The Brexit timeline

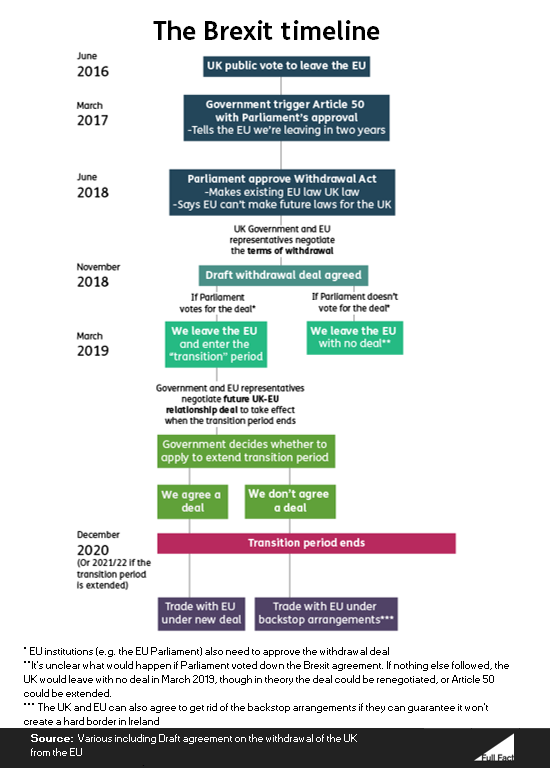

We’ve had no shortage of Brexit-related things to explain to explain in recent months—from the Irish backstop and transition periods, to WTO terms and no deal preparations—but it can be hard to understand how all of the pieces fit together.

So we’ve put together a timeline of the Brexit process. It briefly sums up the key issues and events you might want to know about, presenting them in chronological order (as far as that’s possible) to make it clearer how they all fit together. Throughout, there are links to related content we’ve published if you want to take a deeper dive into certain areas.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Already in place: Article 50 and the EU Withdrawal Act

After the UK voted to leave the EU in June 2016, the first key step on the road to Brexit was the triggering of Article 50—the EU’s legal provision for countries wishing to leave the EU. The government did this following parliamentary approval in March 2017, setting a two-year countdown to when we will officially leave the EU: on 29 March 2019.

It’s possible that Article 50 could be extended or revoked. We’ve written more about this here.

The next key step was for parliament to pass the EU Withdrawal Act, which happened in June 2018. It sets out that, after we exit, the European Union will no longer be the source of any UK laws. That means new EU laws won’t affect the UK, although the government will transfer many existing EU laws (which do affect us) over into UK law.

But the process of exiting is not quite as clean as it might seem. Although we are officially out of the EU from 29 March 2019, the full terms of the Withdrawal Act will probably not apply until further down the line, because UK and EU negotiators don’t think they’ll manage to sort out the whole of our future relationship by next March.

The heart of current negotiations: the Withdrawal Agreement and Transition Period

The UK and EU negotiators agreed on the text of a withdrawal agreement in November 2018.

This agreement sets out the exact terms of the UK and EU’s relationship immediately after exit day on 29 March—but it does not amount to the final word on what the UK and EU’s future relationship will be. Rather, it is a transitional arrangement, designed to make the separation process smoother. It covers things like trade, law, and immigration.

A key part of the withdrawal agreement is that there will be a transition period, running from exit day on 29 March until the end of 2020 (although the UK can apply to extend it by one or two years). During transition the UK would officially be out of the EU and not be represented on EU bodies, but would still have the same obligations as an EU member. That includes remaining in the EU’s customs union and single market, contributing to the EU’s budget, and following EU law.

The main reason for the transition period is that the UK and EU don’t think they have enough time to agree all the terms of their future relationship by 29 March 2019. The transition period is designed to give them more time to iron out all the details of their future relationship, including a possible free trade deal (we get on to what the future deal could look like further down).

- We explain the difference between the transition period and a free trade agreement in more detail here.

- We also have an explainer on the “divorce bill”, which is the amount of money we have to pay the EU as part of leaving.

If a withdrawal agreement is signed off it would come into effect on 29 March 2019. That would then lead to a transition period until the end of 2020, and from 2021 the UK and EU would enter a new relationship, possibly underpinned by a free trade deal.

Possible roadblocks: the Irish backstop

Before it’s made official, the withdrawal agreement has to be approved by the UK parliament. The UK government and EU negotiators have agreed a draft text, but many MPs object to it, and say they will not vote for it.

MPs were set to vote on it on 11 December 2018, but the government has postponed this as it expected to lose the vote in parliament. The Prime Minister is currently seeking to “secure further assurances” from the EU on the agreement before she brings it back to parliament.

One of the main points of contention is the Irish backstop.

In short, the backstop is a position of last resort that kicks in if the UK and EU fail to agree any kind of future relationship by the end of the transition period.

It’s designed to ensure that the Irish border remains open as it is today, even if all other negotiations fail. Some MPs don’t like it because it would result in what’s called a soft Brexit where the UK remains highly aligned with EU markets and rules.

Some also object because the UK can only opt out of the backstop if a joint panel of UK and EU representatives think it’s no longer necessary. The withdrawal agreement states that this will only occur if an alternative arrangement is found). This means the UK cannot leave it without EU consent.

The Democratic Unionist Party in Northern Ireland opposes the backstop because it would lead to some checks on goods entering Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK, with Northern Ireland more closely aligned to EU customs rules. They think this threatens the integrity of the union between the Northern Ireland and the rest of the UK.

Possible roadblocks: the meaningful vote and the possibility of no deal

Parliament’s decision on whether to approve the withdrawal has been called the meaningful vote. If parliament votes in favour of the withdrawal agreement, it’s set to come into force on 29 March 2019.

MPs will also have a chance to suggest amendments to the withdrawal agreement, and if the deal passes in an amended form, it’s possible that the government would have to go back to the EU to seek approval for an amended deal. It’s hard to know how this would pan out.

If parliament rejects the deal, the government has to make a statement on how it proposes to move forward. Parliament would then vote on that plan of action and could vote on amendments—essentially it could instruct government how to proceed with Brexit. We’ve written more about this here.

That could mean the government has to go back and negotiate further with the EU or accept that no deal can be reached.

A no deal Brexit means leaving without the proposed withdrawal agreement to smooth the exit process. It would likely lead to disruption, with overnight changes in how our borders and trade with the EU are regulated on exit day.

- This piece from the independent think tank Institute for Government explains that there are different ways that “no deal” could unfold, and some of the possible consequences of each scenario.

- We’ve looked into some of the things that could happen in the case of no deal here and here.

- We’ve also explained the meaning of WTO terms—on which the UK would trade with the EU in a no deal scenario.

Possible roadblocks: EU pushback

The EU have agreed the current draft of the withdrawal agreement. However Mrs May is trying to seek further reassurances from the EU on the matter of the backstop, following concerns raised by MPs.

Senior EU figures have repeatedly said that there is no option to renegotiate the agreement itself, but there is room to provide additional “clarifications and interpretations” on the backstop issue.

(If any renegotiation were to happen, it is more likely that it would be over the non-binding “political declaration” on the intended future trade relationship than the legally binding withdrawal agreement.)

Would could a future trade agreement look like?

If the withdrawal agreement is approved by parliament, the UK and EU would spend the transition period trying to agree on a future relationship. There would be a possibility to extend the transition period for a set period if both sides agree to do so.

The “political declaration setting out the framework for the future relationship” (a statement of intent accompanying the withdrawal agreement that isn’t legally binding on its own) states that the UK and EU would form “separate markets and distinct legal orders” in a future relationship.

But it also aims for a future “trading relationship on goods that is as close as possible” with the UK and EU having common rules in some areas, and no tariffs on any trade in goods. This would result in the UK having a fairly close alignment with the EU’s customs territory.

- The political declaration alludes to the possibility of “facilitative arrangements and technologies” to manage customs in a future UK-EU trade deal. Such an approach has previously been called “max fac” and we’ve explained what it means here.

This model of trade deal is closer to the one Norway has with the EU than the one Canada has (two oft-referenced deals in debates over what a UK-EU trade deal could look like). The “Norwegian” model is based on a higher degree of access to EU markets, and a higher degree of following EU rules (although the UK’s deal is unlikely to be as closely aligned as Norway’s). Some continue to advocate a “Canadian” model for a trade deal—based on lower market access and lower levels of EU regulation—although it’s unclear that such a shift could be made this late in the negotiations.

- We explain the Norway and Canada models in more detail here.

Update 13 December 2018

We've updated the piece following recent events.