As pupil absence rates increase, they do worse in tests at ages 10/11 and 15/16.

That was a key finding of new research from the Department for Education, based on 2013/14 data. It said that “every extra day missed was associated with a lower attainment outcome”.

But that doesn’t mean more absence causes worse performance. This research can’t prove that. We don’t know whether other factors, not measured by the research, are affecting pupils’ performance.

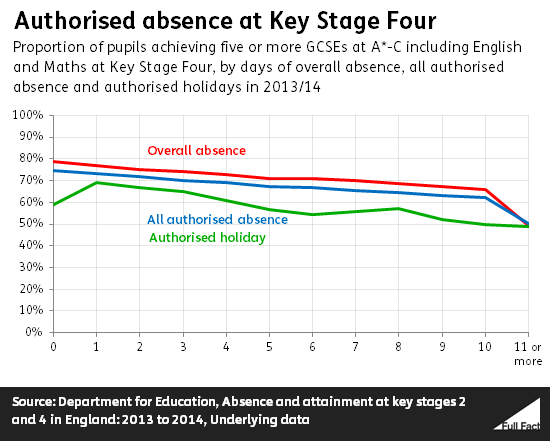

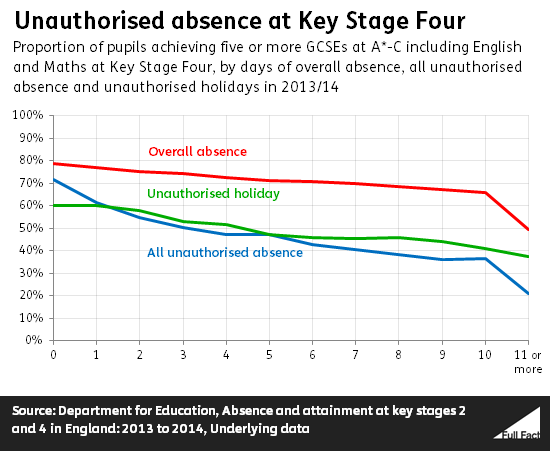

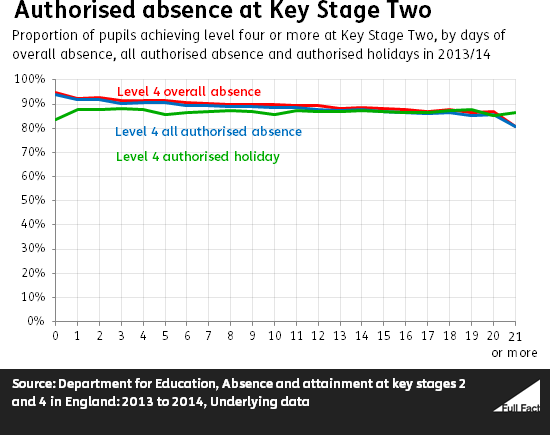

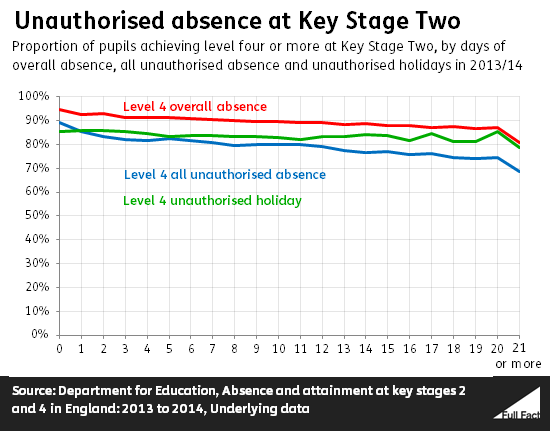

Even though there’s a link between overall absence and worse performance, there are exceptions, particularly if you just take a single missed day. When you drill down to look at the type of absence, authorised holidays at Key Stage 2 haven’t shown the same link.

A link is not the same thing as a cause

The research is careful in only talking about an “association” between extra days of absence and lower attainment. But the minister’s claim arguably implies there is a proven causal link.

The Department says it “has not claimed a causal link, and we have previously explained that in the statement the spokesperson said that absence ‘can’ (rather than ‘will’) affect GCSE performance”.

However you interpret what the minister has said, this research can’t prove absence causes lower attainment.

Pupils’ characteristics need to be factored in

When we previously factchecked claims made about the link between absence and attainment, it wasn’t clear if lower grades were down to days missed from school or the characteristics of pupils who tended to be absent.

Absences are higher among pupils eligible to claim for free school meals, for example. This is the measure generally used to indicate if a pupil is from a low-income family. The overall absence rate of pupils eligible for free school meals was 7%, compared to 4% of their peers.

Absence rates also vary by ethnicity. Children who are Travellers of Irish Heritage or Gypsy/Roma had the highest absence rates and Chinese and Black African children had the lowest absence rates.

Unlike earlier research, the 2013/14 analysis does take some of this into account.

It looks at whether the pupil is male or female, whether they are classified as having Special Educational Needs, what ethnic group they are in, whether they’re eligible for free school meals, and how well they were doing at school before the absence.

It finds that taking these characteristics into account, there is still a link between missing days from school and the likelihood that children do less well.

There may be important characteristics we don’t know about

Even then—and you’ll be getting used to this phrase by now—it’s still not possible to say that this proves that absence causes lower performance.

As Professor Stephen Gorard from Durham University has said, “absent pupils may be different to their peers in many ways not covered by the data available”.

When holidays are the reason for absence, the evidence isn’t consistent

Looking at holidays, most pupils still do worse the more days they take off. But not all age groups follow this trend.

At Key Stage Four—15 and 16 year olds—the greater the number of days of absence, the lower the pupils’ performance. That was true regardless of whether the absence was authorised or unauthorised.

At Key Stage Two—10 and 11 year olds—the trend was the same for unauthorised holidays. But for authorised holidays, there is a small link in the opposite direction. That is, pupils who had taken more days off tended to do better than their peers.

Either way, holidays alone don’t show large links between absence and performance.

In 2013/14 the proportion of unauthorised holidays taken by students at Key Stage Two and Four was greater than authorised holidays.