan for Growth was "to create a more educated workforce that is the most flexible in Europe". In the same year, the Wolf Review of Vocational Education estimated that at least 350,000 young people derived little benefit from the post-16 education system. The report recommended a prioritization of vocational education through apprenticeships; genuine work experience opportunities for 16-18 year olds who are enrolled as full-time students; and a change in 16 to 19 funding.

Recommendations from the Review have largely been implemented or are in the process of being implemented, including:

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

- Changes to 16 to 19 funding from September 2013, allocating funding per student rather than per qualification. Previously, the per qualification funding meant that a young person undertaking a large number of small qualifications would attract high levels of funding for the provider. The new system removes the incentive for providers "to enter students for easier qualifications", according to the government.

- Redesigning apprenticeships with more employer input.

- Requiring young people who have not achieved an A*-C GCSE in English and maths by the age of 16 to continue studying these subjects as part of their 16-19 education.

- Introducing Study Programmes for all 16 to 19 students.

- Reducing the number of approved technical and vocational qualifications that count towards performance tables.

The Coalition has also reformed the way that career guidance is delivered. It introduced the duty for schools to secure independent and impartial careers guidance (instead of the local authority careers service) for all Year 9 to Year 13 pupils (ages 13—18) in September 2012 (extended to included Year 8 pupils in September 2013). Ofsted has reported that this is proving difficult for schools to manage and has said schools needed more explicit guidance to make this work. A study by The Sutton Trust also said that a lack of guidance, support and funding for the new responsibility has resulted in a decline in the quality and quantity of careers provision.

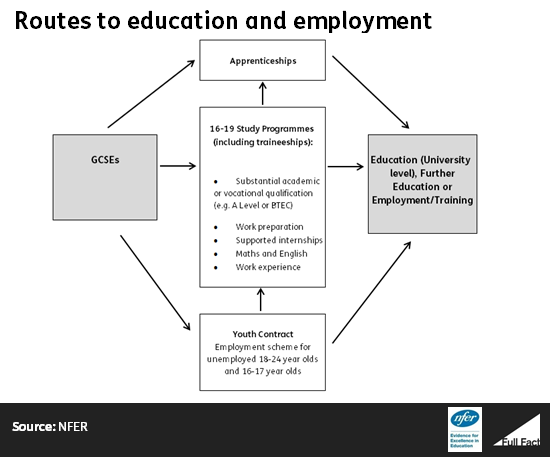

The expectation for Study Programmes is that all learners in full- or part-time education aged 16 to 19 undertake a "challenging individualized learning programme" including a substantial academic or vocational qualification; appropriate work experience; and continuation of English and maths where they do not hold a GCSE graded A*-C in that subject.

But early inspections from Ofsted found "little evidence of the transformational 'step change' intended" by the programme despite the programmes being welcomed by many providers. It found too many of the providers surveyed were not yet offering programmes that met the key requirements, and recommended the Department for Education ensures providers are more aware of the requirements and put reliable systems in place to monitor learners' progression.

Traineeships were introduced as a form of Study Programme in 2014 for 16 to 24 year olds not currently in a job, with little work experience and qualified to the equivalent of GCSE level. They are delivered over a six-month period by colleges or training organisations alongside employers and aim to secure progression to an apprenticeship or a sustainable job. There's mixed evidence as to how well they're working.

Ofsted has said that the proportion of the first traineeship cohorts moving on to an apprenticeship or employment with training was too low. Research by the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills found that, of the sample looked at, two-thirds of trainees who had left or completed traineeships were either on an apprenticeship, in work, or in further education or training. However, an Education Select Committee report suggested that greater clarity is needed over the purpose of traineeships and their success criteria.

There are two alternatives to a Study Programme:

- The Youth Contract offers employers £2,275 to provide a six-month employment programme to 18 to 24 year olds who had been unemployed for six months or longer. It also includes a strand of intensive support to 16 and 17 year olds who are not in education, employment or training (NEET). An evaluation of this strand found some positive impacts on young people's levels of engagement and participation as a result of the programme, typically through a key worker providing mentoring and advocacy to the young person. The programme operates until March 2015 (though contracts will run until March 2016).

- An apprenticeship which is a paid position that combines the practical training of a job with study. The proportion of young people taking up any kind of apprenticeship remains low, with the greatest increases under this government seen in the 25 and over age group. Full Fact has covered more detail on the trends in a separate briefing.

However, take-up of these vocational routes depends on the perceptions of them among young people, teachers and parents. Young people say that they feel vocational training is still valued less than academic education, according to a report by management consultancy McKinsey in 2014.

The youth unemployment rate has been decreasing

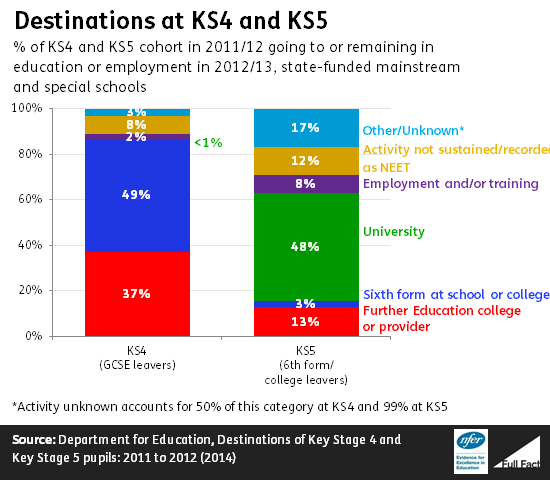

Latest available figures indicate that there's still a significant minority of young people leaving Key Stages 4 and 5 that are either not accounted for or are NEET.

The youth unemployment rate (which includes young people in education seeking part-time work) has broadly been falling since it peaked in late 2011 at 22.5%, but this reflects similar trends in other age groups and is associated with the economic recovery.

We don't know as yet whether extending the participation age to 18 will have any effect on improving young people's job prospects, and so the unemployment rate. It's uncertain how it will affect the quality of education received, the decisions young people are making in terms of their routes towards employment, and how, if at all, it addresses local skills needs.

In 2012 the Local Government Association's analysis highlighted a distinct youth skills mismatch, finding that "more than 94,000 people completed hair and beauty courses despite there being just 18,000 new jobs in the sector".

In 2015 the UK Commission for Employment and Skills observed that:

"Employers value work experience, but the majority aren't engaged with schools and colleges to support young people to learn about and experience the world of work."

More than a quarter of businesses (28%) report having to provide at least some remedial training in English, numeracy and IT for school and college leavers, falling to 15% for graduate recruits, according to the CBI. It'll take time before we can see what effect the latest reforms have on this.

This briefing was written by Tamaris McCrone of the National Foundation for Educational Research in collaboration with Full Fact. This work has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation but the content is the responsibility of the authors and of Full Fact, and not of the Nuffield Foundation.

Correction 05/05/2015

The article originally said that one in seven young people are unemployed instead of one in six.