The pub chain JD Wetherspoon has recently distributed beer mats in its pubs making a number of claims about the EU and outlining what Wetherspoon chairman Tim Martin thinks the UK government’s Brexit policy should be. These beer mats have also been the subject of a number of news articles.

We were asked by Full Fact readers to see if these claims stack up.

“Free Trade (ie “No Deal”) means lower prices” … “Ending tariffs means lower prices in shops and pubs!”

The initial claim - that 'Free Trade' and 'No Deal' mean the same thing - is misleading. Exiting the EU without a deal wouldn't necessarily mean that the UK would adopt a particular trade policy afterwards; it would mean that the government would have the option to adopt it, within the constraints of World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules.

There have been calls for the UK in a no-deal scenario to follow the lead of countries like Singapore to operate with few, if any, import tariffs. However, this is not currently government policy, and it's also possible that the government could choose to raise import duties following a no-deal Brexit.

The UK government is currently negotiating the terms of its exit from the EU, and the shape of the UK and the EU’s future relationship. The UK's aims include what it calls a “deep and comprehensive economic partnership”, with the EU, including establishing a “free trade area for goods”.

At the moment, the UK is part of the EU Customs Union. This means we can’t face or impose tariffs (which are like taxes) on our trade with other countries in the customs union.

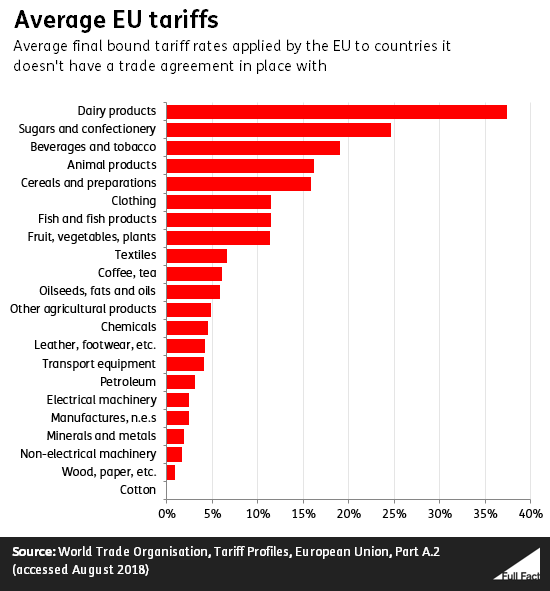

The EU does set some tariffs on trade that comes in from the rest of the world, outside the customs union, which means some UK imports face tariffs too. That’s unless the EU has a specific trade agreement with the countries involved. It also waives tariffs on most goods from almost 50 developing countries under its Everything But Arms policy.

If the UK were to leave the EU without a deal in place we would trade with the EU under the rules laid down by the World Trade Organisation: an international body which regulates world trade. This is what people mean by trading “under WTO terms” or a “no deal Brexit”.

This means the UK could remove tariffs on some goods that currently face them via the EU.

Ending tariffs wouldn’t necessarily lead to “lower prices in shops and pubs”

It’s generally accepted that reducing tariffs in and of itself lowers consumer prices: after all, these are an additional tax on products.

There’s inherent uncertainty to any predictions, but the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has estimated that abolishing tariffs entirely could reduce prices faced by households by about 0.7–1.2%.

But tariffs are just one factor that impacts on the prices that consumers actually pay.

Removing tariffs like this is only possible if the UK leaves the EU’s customs union. Doing this would likely lead to the need for new checks on goods moving between the UK and the EU, which would introduce new costs on this trade.

The IFS concludes that these new costs would probably be greater than the limited savings from abolishing tariffs: leading to higher costs for consumers.

The UK government has recently published a series of guidance notes explaining how people should prepare for a no-deal Brexit, giving some clarity as to what these “non-tariff barriers” would look like. The trade guidance it has published suggests that businesses might consider buying new software or hiring “a customs broker, freight forwarder or logistics provider” to help them navigate these new requirements.

“The vast majority of the public strongly objects to the crazy government plan to pay £39 billion to Brussels, with nothing in return” … “That’s £600 for every man, woman and child in the UK—or £60 million per MP.”

In a poll conducted by ICM on behalf of the Guardian in August 2017, respondents were asked whether they thought that “paying an ‘exit fee’ of up to £40bn … as the UK’s contribution to spending commitments made by the UK when the UK was a member” was acceptable or unacceptable. 75% said they thought it was unacceptable.

Polling organisation YouGov has noted that people’s responses to this question seem to depend a lot on how the question is framed. Respondents tend to be more supportive of the lower figure in a range of options and less supportive of higher figures. In this case the £40 billion was the highest figure provided.

The size of the UK’s “divorce bill” with the EU is estimated to be £35-39 billion. We’ve written more about that here. Dividing £39 billion by the population of the UK and the number of MPs does give you about “£600 for every man, woman and child in the UK — or £60 million per MP”.

“Lawyers have repeatedly said that there is no legal obligation to pay [a Brexit divorce bill].”

A House of Lords report has argued that legally the UK isn’t required to pay a penny. This has been disputed by some legal experts, and the report itself acknowledges that there are “competing interpretations”. The Institute for Government has suggested that, if the UK refused to pay the exit fee, the EU might seek redress through the International Court of Justice or the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

“People pay these protectionist tariffs every time they shop – and the government collects the money and sends it to Brussels.”

The UK Government collects tariff revenues on goods it imports from states that don’t have tariff-free trade with the EU, and contributes this to the EU budget, after keeping 20% of this money to cover “collection costs”. The UK then receives a proportion of its contribution to the EU budget back in EU-funded projects in the UK (just less than half in 2017), though less than many other member countries.

“… all EU products can be replaced by similar alternatives from the UK—or from the 93% of the world not in the EU.”

This 93% figure seems to refer to the proportion of the world’s population that is in not in the EU, and is correct. Another way of considering this issue is the proportion of the world’s economic activity (measured in GDP) that is accounted for outside of the EU: an estimated 78% in 2016.

Whether consumers would want to swap EU goods like champagne for English sparkling wine is a matter for them.

“Our good friends in countries like Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Switzerland and Canada have slashed tariffs – their citizens are better off as a result, and their economies have thrived.”

This isn’t a straightforward claim, and there’s no definitive way of measuring the impact that tariff changes might have had on those countries’ economies.

Nor is there an easy way of summarising how low a country’s tariffs are, because they can vary a lot.

One way to compare what sort of tariffs different countries charge on their imports is to compare their average World Trade Organisation (WTO) tariffs.

This isn’t a perfect measure of how “free” a country’s trade is, as it doesn’t take account of any preferential trade agreements that individual countries or groups of countries have negotiated. In the case of the EU, for example, most trade takes place with countries that have negotiated improvements on these WTO rates.

It also doesn’t tell you anything about trade in services. This isn’t subject to tariffs, but can face other non-tariff barriers to cross-border trade.

Countries have two sets of tariffs: “bound tariffs” and “Most Favoured Nation” (MFN) tariffs. The bound tariff is the “upper bound”: the amount that countries have pledged to the WTO that they won’t exceed.

The MFN tariffs are the ones that are generally used, and must be applied to all WTO members a trade agreement isn’t in place with. In WTO parlance this means that all countries are treated the same as the “Most Favoured Nation”. There can be a large discrepancy between these two figures.

Hong Kong is the only place in the world to remove all of its tariffs, and in general, agricultural goods are subject to higher tariffs than other goods.

Switzerland’s average MFN tariff, for example, is increased by the high tariffs it applies to agricultural products: on average 35%.

Singapore’s average MFN tariff is zero, but this hides two details. One is that it retains a small average tariff on beverages and tobacco: 1.6%. The other is that it has a much higher average “bound tariff” of 9.4%: the level that the country can raise its tariffs to without breaking WTO rules.

“And our good friends in countries like the USA and India are keen to do trade deals with us.”

Both the USA and India have expressed interest in agreeing trade deals with the UK. These will be complex to negotiate and will require the UK government to make trade-offs.

For example, in a trade deal with the US, how much would the UK want to coordinate the two countries' very different regulatory systems (the prospect of chlorine-washed chicken for sale in the UK is often raised as a concern by UK consumers)? And in a trade deal with India, would the UK want to ease immigration rules for Indian workers?

It is generally thought that new trade deals will take the UK several years, at the very least, to negotiate. The more these trade deals seek to do—for example, the more non-tariff barriers they seek to eliminate—the longer they will take.

--

Robin Wilkinson is a Senior Research Officer from the National Assembly for Wales Research Service, on secondment with Full Fact