What was claimed

The number of deaths in England and Wales is below average for this time of year.

Our verdict

Incorrect. Over the final four weeks of 2020, the number of deaths was 16% above the 27-year average and 20% above the five-year average.

What was claimed

The number of deaths in England and Wales is below average for this time of year.

Our verdict

Incorrect. Over the final four weeks of 2020, the number of deaths was 16% above the 27-year average and 20% above the five-year average.

“We're seeing mortality that's well within the envelope of what normally happens this time of year. The last five years have been a below average number of death years if you look at the ONS data anyway compared to the last 27, which is how far their data go back...we’re below the average point of the deaths at this time of year...”

On talkRADIO, former pathology professor Dr John Lee was asked by presenter Julia Hartley-Brewer whether we are currently seeing “excess mortality”, or more people dying than usual.

Dr Lee responded by saying that mortality is currently within the bounds of what normally happens this time of year. He suggested that we should not compare this year to the five-year average (even though this is a standard practice), because he claims that mortality was especially low in the last five years.

He said that if you look at the 27-year average, we’re below the longer-term death level for this time of year.

This is not true. Using figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) for England and Wales, the death rate towards the end of 2020 was about 20% above the five-year and 16% above the 27-year average. After adjusting for population size, the death rate was still above the 27-year average, though to a lesser extent.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Dr Lee claimed that “we’re below the average point of the deaths at this time of year.” It’s unclear what he meant by “this time of year”, but whether you look at the last week, the last fortnight, or the last month of the year, the picture is much the same.

The number of deaths at the moment is above the historic averages.

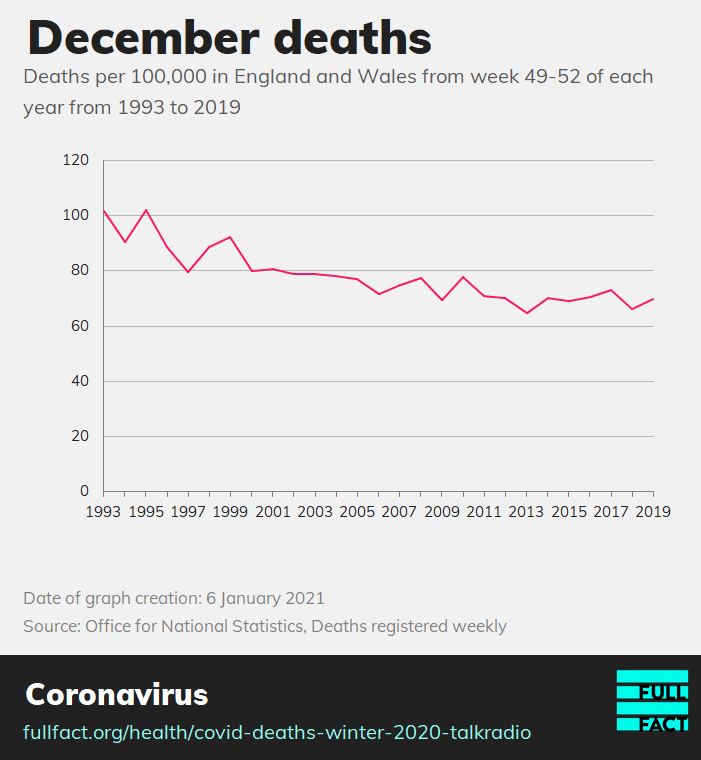

We currently have figures on the number of deaths registered in England and Wales from 1993 up to the last full week of 2020, ending on Friday 25 December. These appear to be the 27 years that Dr Lee refers to.

The number of deaths in the final four weeks of 2020 (from week 49 to week 52) was 16% higher than the average for the same period over the previous 27 years.

The ONS has warned that week 52 data is not particularly comparable to previous years, as many previous years had two bank holidays in week 52, while 2020 had only one (Christmas Day), meaning there were more days in the week where deaths could be registered. But even if we exclude week 52, the number of deaths in weeks 49-51 was still 14% higher in 2020 than the 27-year average of the same period.

Looking at the more recent past, the number of deaths registered in England and Wales in each week from week 49 to week 52 of 2020 was higher than in the corresponding weeks in any of the previous five years.

Overall, the number of deaths during this period was 20% higher than the average over the same period from 2015-2019. Excluding week 52, the number of deaths in weeks 49-51 was still 14% higher than the average over the same three weeks from 2015-2019.

While he didn’t say it explicitly, Dr Lee may have been referring to figures which adjust for population growth—something he has done in the past to make a similar argument.

Even with this adjustment, however, his claim would still be wrong.

After adjusting for population, there were 83 deaths per 100,000 people in the last four weeks of 2020, 16% higher than the average over the past five years, and 5% higher than over the past 27 years. Excluding week 52, weeks 49-51 of 2020 saw 11% more deaths per 100,000 people than the previous five-year average, and 4% more than the 27-year average.

Even if Dr Lee was referring to a different time period, the number of deaths per 100,000 people was higher in 2020 in each of the final eight weeks of the year, than the average for any of those weeks over the past 27 years.

So it’s not true that the number of deaths are currently “below average”, whichever way you cut it.

Aside from his statistics being incorrect, Dr Lee’s reasoning to discount the previous five-year average as a point of comparison is also questionable.

To suggest the entire five-year block from 2015-2019 is anomalous and incomparable because the level of deaths was lower than in previous years seems to ignore the fact that, over time, populations change, medical technology improves, public behaviour alters, and the expected death rate may well be affected as a result.

The data shows that, far from 2015-2019 being an anomaly, this period continues the pattern of death rates in the last four weeks of the year falling since the early 1990s.

The past five years are not somehow abnormal because they are different to the preceding 22 years: they are the new normal.

Indeed, the point of comparing 2020 to a five-year average, as opposed to just one year, is to allow for the fact that some individual years may well have death rates which were abnormally low or high.

Even if the death toll towards the end of 2020 had been in line with the average for the past 27 years, that doesn’t mean that would necessarily be a “normal” number of deaths.

Full Fact fights for good, reliable information in the media, online, and in politics.

Bad information ruins lives. It promotes hate, damages people’s health, and hurts democracy. You deserve better.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.