Counter-terrorism powers

Terrorist attacks in London and Manchester in recent months have killed at least 34 people.

The attacks have been widely condemned both at home and abroad. They have also led to political questions about what, if anything, the state should do differently to protect its citizens from terrorism.

At the moment, someone suspected of terrorism can be arrested and held for up to 14 days before being charged. A lot of changes have been made to the anti-terror laws, which have given the police the means to charge criminals for additional offences—such as possessing information for terrorist purposes.

There were 183 people in prison for terrorism-related crimes at the end of last year.

Criminal convictions require evidence. When evidence for a criminal conviction is not available, the law allows or has allowed other counter-terrorism powers to control people suspected of terrorist intent, including:

- Currently, TPIMs—Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures, which restrict what a suspect can do

- Before TPIMS, Control Orders, which were more restrictive

- In the 1970s in Northern Ireland, internment

All of them strike different balances between liberty, safety, and security.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

What is internment?

Internment means imprisoning people without trial.

The idea behind internment is to detain people when the police don’t have enough evidence to charge them, but strongly suspect them to be involved in terrorism.

Supporters of internment have focused on the 3,000 “jihadi extremists” it's frequently reported that the security services have said are under active investigation by the security services. It is impossible to corroborate those reports.

In Northern Ireland, in the early 1970s, the decision to intern someone “suspected of acting, having acted or being about to act in a manner prejudicial to peace and order” was taken by a government minister on the advice of the police. The courts had limited powers to intervene.

Did internment make things worse in Northern Ireland?

That seems to be the consensus, although the situation in Northern Ireland 40 years ago was arguably different in a number of ways. The number of organised murders was higher than in Great Britain today. Northern Ireland saw protests, street violence and general civil unrest as well as violence from and between different terrorist groups.

Another difference is that both sides in the Troubles had political objectives and organisational structures that were fairly well defined, opening the possibility of peaceful negotiation and compromise. It’s hard to be sure how relevant that experience is to recent attacks.

Almost 2,000 people suspected of involvement with paramilitary terrorist groups were imprisoned without trial in Northern Ireland between 1971 and 1975. It didn’t reduce the level of violence.

“While internment in itself provided limited, if any, security benefits, the social and political reaction which internment created far outweighed this. As a result violence increased for the rest of the year… the main winners from the introduction of internment were the Provisional IRA”. That’s according to historians Paul Bew and Gordon Gillespie. Other academics agree, as did members of the armed forces based in Northern Ireland during this period.

The Home Secretary at the time, Merlyn Rees, said that “for every person who is detained, like dragon's teeth, someone else joins the organisation… detention does not solve the issue”.

Internment was accompanied by the ill-treatment of some prisoners and was seen as badly executed in practice, so it’s possible that it might have been more effective if carried out differently. Professor Richard English points out that in previous periods the authorities had found internment to be an effective way of dealing with the IRA, when it was in force in the Republic of Ireland as well.

TPIMs

TPIMs stands for Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures. TPIMs place various restrictions on where people can go and what they can do. Suspects can be ordered to observe an overnight curfew, or surrender a passport, or wear an electronic tag.

TPIMs can be given for up to two years as a “last resort” to protect the public from people “whom it is feasible neither to prosecute nor to deport”, in the words of the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation (then David Anderson QC).

They’re only allowed if the Home Secretary “is satisfied, on the balance of probabilities, that the individual is, or has been, involved in terrorism-related activity”—along with four other conditions: there has to be new activity, the restrictions must be necessary to both to protect the public and to restrict the person's involvement with terrorism, and there must be either court approval or no time to get it.

Do they work?

TPIMs certainly aren’t widely used. The intelligence services may see them as less useful than the more restrictive Control Orders that they replaced.

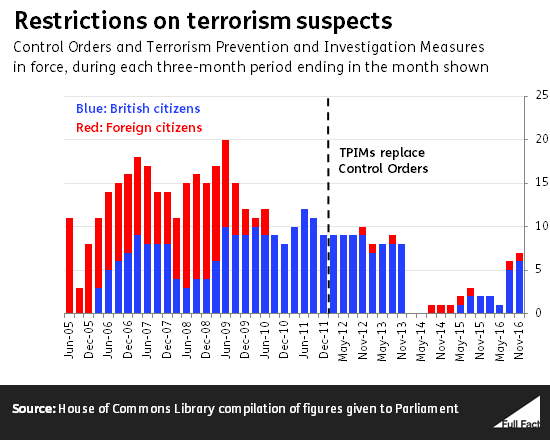

“In practice TPIMs may be withering on the vine as a counter-terrorism tool of practical utility”, a committee of MPs and Lords reported in January 2014. For most of that year, only one person was under a TPIM (on and off). But the use of TPIMs has been on the increase more recently—there were seven in force as of 30 November 2016.

Mr Anderson says that TPIMs are “as stringent as anything available in a western democracy”, and following tweaks over the years “have provided an effective way of dealing with a small number of terror suspects against whom it has not been possible to deploy the UK’s well-stocked armoury of criminal offences”.

What happened to Control Orders?

Control Orders, introduced in 2005, allowed the Home Secretary more power over the lives of suspects. They could be renewed indefinitely if deemed necessary. Curfews were longer. And people could be banned from using mobile phones and the internet completely, in addition to the restrictions that are possible using TPIMs.

Control Orders were effective at disrupting terrorism, according to Mr Anderson (and his predecessor). But he acknowledged the “unsettling” nature of the powers they gave the government, and civil liberties campaigners criticised them.

Politically, the Liberal Democrats were also against Control Orders, and were able to negotiate their replacement with the less onerous TPIMs when they joined the Conservatives in a coalition government in 2010.

But some features of Control Orders have been put back into TPIMs in the past few years. Perhaps most significantly, the Home Secretary has regained the power to force a suspect to live in a particular place, so long as it’s within 200 miles of their home.

Update 6 June 2017

We added comments made by David Anderson on the effectiveness of TPIMs in a letter in today's Times. We also added further detail on the differences between Control Orders and TPIMs.