We don’t know how many students return home after studying here, so there’s no clear evidence for this claim. In the words of the Office for National Statistics (ONS): “There are no official figures that show how many students do not emigrate and remain in the UK after their studies.”

At the moment, the available evidence is contradictory. Most student immigrants come from outside the EU on a temporary visa, and a minority still have the right to remain after a few years. Diane Abbott’s office pointed us to figures showing this via a Universities UK report, as well as a Times article showing that a small minority of students overstay their visas.

At the same time, figures showing how many former international students emigrate are much lower than the figures for students immigrating to the UK. If accurate, that indicates many more students are remaining in the UK than the visa figures would suggest.

The ONS and others are working to improve the evidence we have in this area.

International students are adding to the UK population

Even though we can’t be sure of all the figures, we do know that student immigration is adding to the UK population overall. Not all students who come to the UK return home. The challenge is measuring how many do so, and explaining what’s happening to those who don’t.

We don’t have precise answers to either question. Most statistics don’t follow individual immigrants and the routes they take through education and beyond. Our main migration estimates, for example, just look at snapshots of one set of people arriving and another set leaving.

The ONS says these main estimates provide “the only currently available data source that identifies when a student emigrates.”

On the face of it, these suggest most immigrant students aren’t actually emigrating.

In 2016, an estimated 588,000 people immigrated to the UK – that is, they intended to stay here for at least a year. Of those, 136,000 said the main reason they came was to study. At the same time, about 63,000 former student immigrants left the UK.

We can’t just compare 136,000 to 63,000 here. They’re actually from slightly different sets of data, but more significantly they’re not the same people: those 63,000 people will have been immigrants from previous years.

But that gap has been fairly consistent over the past few years. In every year since 2012 around 100,000 more student immigrants have arrived than former student emigrants have left. And each year the emigration of former students has accounted for less than half of student immigration.

So what’s happening to these students if they’re not all emigrating? The ONS offers three main suggestions:

- Students might be staying longer than expected through legitimate means, like getting extensions on their visas for further study or to move into work.

- They might be overstaying their visas, so breaking the law.

- The statistics could be missing students.

Some non-EU students extend their visas

Most student immigrants come from outside the EU on a temporary visa. They have the option to stay longer in the UK by extending their visa, either to continue study or move into a different category such as a work visa. In 2016, there were around 44,000 such extensions. That figure is falling rapidly: three years ago it was over 112,000.

By comparison the number of non-EU immigrants coming to study was estimated at about 92,000 last year, and 122,000 three years ago. Again, those figures don’t cover the same group of people, so can’t be compared directly.

Earlier this year, the Home Office also published figures tracking the journey of a group of immigrants who had arrived to the UK on a study visa in 2010 over several years.

Of those issued a study visa in 2010, nearly half saw it expire within two years, showing that many will have been on short courses. After five years, only 19% still had valid leave to remain and 1% had indefinite leave to remain.

That’s as far as these figures go – they don’t actually confirm what people do after their temporary visa expires.

A small minority are proven to overstay

For obvious reasons, we don’t know a huge amount about how many students are overstaying their visas in the UK.

Diane Abbott’s office pointed us to a Times report describing a leaked Home Office study which suggested that only a small minority of international students break the terms of their visa by staying in the UK after their course finishes.

Without seeing more detail, it’s difficult to judge the accuracy of this report. The government says the work is “not completed”.

Missing students?

These immigration figures cover students who say they intend to stay in the UK for at least a year – following the UN definition of who counts as an immigrant. That means some students aren’t counted here, for example those who come for a single year course: they arrive in September and leave the following summer. On the same basis, the emigration figures only cover students who intend to leave the UK for more than a year

That means it’s possible that some students are slipping past these particular figures. This could be because they leave the UK within a year, or because they only end up leaving the UK temporarily. However, ONS analysis suggests that neither of these possible counting methods fully explains the gap between students immigrating to the UK and former students emigrating.

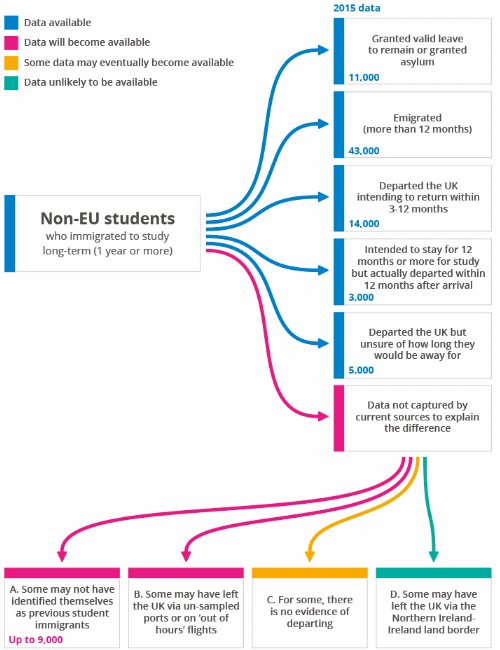

The figure below shows recent work by the ONS – using data from 2015 in this case – to visualise all the possible things that could be happening to non-EU students who’ve previously immigrated to study here.