Have the government's tuition fee reforms worked?

- The number of home applicants to UK universities fell after the increase in fees, but broadly the application rate of 18 year-olds has continued to increase

- The application rate for disadvantaged young people was at a record high in January 2015

- The lowest earning 30% of graduates are expected to pay back less of their loan under the 2012 reforms, but the other 70% are expected to make higher repayments

- 73% of graduates are expected to have some debt written off compared with 32% under the old system

- Universities received an increase in funding per student, but inflation has eroded some of the gains

- It's probably too early to tell how much, if anything, the government is saving

- Recently-announced plans will see maintenance grants being replaced by loans, which will see lower-income students getting into more debt (although it's estimated two thirds won't pay any more as their debts will be written off). There are also proposals for a freezing of the repayment threshold for loans, meaning more of the debt would be paid back overall.

"The Coalition government has developed a package that is fairer than the present system of student finance and affordable for the nation."—Vince Cable, November 2010

"The big risk is that participation and social mobility will be damaged"—Professor Les Ebdon, November 2010

In 2012 the Coalition raised the cap on tuition fees for undergraduate courses to £6,000 for all universities, and to £9,000 in "exceptional circumstances" —which now 120 universities and conservatoires in England (the vast majority) are charging.

English-domiciled students entering university that year start making repayments once they earn £21,000 (a threshold intended to be linked to income growth) rather than £15,000 as before. They are charged an above inflation interest rate if they earn at least £21,000 a year, and their debts are written off 30 years after becoming eligible to be repaid, rather than 25 years after.

The government is to consult on whether to freeze the threshold at £21,000 a year for five years. Due to inflation this would put its real level at close to the original £15,000 level by the end of the freeze period, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

Different countries, different rules

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

This article mainly focuses on the impact of the reforms for English-domiciled students on undergraduate courses, who pay fees wherever they study in the UK.

The situation is slightly different for students resident in other parts of the UK—particularly so for those staying in Scotland to study who don't have to pay fees. Welsh students receive a fee grant of about £5,300 and receive a loan to bridge the difference. Northern Irish students studying at home also face a lower maximum fee level.

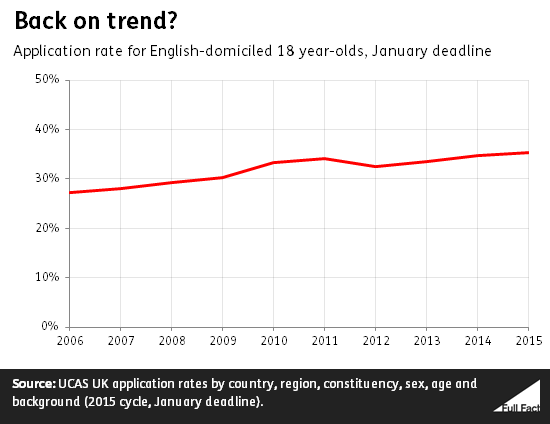

More 18 year-olds are applying

The application rate for English-resident 18 year-olds was at a record high in January 2015. The application rate did fall after the introduction of higher fees, but the long-term upward trend has continued.

The number of English 18 year-olds applying to university has risen since 2010, despite a downward trend in the number of 18 year-olds in the population.

The rise in application rates for young people in 2010 may have been influenced by the recession, with 18 year-olds choosing to remain in full-time education rather than enter a poor job market.

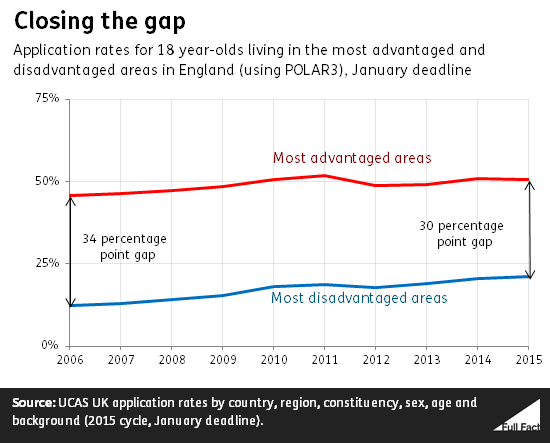

The application rate for disadvantaged young people is also rising

18 year-olds from disadvantaged areas reached their highest ever application rate at the end of the UCAS admissions cycle in 2014, and these gains have continued into the 2015 cycle—the January deadline application rate for this group was also at a record high.

18 year-olds from the least advantaged areas have lower application rates but the gap in application rates between the most and least advantaged areas has continued to shrink. The gap at the 2015 January deadline was at its lowest recorded level.

Application rates for young people from the most advantaged areas seem to have been the most affected—the fall in application rates in 2012 is concentrated among those in the advantaged areas rather than disadvantaged areas.

But the total number of applications fell

The total number of English-resident students applying to UK universities fell after the introduction of reforms, and is yet to return to the peak reached in the 2011 entry cycle.

This is reflected in the numbers enrolling too—English full-time undergraduate entrants fell from 356,000 in 2010/11 to 346,000 in 2013/14.

However, the reforms may have led to more people applying in 2011 than would otherwise have been the case. Students who wanted to avoid higher fees are likely to have decided against taking gap years.

To look beyond this effect, we can compare applicant numbers from the 2010 application cycle—the last one before fee changes were announced—to the latest figures. English-domiciled applicant numbers are down 2% on that year.

Decline in older applicants behind the fall

Of those groups experiencing a fall in the number of applicants from January 2010 to January 2015, applicants aged 20 and over accounted for the vast majority of the decrease.

But there's also been a further decrease in mature students not visible in these figures. The majority of mature students are on part-time courses—the application process for which is separate from UCAS. Instead we can look at the number of English-resident entrants to part-time undergraduate courses in the UK, which fell 48% from 226,000 in 2010/11 to 118,000 in 2013/14.

Representative body Universities UK (UUK) has said the introduction of loans in place of grants for part-time courses for the first time, the impact of the economic downturn and reductions in public sector employment are thought by universities to be behind the decline in part-time, mature students.

UUK's analysis found while there was some decrease in part-timers in Scotland and Wales too, the fall was significantly greater in England than the rest of the UK, suggesting tuition fees were a large factor in the decline.

The Independent Commission on Fees has expressed concern about the decline in terms of its effect on "second chance" students—which it says mature undergraduates tend to be—who return to higher education to improve their career prospects.

Supporting disadvantaged groups

The 2012 reforms didn't just change fees and loans. If a university wanted to charge the maximum £9,000 per year it had to commit to increasing the participation of under-represented groups. This could include outreach activities such as matching school pupils to a student mentor, or extending systems of bursaries and scholarships to disadvantaged students.

It's not clear if the extra financial support has increased participation: disadvantaged young people have shown no tendency to favour universities offering higher financial support, according to the Office for Fair Access.

Poorer graduates are better off, while others pay more

Over the longer run, the lowest earning 30% of graduates studying full-time will repay less under the new system than they would have under the old, according to estimates by the IFS. The remaining 70% are expected to have to pay back more under the new system.

Roughly 73% of graduates will not repay their debt in full, compared with 32% under the old system. The outstanding balance on the loan is written off 30 years after becoming eligible to make repayments.

The increases in fees are likely to hit male graduates harder. Female graduates tend to be employed for a shorter period and earn less on average. Male graduates are expected to pay back approximately 87% of what they borrow, while the average female graduate is expected to only pay back half, according to estimates from the IFS in 2012.

The government intends to replace the maintenance grant, which currently goes to students from households with pre-tax incomes of up to £25,000, with a system of loans starting in 2016/17. The IFS predicts around two-thirds of those affected by the changes will not pay any more than under the current system, because the extra debt will be written off. The remaining third will end up paying an average of £9,000 more than they would have (in 2016 money).

Universities are better funded

From 1989 to 2005, university attendance increased substantially. But government funding didn't keep pace with student numbers, leading to a 40% fall in funding per student, according to the Russell Group. The Coalition government reformed student finance to further shift the burden of payment away from public funding and onto graduates, in an attempt to increase universities' funding as recommended by the Browne Report (a review set up by the previous Labour government).

The reforms to student finance cut teaching grants to universities, but increased tuition fee income. This may eventually lead to an increase in funding per graduate of £4,300, according to IFS estimates in 2012. This would leave universities better financed than before. But, as the Browne Report set out, universities (and the departments within them) would also have to "raise their game" to meet student demand and so compete for the funding.

While the reforms may have led to an initial rise in income, the fee cap hasn't increased with inflation—leading some in the university sector to express concern over its decreasing real-terms value.

But we're not sure whether the taxpayer is saving

The most common way to look at whether tuition fees have lessened the burden on public funding is to look at the cost to the government of lending to an incoming year of students. This is expressed as the proportion of the money loaned that isn't repaid, and is known as the 'Resource and Accounting Budget' (RAB) charge.

A well-publicised estimate by London Economics indicated that an RAB charge higher than 48.6% would result in the new system costing more than the previous arrangement.

The IFS estimate that about 43p in each £1 of loans won't be repaid, and say that a saving of only around 5% per student has been made. The government estimate about 45p won't be repaid. However, as the authors of the IFS report point out, many of the factors that would change the estimates of the current RAB charge (for example, changes in the growth of the economy or increases in avoidance of repayment) would also change the RAB charge under the previous system. As such, the idea of a single RAB charge at which the new system 'costs more' than the previous system is unhelpful.

There's also reason not to interpret the RAB charge—which exists for accounting purposes—as the true cost of student loans. The government has to borrow money to pay for the loans, and the cost of doing so has to be taken into account in the RAB charge. The Treasury allows for quite a conservative assumption about how much the cost of this will be—as high as 2.2% above inflation. But some economists, such as Neil Shephard at Oxford University, have argued that the true cost will be more like 1.1% above inflation. This could make a significant difference—based on the IFS' estimates this would lead to an RAB charge of 31p per £1.

This doesn't mean the government's estimate is wrong, it just means that because the repayments are so difficult to predict it may be preparing for a greater loss than might be the case.

At present it's still too soon to tell whether or not real savings have been made.

And the system could be set to change again, with the government announcing it would consult on freezing the threshold for repayment at £21,000 a year. That would mean former students would start repaying their student loan at a lower income in real terms (once inflation is taken into account) and so the average student would repay a greater share.