Overcrowded classrooms: bad and getting worse?

"The number of four-to-seven-year-olds being taught in classes of more than 30 pupils almost trebled in five years, according to official data." BBC News, 24 June 2013

Are our schools facing a crisis? Recently we learnt about the shortfall in school places across the country, which according to the National Audit Office, will mean that an extra 240,000 primary places will be needed by next year.

We also learnt that, according to some, new schools - in particular free schools - are allegedly not being built in areas of need. This morning, the BBC had more bad news for parents, claiming that the number of infant school classes holding more than 30 children had trebled in the past five years.

This piece of information is confirmed by the Department for Education's (DfE) latest statistical release on schools and pupils.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

According to a DfE statistical release in 2008 24,700 pupils were in classrooms with over 30 other classmates, and that number had almost trebled to 72,000.

So, what is causing this rise?

Pupil numbers

Although the rise in the number of pupils aged four to seven in large classrooms has been an ongoing phenomenon in recent years, the upward trend has gathered momentum in recent years, and between 2012 and 2013 the numbers went up by 52%, from 47,290 to nearly 72,000.

Large class numbers

What about the number of crowded classrooms?

To answer this question, it's best to make a distinction between classes that are "lawfully large", and classes that are "unlawfully large".

The BBC correctly reported that under the previous government, classes of more than 30 for this age group were proscribed altogether, unless schools could prove that there were exceptional circumstances. If schools could not explain class sizes above 30, they were considered "unlawfully large".

The 2012 School Admissions Code relaxed the circumstances in which pupils may be admitted where class sizes have already reached the 30-pupil limit. The DfE says that because the list of exceptions differs from those used in previous years, "results are not directly comparable".

The most recent list of mitigating circumstances includes:

- Children who move into the area outside the normal admissions round for whom there is no other available school within reasonable distance;

- Children admitted outside the normal admissions round with statements of special educational needs specifying a school;

(The full list is available here.)

In 2013, out of a total 54,298 classrooms across the country, 2,299 had 31 or more pupils. Of these 225 were unlawfully large, whereas the remaining 2,074 were lawfully large. This includes all state primary schools including free schools.

In 2008, out of 53,140 classrooms, 580 (around 1.1%) had 31 or more pupils. 200 of these were unlawfully large. So while there are more classes above the 30-pupil threshold, a smaller proportion of classrooms are currently unlawfully large compared to 2008, and the overall number of unlawfully large classes has remained fairly constant over the five year period.

(Source: Table 6b of the latest DfE statistical release)

Why has this happened?

As a 2012 DfE report on class size and education in England shows, this rise has long been expected.

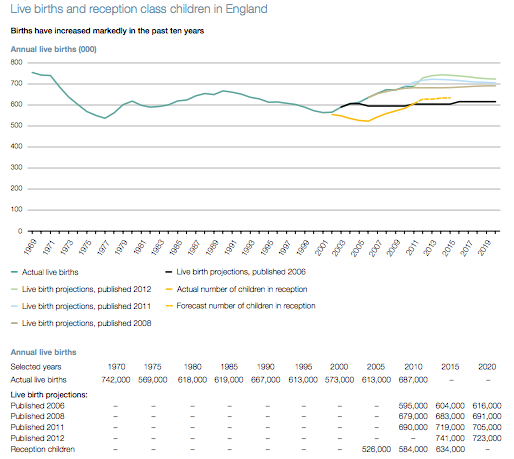

Annual births in England have increased every year since 2002. The National Audit Office also focused on the substantial increase in birth rates between 2001 and 2011as one of the main factors behind the shortfall in school places.

According to the DfE report, pupil numbers and average class size follow similar trends over time.

Crucially, the DfE adds:

"The recent and projected population increases are likely to increase demand for teachers and the number of class rooms, making it more challenging for Local Authorities (LAs) to keep Key Stage 1 classes within the legal limit of 30 pupils per class."

Of course, there is also a considerable regional variation within the average class size, as well as population projections. London is expected to experience greater population increases than other regions, and therefore a greater increased demand for teachers and class rooms.

How do we compare to other countries?

The graph below shows data from the OECD's 2012 Education at a Glance report, which illustrates the UK's placing among advanced economies for primary school class sizes. We need to be careful in how we interpret this data, given that it covers a wider remit than the figures we've seen so far.

While the DfE class size data relates to Key Stage 1 (4-7 years old) in England, the OECD figures cover all primary schools (up to age 11) across the whole of the United Kingdom. The data was also gathered three years ago.

Still, interestingly, in 2010 the average size of a UK classroom in state primary schools was 25.8, higher than the OECD average of 21.3.

The English average for 2012 is 27.3 primary school pupils per classroom.

So it's true to say that both the number of pupils attending large classes, and the number of large classrooms have gone up exponentially. Though this increase was largely expected, given the rising birth rates, long term demographic pressures are not the only factor at play. Amongst others, changes in the mitigating circumstances which allow certain schools to take on more pupils may also have contributed to the phenomenon.

----

Flickr image courtesy of masha krasnova-shabaeva