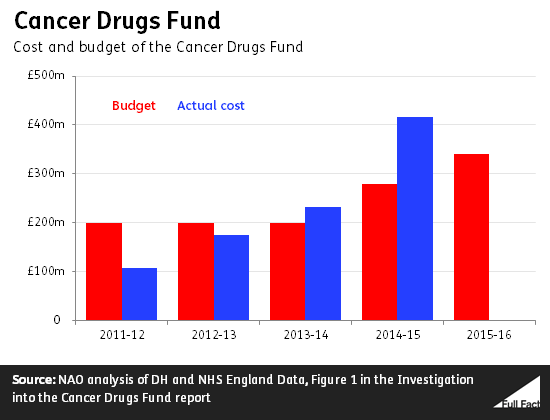

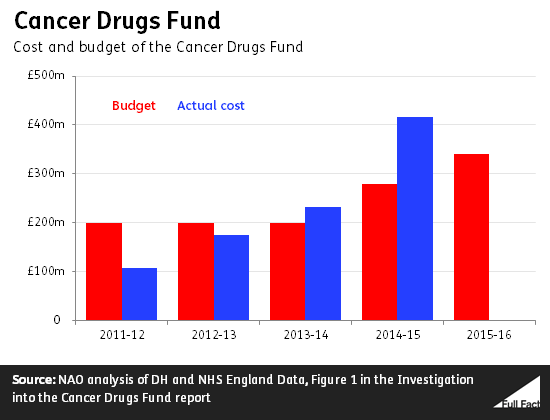

The Conservative Party's 2015 manifesto pledged to "continue to invest in our life-saving Cancer Drugs Fund". That has happened—the fund's budget is up from £280 million last year to £340 million although that was announced before the general election.

That's just the budget—in practice spending may well be higher this year. Last year the fund cost just under £420 million, according to the National Audit Office (NAO). This represented an overspend of almost 50%. NHS England expects some amount of overspending this year too, despite having removed some drugs from the scheme to rein in costs.

The Drugs Fund might not survive much longer, or not in its current form, with NHS England planning to consult on a new scheme to take its place.

The fund pays for cancer drugs that haven't been approved according to the usual process

The fund pays for cancer drugs that wouldn't otherwise be available on the NHS in England, because they haven't been approved by the regulator, NICE. Some of them haven't yet been assessed by the regulator, some of them are being assessed at the moment, and others have been assessed but were not judged to be clinically effective or cost effective enough.

There's a list of drugs routinely available through the Fund. If a patient meets the conditions for a drug on the list then the cancer specialist leading their care can apply to the fund for the treatment on the patient's behalf. Cancer Research UK advises patients that these applications are likely to be successful.

The fund also takes applications for drugs that aren't on the list, usually to treat rare conditions.

It was formally set up in April 2011 following an "interim" period of funding from October 2010. Since 2013/14 it's been overspending its budget, according to the NAO.

More than half of the spending rise came from treatment getting more costly per patient. The rest came from an increase in the number of patients. This led to drugs being taken off the list for the first time. According to the NAO this hasn't had the desired effect on spending, and that's led to the decision to take more drugs off the list.

The fund is due to be replaced, although it's not clear yet with what

It might seem callous to judge a drug to be insufficiently "cost effective". The potential for extra months or years of life may well be priceless to a cancer patient and their loved ones.

But in a health system with limited resources every decision to spend money on one kind of treatment represents a decision not to spend it on another. We can think of the cost of a cancer drug not only in cash terms but also in terms of the lives lost and suffering caused elsewhere by those conditions we may otherwise have been able to treat or prevent.

NICE assesses drugs and other treatments based on how many "quality-adjusted life years" are gained per £1 spent. Half of the people helped by the Cancer Drugs Fund have received drugs that have been assessed by NICE but not been recommended by it on the basis of the available data, according to the NAO.

Many health experts agree that the Cancer Drugs Fund hasn't been good value for money, partly because the NICE procedures are bypassed. The Independent Cancer Taskforce, which is made up of organisations ranging from the NHS and the Department of Health to Macmillan Cancer Support and Cancer Research UK, has concluded that "it is widely acknowledged that it is no longer sustainable or desirable for the Cancer Drugs Fund to continue in its current form".

It thinks there should still be a fund, but that this should only cover drugs which haven't yet been assessed by NICE or that have been conditionally approved by it.

NHS England has said it will work with NICE and other bodies to develop a new system to replace the fund.