Why do immigrants come to the UK?

- From 2010 to 2016, an estimated annual average of 495,000 non-British citizens moved to the UK with the intention of staying for 12 months or longer. An estimated annual average of 190,000 left the country to live abroad during the same period.

- Economic and labour market factors are a major driver of international migration and work is currently the main reason for migration to the UK.

- Language, study opportunities, and established networks are all factors that encourage people to migrate to the UK.

- The UK has relatively high numbers of migrants in comparison to other EU countries, but has neither the highest in absolute terms nor the biggest share of migrants in the population.

- Immigration policy is not the only policy that affects migration flows; others include policies on employment and trade, etc.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

From 2010 to 2016, an estimated annual average of 495,000 non-British citizens immigrated to the UK

There are different ways to measure immigration to the UK, and all of them have limitations. One of the most commonly used data sources is the International Passenger Survey (IPS). This looks at migration of people intending to stay for at least 12 months.

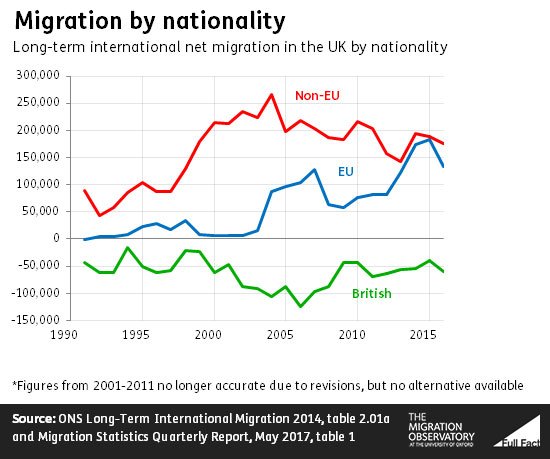

Using this measure, immigration of non-British nationals averaged at 495,000 between 2010 and 2016, and an average of 190,000 non-British nationals ‘emigrated’ (i.e. left intending to stay away for at least 12 months) each year during this period, leading to net migration of about 305,000 non-British citizens on average.

In 2016, 514,000 non-British nationals moved to the UK. This is close to the highest it’s been on record, although down compared to around 550,000 in 2014 and 2015. Recorded non-British immigration in the late 2000s was around 500,000 a year, but these figures are not reliable. They are known to have underestimated the scale of immigration to the UK. The ONS has since revised its figures for net migration, but not for immigration or emigration estimates alone.

Economic and labour market factors are a major driver of international migration

The UK’s labour market is thought to be a significant draw for migrants from both within the EU and from non-EU countries. Research suggests that economic growth and the demand for specialists in certain occupations increase demand for both high- and low-skilled labour.

Income inequality in the UK over the past decades also appears to have played a role in attracting high-skilled immigrants, because it means that these people can often command high incomes in the UK.

For low-wage jobs, the UK’s flexible labour market and a range of policies have played a role in drawing in workers from the European Union. UK immigration policies do not allow employers to bring non-EU workers to the country for low-skilled jobs.

Work is currently the main reason for immigration to the UK

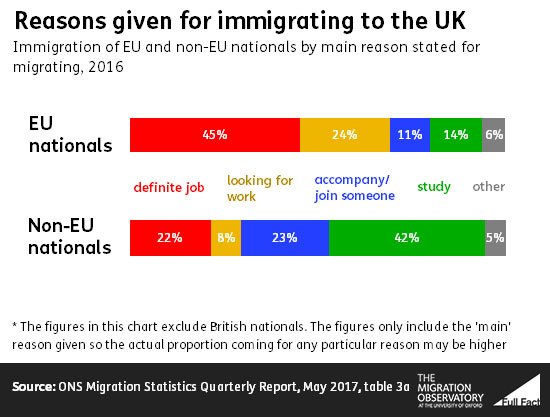

The most common reason non-British citizens reported for coming to the UK in 2016 was work. About 226,000 (50%) came for work, followed by those who came for study (124,000 or 27%). Family reasons for migrating were reported by 77,000 or 17% of migrants.

EU citizens were particularly likely to report coming for work, while non-EU citizens were more likely to report coming for study or family. Among EU nationals, citizens of new Eastern European member states recoded the highest shares of those coming for work.

A relatively large share of foreign citizens gaining permanent or long-term residence rights in the UK (just under two fifths) were classified as employment-based migrants, compared to most other wealthy countries that are members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and for which data are available. This excludes EU citizens exercising free movement rights, most of whom also report coming for work (as described above). Relatively fewer came for family reasons.

Language, study opportunities, and established networks are all factors that encourage people to migrate to the UK

The UK’s history of migration is likely to be a key contributor to current migrant inflows. Existing family and community networks in a country are thought to facilitate new migration by lowering the risks of migration and support people after they arrive. These networks can facilitate job search and lower the costs of housing and childcare. Similarly, cultural and historical links with other countries (such as former commonwealth countries) are thought to facilitate migration.

Language also plays a role. The ubiquity of English as a second language around the world is likely to be an important factor in many people’s decisions to choose the UK as a destination.

Finally, UK universities and colleges are a significant reason for international migration to the UK. The UK had the second highest number of international students after the United States according to UNESCO.

The UK has relatively high numbers of migrants in comparison to other EU countries, but has neither the highest in absolute terms nor the biggest share of migrants in its population.

One of the best available data sources for comparing migration in the UK with other EU countries is the 2011 censuses undertaken by EU member states. While this is now a few years old, other data sources do not allow the same sort of direct comparison of migrants’ characteristics. Comparable data are available for 12 EU countries that were members of the EU before 2004, including the UK.

In absolute terms, in 2011 the UK had the second highest population of foreign born people (8.0 million) after Germany (11.3 million). The UK also had the third highest population of foreign nationals (5.1 million) after Germany (6.1 million) and Spain (5.2 million).

Because the UK is one of the EU’s most populous countries it is perhaps not surprising that it has a larger number of migrants than smaller member states. The share of migrants in the population can be a more useful measure than absolute numbers when looking at the role of migration in a given country.

Among the 12 old EU countries for which comparable data are available, the UK had the fifth highest share of foreign born (13%) in its population in 2011 and the fifth highest share of foreign nationals (8%) in its population. Luxembourg, Ireland, Germany and Sweden all had higher shares of foreign born people than the UK.

Looking only at foreign nationals (and thus excluding naturalized citizens), Luxembourg, Ireland, Spain and Greece had a higher share than the UK. Countries with a lower share of both foreign born people and of foreign nationals in 2011 included France, the Netherlands, Denmark, Italy and Portugal.

Immigration policy is not the only policy that affects migration flows; others include policies on employment, welfare and trade (among others)

Shifts in immigration policy can alter the scale and composition of migration inflows and outflows by affecting who is eligible for a visa to come to the UK or to settle here. However, the relative importance of policies in affecting the number of migrants and in explaining changes over time has been debated.

Immigration flows often fluctuate in the absence of significant changes in policies. The increase in EU immigration between 2010 and 2016 is one example of this. The UK’s economic recovery is likely to have played a role in both cases.

Research has pointed to several other policies that affect immigration flows in addition to immigration policy. These include areas such as labour market regulation, macro-economic policies, and trade. Because these policies affect employers’ recruitment practices and the market in which they operate, they result in higher or lower demand for certain groups of workers, including newly arriving migrants.

More information

- Migration Observatory briefing -Long–Term International Migration Flows to and from the UK

- Migration Observatory briefing -Migrants in the UK: An Overview

- Migration Observatory briefing -The Labour Market Effects of Immigration

This briefing was originally written by Yvonni Markaki from the Migration Observatory in collaboration with Full Fact for the 2015 general election, funded by the Nuffield Foundation. It has since been updated by Zovanga Kone and Yvonni Markaki.