Refugees in the UK

People sometimes use the terms “refugee” and “asylum seeker” interchangeably. But they’re different.

The UK government accepts someone as a refugee if he or she has fled their own country because of a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion”. Those words are from the Geneva Convention on refugees, a United Nations agreement that the UK is signed up to.

The government also allows people to stay in the country to keep them safe without granting them refugee status as defined by the Geneva Convention. When we refer to “refugees” or “asylum grants” in this article, we’re including these other forms of asylum, such as Humanitarian Protection or Leave Outside The Rules for human rights reasons.

An asylum seeker is someone who has applied to the Home Office for refugee status or one of those other forms of international protection, and is awaiting a decision on that application.

Join 72,547 people who trust us to check the facts

Subscribe to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

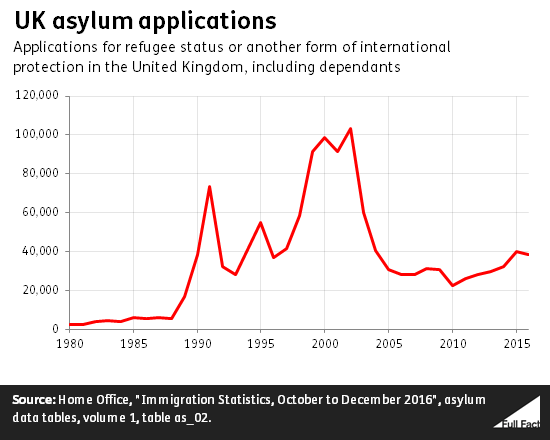

Asylum applications in the UK

In 2016, there were around 39,000 applications for asylum in the UK. That’s including dependant family members of the main applicant. Those asylum seekers are counted among the estimated 600,000 immigrants to the UK in the 12 months to September 2016, most of whom come to work or study.

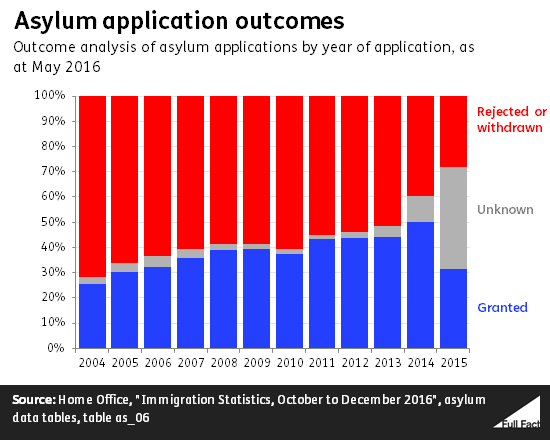

The annual success rate is more complicated than dividing 21,000 by 39,000, because of the time lag in making decisions, and because people can appeal the initial decision.

But we can say that over the past few years, excluding unknown outcomes, around half of asylum applications have ultimately been successful and the other half withdrawn or rejected.

Asylum seekers and refugees in the UK

There were 33,000 asylum applications pending at the end of 2016, again including the dependants of applicants.

There may also be asylum seekers whose claim has been rejected that join the “irregular migrant population”, as immigration policy experts refer to it. Others might call them “illegal immigrants”. It's hard to get a handle on how many failed asylum seekers are still here without permission, let alone the entire "irregular" population.

There’s no official figure for the number of refugees in the UK.

It partly depends on who you consider a “refugee”, given that people’s residence status can change over time after being granted asylum. They may start on a time-limited residence permit, move to permanent residence, through to British citizenship.

Someone who arrived here in the country as a refugee—perhaps as a child—and is now a UK citizen might or might not still consider themselves a refugee.

The UN does publish annual estimates of the refugee population, which it’s previously told us are based the number of successful refugee applications in the previous 10 years—the assumption being that after a decade, a refugee will have become a citizen and no longer needs international protection.

On this fairly uncertain method, there were an estimated 123,000 refugees in the UK in 2015. That’s around 0.2% of the population.

Where do refugees and asylum seekers come from?

Almost 90% of asylum seekers came from Asian or African countries in 2016. The top five nationalities for UK asylum applications were Iranian, Pakistani, Iraqi, Afghan and Bangladeshi.

In terms of asylum grants (before any appeal), Syrians topped the list, followed by Iranians, Eritreans, Sudanese and Afghans.

These figures don’t include over 5,000 people resettled from other parts of the world, as distinct from coming to the UK to apply for asylum (you can’t do so from another country). The vast majority of those have been Syrians.