BBC Question Time: Recap and Factcheck

This week Question Time was set in the Staffordshire town of Cannock.

The topics covered this week included Brexit, and what the deal this week meant, gambling and homelessness and rough sleeping.

On the panel this week were Labour’s shadow treasury minister Clive Lewis, secretary of state for Northern Ireland Karen Bradley, Richard Walker, managing director of Iceland (the supermarket not the country), former President of John Lewis, Trevor Phillips, and journalist Julia Hartley-Brewer.

Obscure fact about Cannock not even tangentially related to politics: Cannock Chase, the area in which Cannock sits, is the smallest Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in the UK.

Join 72,547 people who trust us to check the facts

Subscribe to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Question 1&2: Brexit

The first segment of the show began with the audience asking whether “in trying to please all of the people, has Theresa May only succeeded in pleasing none?” It then moved on to asking whether or not “Mrs May’s Brexit meant Remain?”

Both questions involved a very long discussion amongst the panellists about what they thought of the deal and what exactly the withdrawal deal and any future trade agreement would allow the UK to do, and what it wouldn’t.

We’ve looked into this a lot recently, so here’s our summary.

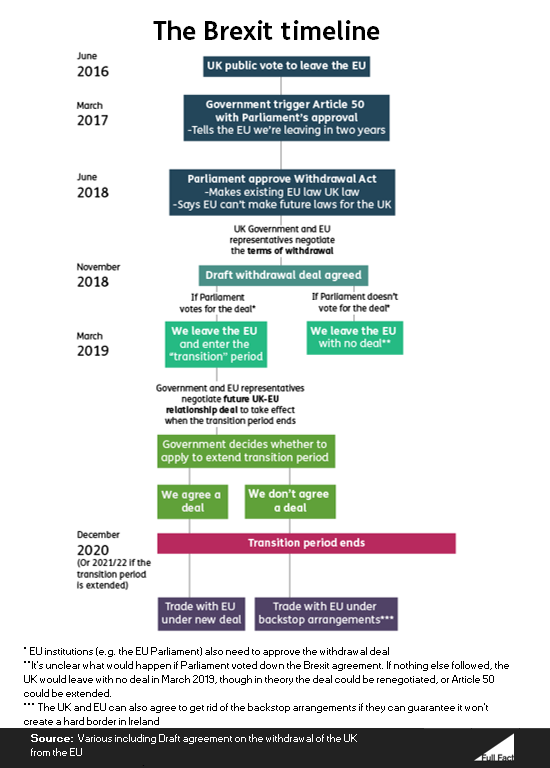

A Brexit “withdrawal agreement” has been recently agreed between the UK government and EU representatives. It now needs to be ratified by the UK parliament and other EU bodies.

The withdrawal agreement is not meant to amount to the final word on what the UK and EU’s future relationship will be. It is a transitional arrangement which sets out the exact terms of the UK and EU’s relationship immediately after exit day on 29 March 2019, and is meant to to give UK and EU negotiators more time to agree a wider deal on their future relationship, which would kick in later on.

The withdrawal agreement says that if we fail to agree a future trade relationship with the EU we will trade with them under the so-called “backstop” arrangements which includes a “single customs territory”—this has been described as being similar to a customs union.

The UK can’t decide to end the backstop arrangement of its own accord—this decision can only be made by a joint panel of UK and EU representatives. Some people, including Julia Hartley-Brewer on the show, have said this means the withdrawal agreement prevents the UK from leaving a customs union with the EU of its own accord.

We’ve created a timeline looking at the plan for Brexit:

Question 3: Gambling and Bet365

Moving away from Brexit the next point up for discussion was gambling. The question from the audience was “is Denise Coates, of Bet365, an astute businesswoman whose success we should celebrate or a business taking advantage of vulnerable people?” This was in reference to reports this month that Ms Coates, the online gambling company’s co-founder is the “UK’s best-pad boss”—receiving £265 million in 2017/18 including dividends.

Beginning the discussion David Dimbleby mentioned that “nearly half a million children under the age of 16 now gamble regularly ... children are encouraged to gamble by exactly this kind of Bet365 presence”.

A recent study from the Gambling Commission estimated around 450,000 11-16 year olds in Great Britain gambled in the past week. That was based on 14% of pupils surveyed in academies and maintained schools reporting having done so.

The Commission says it used data on the state school population in Great Britain to arrive at the 450,000 figure.

That means the figure for all 11-16 year olds across Britain who gamble weekly will be higher than the one claimed, because not all children go to the types of state schools involved in the survey. For example the estimated number of children at independent schools who gamble weekly isn’t included in the 450,000 figure.

We have other concerns the calculations may underestimate the true figure in other ways, and we’ll update this piece when we find out more.

The most common form this takes is “informal” gambling like private bets or playing cards with friends, and national lottery scratchcards, rather than occurring in ‘formal’ settings like casinos or bingo halls.

The same report also found two-thirds of the children surveyed have seen gambling adverts on TV, 59% on social media and 53% on other websites. And 12% actually followed gambling companies on social media.

While these figures refer to all gambling, there’s also a measure of “problem gambling”, where people demonstrate several traits associated with having gambling problems, such as feeling withdrawal when trying to cut down or resorting to stealing money.

1.7% of children screened as problem gamblers in the study, and another 2.2% were “at risk” of problem gambling (meaning they screened for a number of traits, but not enough to qualify as problem gamblers). Both figures had risen compared to the previous year. These figures are only as good as people’s willingness to admit to certain activities.

Mr Lewis then mentioned that “nurses are going to food banks”.

There’s been anecdotal evidence and media reports of nurses using food banks and we wrote about this last year. The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) has reported 2% of its members using a food bank in the previous year, though we don’t know to what extent members of the RCN are representative of nurses generally. We’ve asked them for more information.

Additionally this summer the Cavell Nurses' Trust ran a survey of around 1,100 UK nurses finding that 9% had ever used a food bank. We don’t know how representative the nurses in the survey are of nurses generally as the group wasn’t selected to be necessarily be representative of the entire nursing workforce and the results weren’t adjusted for this either.

Question 4: Rough sleeping

There were only three questions on the show this week, and the final one was: “One in 200 Britons are sleeping rough or in temporary accommodation. How has this been allowed to happen?”

Once again David Dimbleby got in with the first claim by adding a bit more context for viewers: “These are the latest figures that have come out, one in 200 sleeping rough or in temporary accommodation.”

The figures our Question Time host was referring to come from a new report by the housing charity Shelter. It found that 320,0000 people were recorded as homeless in Great Britain—so not including Northern Ireland—in the period roughly covering 2017/18. That equates to 1 in 200 people.

The figures are based on official data for England, Scotland, and Wales, as well as research on hostel bed spaces from the charity Homeless Link, and Freedom of Information (FOI) requests which Shelter submitted to councils. We’ve broadly been able to replicate Shelter’s calculations and, while they involve a degree of assumption, they seem reasonable to us.

The 320,000 figure covers adults and children who are living in temporary accommodation, single people not entitled to temporary accommodation who are living in hostels, rough sleepers, and people living in temporary accommodation arranged by children’s services. The figures may be an underestimate as for some of these groups information isn't available in Scotland and Wales.

Some of the calculations involve a degree of approximation (for instance, we only know the number of households, not total people, in temporary accommodation in Scotland and Wales)—but Shelter’s approach seems sensible to us. For example, where data on the number of people in temporary accommodation wasn’t available for Scotland and Wales, Shelter assumed there to be the same number of people per household in temporary accommodation as in England. We’ll look into the figures further and write more on this soon.

Julia Hartley-Brewer was then asked for her view on the figures and made the point that “the vast, vast majority of those people do have a roof over their head”.

Around 315,000 of the 320,000 people were recorded as living in temporary accommodation or a homeless hostel. In most cases, councils have a duty to find temporary accomodation for people who are homeless.

“Rough sleepers” are people who are sleeping on the streets. Estimates for this aren’t perfect but there were an estimated 4,800 people sleeping rough in England and 345 people in Wales in autumn 2017. We’ve explained the definitions of homelessness in more detail here.

Both Richard Walker and Clive Lewis made the claim at various points that 1.5 million people in the UK are destitute.

The claim is sourced to a report released recently by the Professor Philip Alston, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights.

That’s not the original source of the figure though—Professor Alston got the number from a recent study by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. We’ve not yet been able to check how accurate the figures in the JRF study are, although they acknowledge themselves that the figure has a wide margin of error. (It’s worth noting that the claim is slightly different in the study—that 1.5 million people “were destitute in the UK at some point during 2017”. In other words, not all of the 1.5 million people will have been destitute at the same time; people can move in and out of periods of destitution.)

Destitution is defined in the study as people who, in the past month, either went without two or more of six essentials: shelter, food, heating or lighting their home, clothing and footwear appropriate for weather, and basic toiletries; or were unable to purchase these essentials for themselves, even if they didn’t go without them.

The JRF study also reported that, according to their estimates, the number of people experiencing destitution had probably declined by around 25% compared to their previous study in 2015, although again there is a large margin of error attached to the figures.

We’ll continue looking into this.

Clive Lewis then said “We have 5,380 social homes that were completed last year and a waiting list for council houses of 1.2 million and that is on the watch of this Conservative government.”

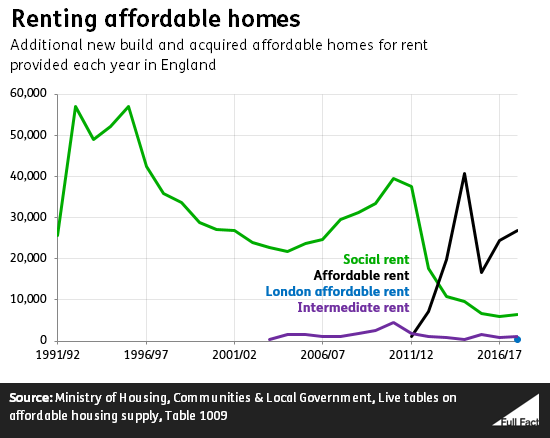

5,385 homes for social rent (50% of market value) were completed in England in 2017/18. Including other homes that were bought or converted for social rent there were 6,463 homes added to the supply of social rent properties.

In all there were around 47,000 affordable homes added to the supply in 2017/18, that includes homes for things like affordable rent (up to 80% of market value) and shared ownership.

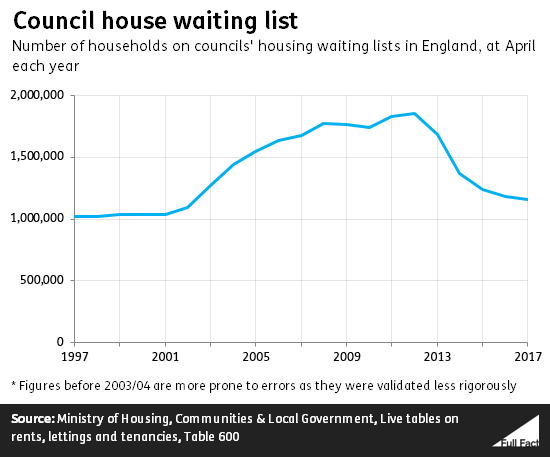

There were 1.16 million households on waiting lists for council housing across England in April 2017. That’s a reduction of 38% since the peak in 2012 and at a similar level to 2002.

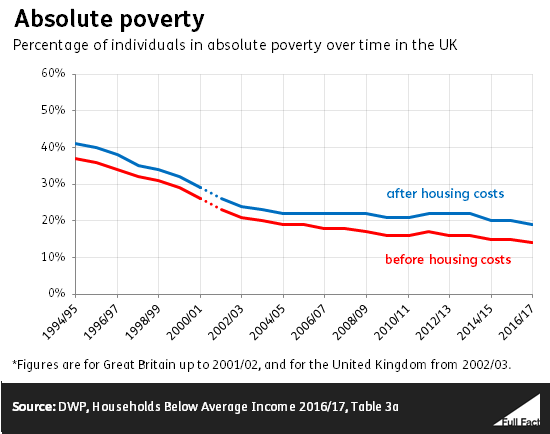

Returning to the topic of poverty, Karen Bradley said: “there are one million fewer people living in absolute poverty today compared to 2010.”

It's correct that there were one million fewer people in absolute poverty (before housing costs) in 2016/17 than in 2009/10. As a percentage it’s decreased from 16% to 14%. But there are other measures of poverty. We've written more about them here.

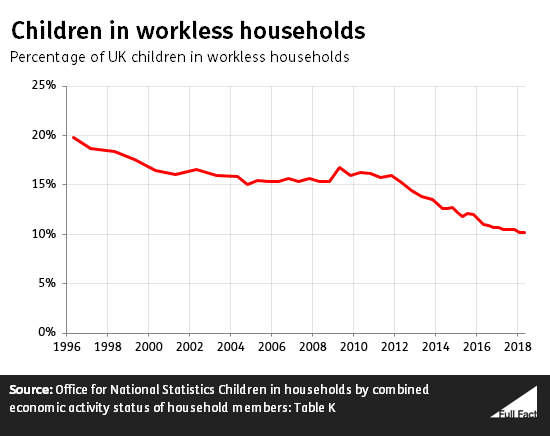

We assume Ms Bradley meant to say 630,000. In April to June 2018 there were 637,000 fewer children under 16 in workless households in the UK than in April to June 2010. That’s a 33% decrease.

Taking into account population change the proportion of children in workless households has fallen from 16% to 10% of all children over that period.