One in four? How many people suffer from a mental health problem

- A widely-cited 2007 survey found one in four people in England experienced mental illness at various points in that year. This wasn’t the original source of the 1 in 4 figure, which goes back to the 1980s.

- The finding is regularly misinterpreted as meaning that one in four of us will suffer from a mental illness in our lifetimes.

- The 2007 study measured different conditions in different time frames so the findings can’t tell us how many have suffered from mental illness in any one of these periods.

- A more recent version of the survey found that one in six people suffered from a common mental disorder at various points in 2014.

- Separately, the Health Survey for England found in 2014 that one in four people reported having been diagnosed with at least one mental illness at some point in their lives. A further 18% said they’d experienced an illness but hadn’t been diagnosed.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

How common is mental illness?

“One in four” is widely cited in the UK as the number of people who suffer from a mental health problem.

The estimate has been around since the 1980s, although a commonly cited source for the figure is the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS). This found that 23% of people in England had at least one psychiatric disorder at some point in that year, and a third of these—7.2% of people—had more than one.

Because each condition included in the 23% figure has a different time frame it’s not meaningful to use the data to say this many are ill in every year, or in any other time period. But the findings do suggest that the number suffering over a lifetime will be more than one in four.

The figures are based on whether survey respondents met criteria that indicated certain illnesses and in some cases on follow-up interviews with medical specialists. The methods used vary by condition.

For example, to screen for Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), respondents were asked if they had experienced a traumatic event. If they had, they were asked if they had experienced any of ten symptoms, including jumpiness or difficulty sleeping, twice in the past week. Those who answered yes to six of the ten symptoms screened positive for PTSD.

Newer figures are available, but don’t cover the same thing

A more recent Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (covering 2014) was published last year. It doesn’t provide an update on the one in four figure though.

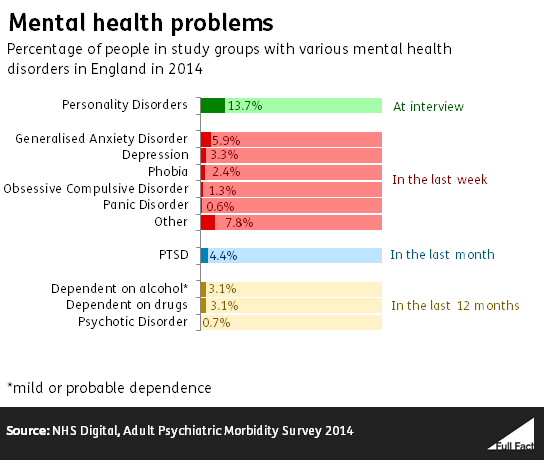

It did report that one in six people in England had a common mental disorder (CMD) in the week before they were interviewed for the study. This, according to the researchers, suggested that around this many could be expected to have a CMD at any one time. These CMDs included things like generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder and panic disorder.

Since 2000, the proportion of women recorded as having a CMD in England has increased, while in men it has stayed relatively stable.

The study also looked at a number of other conditions including personality disorders, PTSD and drug and alcohol dependency.

These figures are only estimates, as the researchers point out, and the true proportion of people with the conditions could vary from these findings. However the researchers describe the study as the “most reliable profile available of mental health in England.”

Lifetime mental illness: uncertain estimates

Because both the 2007 and 2014 surveys looked at different disorders relating to different time frames, we can’t attach a time frame to them as a whole.

But the findings from 2007 do suggest that at least a quarter of people, and probably more, will suffer from one of those illnesses in their lifetime. Although three-quarters of the study group were not found to have had any mental health conditions at any point in 2007, some will have previously been ill or will become ill later in life.

The 2014 Health Survey for England also suggests a higher lifetime figure.

It found that 26% of adults reported having ever been diagnosed with at least one mental illness. And a further 18% reported having experienced a mental illness but not having been diagnosed.

That’s based on what diagnoses people report having received, and how they view conditions they’ve had that weren’t diagnosed. There are limitations with this kind of approach because, unlike the APMS, it relies on the perceptions of the people surveyed rather than a systematic attempt at diagnosis by experts.

And, since it’s trying to measure illness experienced across the lifetimes of those surveyed, it’s only as good as the memories of its participants, and in some cases how they self-diagnose their conditions.

There’s some evidence to suggest people can tend to see mental health disorders differently to those designing the surveys. 26% of respondents to a 2013 survey of people in Scotland said they had personally experienced a mental health problem at some point in their life time.

The proportion rose to 32% when asked if a health professional had ever diagnosed them with one or more of a list of 15 different mental health disorders. That suggests some people may not have been aware of the types of conditions that fall under the umbrella term of “mental health problems”.

Other evidence on mental health

Research by David Goldberg and Peter Huxley from 1980 found that one in four people in its sample had suffered some sort of mental disorder in a year. It didn’t look at the same conditions as the APMS (so it didn’t include drug or alcohol dependence for example).

More recent data is available on the numbers who are in contact with mental health services.

But this doesn’t tell you how many people are suffering from a mental health problem, as clearly not everyone who is mentally ill will receive a diagnosis or treatment. Of all the adults who took part in the 2014 APMS one in eight reported that they were receiving mental health treatment at the time of the study.