Are British workers less productive than Germans and French?

It takes on average a British worker to Friday to do what equivalent workers in Germany and France will complete by the end of Thursday afternoon.

Chuka Umunna, shadow business secretary

British workers have a productivity problem, argued the shadow business secretary Chuka Umunna on the Today programme recently. Injecting an element of European competition into his arguments for why the UK needed to focus more on boosting the number of high-skilled jobs in the economy, he said British workers are less productive than those in France and Germany.

What he says is basically correct. His statement suggests that UK workers are at least 20% less productive than those in France and Germany — as ending work on Thursday means working four days out of five, so 20% fewer hours per week.

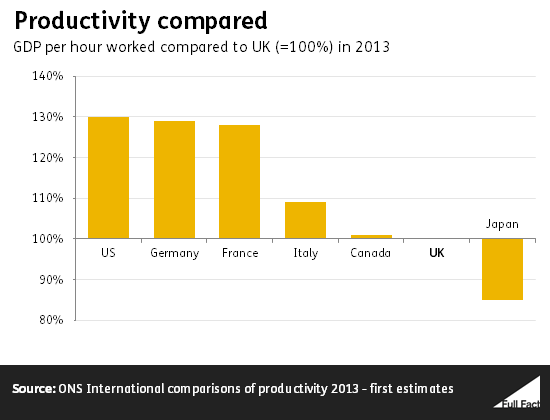

The latest relative productivity numbers looking at GDP per hour from the Office of National Statistics are below. The numbers are based at UK=100 so the fact that the German index is 129 means that Germany has 29% higher GDP per hour than the UK.

One could quibble with the numbers in various ways. First, these are calculations per hour and UK workers work more hours than Germans or French. According to the OECD, in 2013 the British worked an average of 1,669 hours a year, compared to 1,388 in Germany and 1,489 in France.

The position looks a bit better on a GDP per worker basis. Yet even on this measure the UK lags behind. If the UK's GDP per worker was 100 in 2013, France's was 14% higher at 114, Germany's 7% higher and the US 39% higher. More importantly, it is reasonable to think of controlling for differential hours when looking at international productivity. Efficiency is not raised simply by working more hours.

The productivity numbers also vary from year to year. The UK's position looked stronger before the crisis, and it is unclear how much of the gap is due to cyclical factors. British workers did bridge some of the international productivity gap in the decade leading up to the crisis, but they still lagged in terms of GDP per hour.

The numbers are also affected by the fact that the employment rate is relatively high in the UK. Unemployment is much higher in France than in the UK, for example — at 5.9% in the UK in October 2014, compared to 10.2% in France according to the OECD. So the least productive individuals are therefore not employed, which flatters the French productivity numbers. But it cannot explain the difference with Germany or the US.

Labour productivity partially reflects differences in capital invested per worker. Capital per worker levels are higher in Germany than the UK, for example.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Verdict

It's true to say that on the basis of GDP per hour, British workers are less productive than those in Germany and France, so much so that they would finish by Thursday what a Brit would do by Friday. But as UK employees work more hours over the year than those in France and Germany, and there is a high rate of employment, it's important to put these numbers in context.

Review

The article correctly confirms the statement by Labour's shadow business secretary that output per hour worked is higher in competitor nations. This is a long-standing problem which appeared to be diminishing in the years running up to the financial crisis but has resurfaced since then. The article points to the need to place these numbers in the context of better employment performance in the UK as well as longer working hours than our European competitors.

Yet, the relatively strong UK productivity performance before the crisis begs the question whether the factors underlying this will re-emerge once growth resumes. The literature points to higher UK investment in information technology and related intangible assets at that time, at least relative to France and Germany. These investments occurred primarily in service sectors which form a larger share of UK economic activity. It's also important to have workers with the required skills to complement this investment. Chuka Umunna's emphasis on having the right skills also seems broadly correct.

This article was written by John Van Reenen, director, Centre for Economic Performance at London School of Economics and Political Science and originally published on The Conversation.