Why the UK is being asked to pay £1.7 billion to the EU

The European Commission has asked the UK to contribute an extra £1.7 billion to its budget by 1 December. The Prime Minister's words to MPs this week were defiant:

"Britain will not be paying €2 billion [£1.7 billion] to anyone on 1 December, and we reject this scale of payment."

How has this come about? Why has it come as such a surprise? And can the UK do anything about it? We've put together a short guide to explain what's happened.

Most of the UK's payments to the EU are based on the size of the economy

All EU member states pay in to the EU budget and all get something back. The UK paid £8.6bn more to the EU budget than it got back in 2013, so it's one of the countries that contributes more than it receives - at least as far as the budget is concerned.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

By far the biggest chunk of what we contribute is a payment called 'Resource-based Gross National Income' (GNI): a sum based on how large a country's economy is (measured by the Office for National Statistics in the UK). As David Cameron mentioned in the Commons this week, this means that when the economy does well compared to other nations, we're asked to pay a bit more, and vice-versa when the economy does less well.

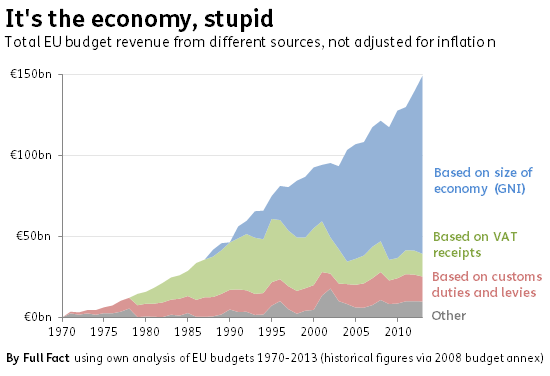

75% of the EU's money comes from GNI-based revenues, so a lot rides on how everyone measures the size of their economies. This hasn't always been the case. 20 years ago other payments based on members' VAT receipts and customs duties on their imports were more important.

As shown by the blue area below, GNIs came from nothing in the early 90s to become the most important contributor to the EU budget - although the figures aren't adjusted for inflation.

Adjustments to payments happen all the time, but this is an unusually large one

'Adjustments' to member states' payments happen every year, usually because budgets are initially based on estimates of the size of countries' economies and these get revised as more information comes to light and the estimates get more accurate.

This year is different. Member states were asked by the EU Commission to resolve problems with how they have measured the size of their economies dating back to 2002. But addressing this 'historic issue' in one fell swoop means this year's adjustments pack an especially powerful punch. It also implies that future years will return to lower adjustment levels now the issues have been resolved.

The economy has been bigger than we thought it was

EU law requires that member states measure the size of their economy according to EU standards. The UK hasn't been fully compliant with these standards, so statisticians at the ONS have spent the last year revising old estimates of the size of the UK economy. Some, though not all, of these changes have had a generally upward impact on the figures the EU uses to determine the UK's contribution to its budget.

The resulting increase in the estimated size of the UK economy relative to other nations - specifically between 2002 and 2009 - is what's caused the EU to ask for more money. If the Commission had known the size of the UK economy at the time, it would have charged us more, so the £1.7 billion represents the 'backpayments' following the counting changes.

Not every country has had the same experience of course. Some - like France and Germany - have been awarded discounts through having 'overpaid' in recent years.

Changes to how we measure the size of the not-for profit sector has had the biggest impact

A number of outlets have reported on how the economic productivity of sex workers and the trade in illicit drugs has been a driver of the upward revisions of the UK economy.

Actually, while this has had some impact, the biggest factor is changes to measuring the contribution of the not-for-profit sector: mainly charities and universities. Some of the methods used to calculate their economic activity up to now have been used since the 1990s, so they've been updated. The ONS provides detailed figures on how each change has affected the national figures.

Who knew what, when?

In spite of the Financial Times breaking the news (£) about the payments last Friday, the timeline of events started some time before that.

Work began to revise the UK's economic figures to comply with EU rules last summer. The large upward effects this had on the UK's GDP were being advertised back in May this year.

The Office for National Statistics submitted the UK's economic figures to the EU Commission a few days before the 22 September 2014 deadline to be checked by officials there.

The Commission claims to have informed member states of the financial impact of the new data on 17 October - a week before the reports came out, though it's not clear how much detail was given out.

So this wasn't necessarily a complete surprise - the foundations were being laid long before this week.

What happens now

The EU Commission told Full Fact that if member states are 'late' in repaying, it sends them a reminder and starts to levy penalty interest on the payment, due from the first day of delay. Each month of delay adds 2.5% interest on to the amount. It's not yet clear how much exactly the penalties would amount to. The Commission also pointed out that it had virtually never had any delay in member states paying monthly contributions.

However, it did note that member states could - as some had in the past - legally challenge the claims made against them.

It's also possible, of course, that the UK and the EU Commission could come to a mutual arrangement to avoid any of this.

IMAGE CREDIT: PATRICK GEPAT