Can we believe the lockdown sceptics?

Few people could have imagined last Christmas that in three months it would be illegal for them to leave the house.

Yet lockdowns have become so normal this year that it can be easy to forget what an extreme and unusual policy they are. They curtail people’s freedom and can harm almost every aspect of their lives. If the public are going to support a lockdown, they are entitled to ask for evidence, at least, that the alternatives are worse.

In the broadest sense, however, this is very difficult to know for sure. “Lockdown” has already meant many different things in different times and places, which makes it hard to generalise.

In total, considering all the effects on healthcare, the economy and people’s happiness, it is possible that the lockdowns we’ve experienced caused more harm than some of the alternatives—but it will take years to know the full effects of what we did, and we will never know the effects of things we did not try.

For now, a detailed government estimate suggests that locking down in the spring did save many thousands of lives, compared with doing nothing, largely because it prevented the health service being overwhelmed.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

The lockdown sceptics

Even so, some people are confident that lockdowns in general are a bad idea. They “cause more harm than good” in the opinion of Nigel Farage and Richard Tice. They would prefer a strategy of “focused protection” of high-risk individuals, as set out in the Great Barrington Declaration—although in the opinion of the government’s scientific advisors, and many experts in the field, this strategy would not work.

“[Lockdowns] don’t solve anything, they don’t break any circuits, they don’t break any fires,” the journalist and broadcaster Julia Hartley-Brewer said on Question Time on 10 December. “All they do is delay the problem.” Yet delaying the problem until a cure or a vaccine is ready for widespread use might be a good idea.

Others oppose lockdowns because they say they do not actually stop the virus anyway. On the face of it, this is a tough argument to make.

If you agree that Covid-19 spreads through contact with an infected person (which it does), then it is hard to see how banning human contact could fail to reduce the spread. However, many people sceptical of lockdowns have claimed that this is exactly what the data shows.

The Mail on Sunday columnist Peter Hitchens claims that it is “not possible” that the first lockdown in the UK caused the decline in daily deaths that followed, because he says the decline happened too early.

In a widely viewed YouTube video, the author and public speaker Ivor Cummins claims that the real reason that daily deaths declined in the spring was that the UK was reaching “herd immunity”—meaning that the virus was running out of people to infect.

He and the former Pfizer scientist Dr Mike Yeadon, in a Facebook video, an article on lockdownsceptics.org and several interviews on talkRADIO (now deleted from YouTube but still visible on Twitter), have both claimed that much of the population was already immune to Covid-19 before it arrived in the UK, perhaps through previous exposure to similar viruses. This, they also said, would stop the virus spreading significantly afterwards.

We must not dismiss the lockdown sceptics’ claims out of hand, just because they sound like something we wish was true, or because they lie outside the mainstream version of events. Mr Hitchens, Mr Cummins and Dr Yeadon all say that we should base our views on evidence, and on that we agree with them.

However, on the overwhelming balance of the evidence, their claims are wrong.

What does the evidence say?

On 16 March, the Prime Minister Boris Johnson made a televised statement saying "now is the time for everyone to stop non-essential contact" and on 23 March he told people they “must” stay at home, which is generally understood as the start of lockdown.

At the time, few Covid tests were taking place, which makes it difficult to track the infection rate directly.

However, we do have good data on the number of people who died each day with the disease mentioned on their death certificates. This allows us to roughly track the rise and fall of infections, because if more people are infected, we would expect more people to die.

If there was a sudden fall in the number of people catching Covid after 23 March, it should appear as a sudden fall in the death figures a while afterwards, because it takes some time for an infected person to die. The question is how long you should expect this time lag to be.

Research on this question produces different estimates, but two highly cited papers give an approximate typical time between infection and death of a little more than two weeks and about three weeks.

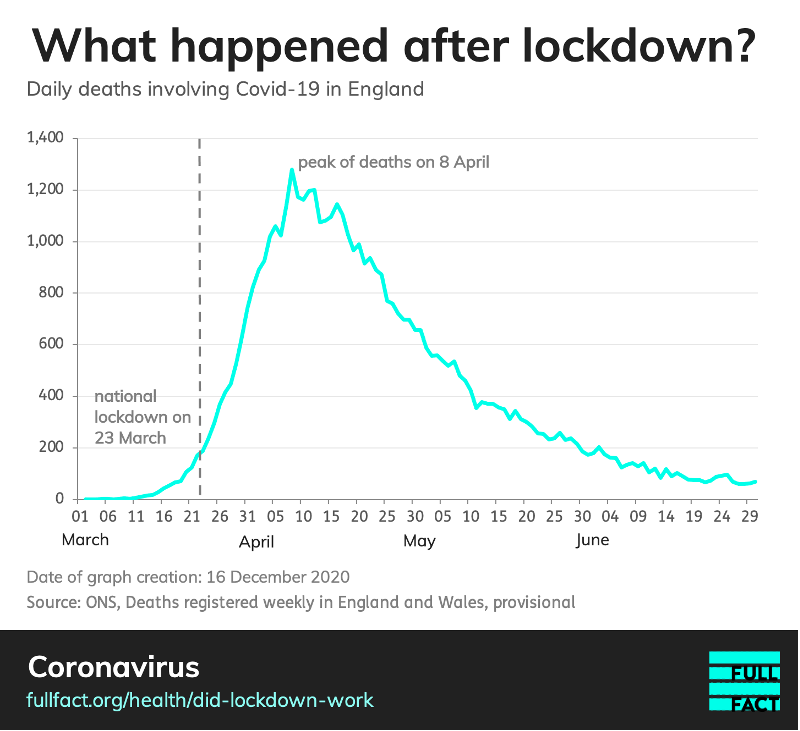

The number of people dying with Covid in England each day peaked on 8 April, which is 16 days after 23 March. This is consistent with the most obvious assumption: that the lockdown stopped the number of daily infections growing, and therefore caused the daily deaths to fall soon afterwards.

Mr Hitchens, however, has said this is impossible. “It's now pretty much accepted,” he told talkRADIO on 2 November, “that the period between infection and death... is approximately four weeks.”

The claim of a “four week” period between infection and death, rather than two or three weeks, seems to come from a blog by the editor of the Spectator, Fraser Nelson, which Mr Hitchens mentioned.

The blog says: “We now know Covid's infection-to-death timescale is closer to four weeks than two weeks,” citing statistical research (not yet peer-reviewed) by Professor Simon Wood, which infers an average time from infection to death of about 27 days, implying that daily infections began to fall before 23 March.

This research may be valuable, but it is wrong to present its conclusions as a probable fact or “generally accepted”. As Professor Wood himself says: “This paper does not prove that the peak in fatal infections in England and Wales preceded lockdown by several days.

“What the results show is that, in the absence of strong assumptions, the currently most reliable data strongly suggest that the decline in infections in England and Wales began before full lockdown.”

That reference to “full lockdown” is important, because of course the UK had tried to stop the virus spreading in other ways before 23 March. In theory, it is therefore possible that the peak of infections occurred before lockdown, as voluntary changes in behaviour, the request to work from home, and the closure of pubs and restaurants the previous Friday made some difference.

However, this is just one possibility. It certainly does not mean it was “not possible” for the lockdown announced on 23 March to cause the peak in daily infections and deaths to decline, as Mr Hitchens claimed.

Do lockdowns stop Covid, generally?

In his video of 8 September, Mr Cummins also insists that the spring lockdown did not cause the subsequent fall in deaths or severe illness. In a (now deleted) talkRADIO interview on 6 October with Julia Hartley Brewer, who shared his original video, he said: “Since April the data is pretty clear… This is real world empirical data analysed to check the effect of lockdown, and almost without exception, there is no correlation. And this is published in the Lancet, and there’s five published papers now.

“There’s essentially no substantial connection between lockdown and outcomes of ICU and mortality. That’s a reality.”

Later, he said again: “There is no credible publication post-hoc, or after the event during the summer, that has really claimed that lockdowns are in any way effective.”

This is simply untrue. A research paper published in June in Nature, one of the most prestigious scientific journals in the world, concludes: “Our results show that major non-pharmaceutical interventions—and lockdowns in particular—have had a large effect on reducing transmission.”

Another in Science in July said: “Focusing on COVID-19 spread in Germany, we detected change points in the effective growth rate that correlate well with the times of publicly announced interventions.”

Another in the BMJ said: “Earlier implementation of lockdown was associated with a larger reduction in the incidence of covid-19.”

Mr Cummins may have been referring to a research paper in one of the Lancet’s online journals in July, which said that “full lockdowns… were not associated with COVID-19 mortality per million people”. But so much research is published, especially on Covid, that it is often possible to find at least some evidence in support of almost any view.

For instance, he might instead have referred to a different paper in the same journal eight days earlier, which said: “With a tighter lockdown, mobility decreased enough to bring down transmission promptly below the level needed to sustain the epidemic.”

Some science supports Mr Cummins on some points, in other words, but a great deal—which he does not mention—contradicts him.

Was it herd immunity instead?

Mr Cummins does not deny that Covid-19 exists, or that many people died from the disease in spring. However, he claims that the epidemic began to die out naturally—soon after lockdown, but not because of it—making it appear that the lockdown itself was taking effect.

By way of explanation, Mr Cummins uses a chart showing Covid deaths per day in several European countries, which he claims shows the epidemic growing until it begins to run out of people to infect, then eventually declining to very low levels.

According to him, for a variety of reasons including prior exposure to similar viruses, most people were already immune to Covid when it first emerged, which would be why the epidemic ran out of susceptible people so quickly. In the end, he claims this meant that the pandemic in Europe was effectively over by the summer. Dr Yeadon claims something similar.

One obvious problem with this theory emerged soon after Mr Cummins made the video, when the UK and the other European countries he mentions all saw significant “second waves” of the virus. This means we can be almost certain that these societies were not immune to it.

Mr Cummins and Dr Yeadon both claim that this is a result of many “false positive” Covid tests (where people who test positive don’t actually have the virus) but, as we have said before, false positives are not common enough to explain this.

We can also now see that at the peak of the second wave in the week to 20 November, the total excess deaths in the UK were 21% (2,155) higher than the five year average. Something, in other words, was undoubtedly causing far more deaths than usual, which cannot be explained by faulty tests. This was Covid.

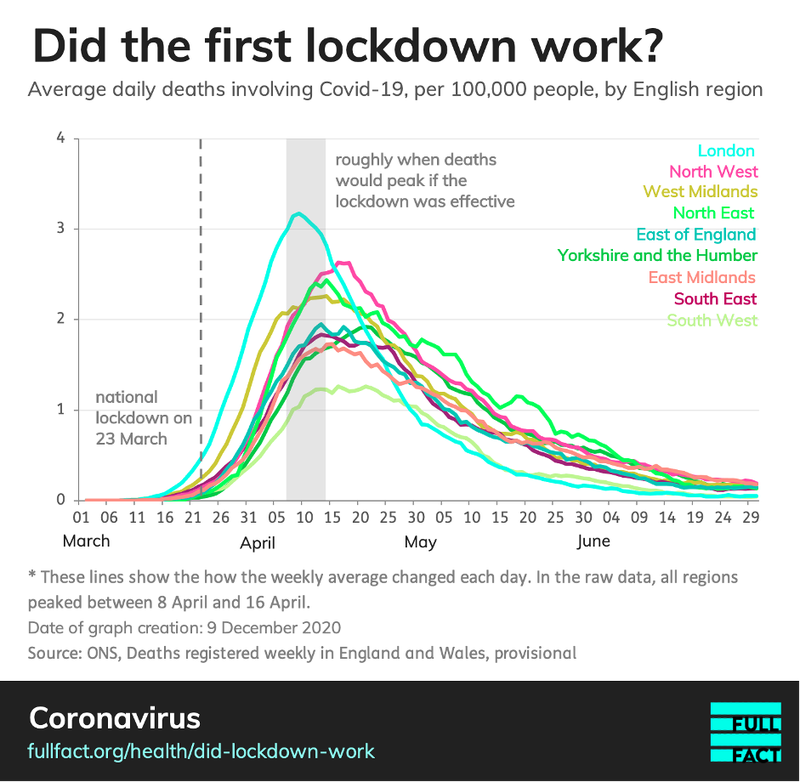

In any case, the herd immunity theory already made little sense even before the second wave. Because if the virus had already spread as widely as it could in the spring, why were some parts of the UK affected more than others?

For example, by the end of July, about 44 people out of every 100,000 living in the South West of England, had died with Covid on their death certificates. In London, however, there were 143 deaths involving Covid per 100,000 people.

If, as Mr Cummins claims, the virus infected everyone it could in London, along with everyone it could in the South West, why did more than three times as many people die?

Data from antibody surveys tells the same story, showing evidence that different proportions of the population were infected in each region. As we have said before, this also allows us to prove that much more than 0.1% of the people infected with Covid in the spring went on to die. (This was another false claim made by Mr Cummins.)

Many epidemics, with a single peak

And there is another problem. If Mr Cummins is right, and the epidemics began to decline in each region when they ran out of people to infect, and this somehow happened at different levels of infection, you would expect to see the waves breaking one after another, with the virus sweeping quickly through London, say, but taking longer to reach its peak in the South West.

If Mr Cummins is wrong, however, you would expect to see all the regional epidemics stopping almost simultaneously, when the national lockdown suddenly took effect everywhere. And indeed, when you look at the data, this is exactly what you do see—epidemics stopping at different levels of infection, but at the same time.

The Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre draws attention to this point in its analysis (not yet peer-reviewed) of the trends in intensive care unit admissions, but you can also see it in the Office for National Statistics deaths data.

As we’ve seen, if the number of new Covid infections dropped suddenly after the lockdown was announced on 23 March, then the number of new Covid deaths ought to drop roughly two to three weeks later.

We’d therefore expect to see the number of deaths peaking in all regions, no matter how badly they were affected, around the second week of April. And this is almost exactly what happened. Death certificates reveal that every English region experienced its worst day for Covid deaths between 8 April and 16 April.

The pattern is hard to see in a chart of the raw data, which fluctuates constantly, turning each curve into a messy zigzag. But if we look at how the weekly average changes day by day, the picture becomes clear.

The epidemic takes off in London first, then in the West Midlands, then in the other regions, at different speeds—before they all peak almost exactly when you would expect. We see a similar pattern of synchronised peaks at different levels in France, as demonstrated in a letter by another group of scientists, also in the Lancet.

Scepticism matters

The “lockdown sceptics” do make many claims that have some basis in science. The trouble is they are often expressed with overconfidence, or without vital context.

For example: were some people already immune to Covid before the disease emerged? Possibly they were, but it is far from clear how many people, or how well they were protected. The idea also does not seem to fit the data from some surveys of the worst affected places, which show that a large proportion of the population has been infected this year.

Still, sceptical theories can be valuable even when they are wrong—by forcing us to prove with evidence what we believe is obvious.

In this case, the idea that the spring lockdown had no effect on the UK’s Covid outbreak simply does not fit the evidence we have. It is also contradicted by a large body of scientific opinion and research.

On the other hand, it is easy to see why the mainstream view became the mainstream view. You would expect a national lockdown to stop an infectious virus spreading. Afterwards, you would expect the data to look the way it looks. The idea may be dull and disappointing, but it has widespread scientific support. Sadly, when lockdown ended, it also explains why the virus returned.

Correction 21 December 2020

This article has been corrected to say Peter Hitchens is a columnist for the Mail on Sunday, not the Daily Mail.