Why are more people using food banks?

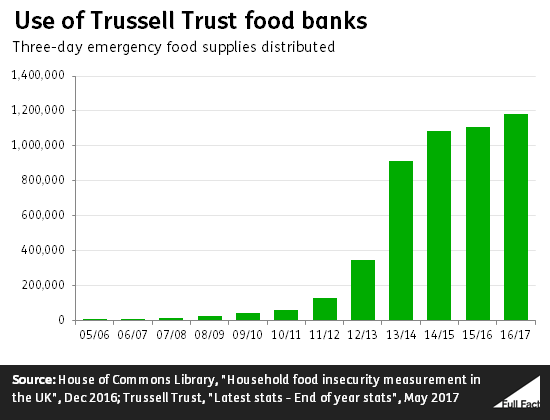

According to statistics published by the Trussell Trust (the UK's largest network of food banks) the use of their services has risen dramatically over the last decade or so.

In 2005/06, fewer than 3,000 food supplies were provided by the Trussell Trust. In 2016/17 the number of parcels handed out was almost 1.2 million.

As we’ve discussed in previous factchecks, what the Trussell Trust figures tell us about food bank usage across the UK is limited.

The statistics show the number of emergency food supplies given out by the Trussell Trust, not the number of people that have used a food bank. If someone received two parcels in a year, they were counted twice. If someone went to a food bank not run by the Trussell Trust they weren’t counted at all.

That aside, the figures from the Trussell Trust raise the question: what’s causing this surge in the use of food banks?

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

It’s useful to first think about how Trussell Trust food banks work

To receive an emergency food parcel from the Trussell Trust you have to have a food voucher issued by a doctor or social worker or someone similar. People working in Jobcentres can signpost people to a Trussell Trust food bank but they can’t make a direct referral (although the Trussell Trust told us this isn’t quite the case in practice).

Supply versus demand?

The Trussell Trust has been running for 20 years and in that time their network of food banks has grown from 1 to 427. It seems logical that more food banks will equal more emergency food supplies handed out. That does make some sense but the link between supply and demand is not always as clear as that.

It’s possible that in areas where a new Trussell Trust food bank has opened, people there were always in need of emergency food but that need was not being met. It’s also possible that changing circumstances other than the opening of a food bank could have caused the demand to rise in an area.

A 2014 report for the Department of Environment Food and Rural Affairs suggested that growing demand may be driving growing provision, rather than the other way around. But the report does highlight that at the time available good evidence was limited.

The use of food banks increased in areas where there had previously been food banks

A 2015 study by researchers from Oxford University controlled for the effect of new food banks by only looking at the usage of existing food banks. They found that in those areas between 2011 and 2013 the number of parcels handed out rose from 0.69 per 100 people to 2.2 parcels per 100 people.

Increased supply has also increased awareness

The Trussell Trust’s growing network of food banks and corporate partners could be helping them better reach people in need. For example before 2011 staff in Jobcentres did not signpost people to food banks. People visiting Jobcentres might now hear about a food bank whereas in the past they did not. The same could be said for awareness among doctors or teachers and so on.

But why people are using food banks?

In 2016/17 over 40% of Trussell Trust referrals were due to some form of problem with a benefit payment. Some of this was people whose benefit payment was delayed; others were due to changes in benefits. Another 40% were due to what we might think of as classic signs of poverty, like low incomes, debt and homelessness. The remaining referrals were due to other reasons like sickness or domestic abuse.

A study of seven food banks across the UK found that in most cases, food bank use is “the result of an immediate income crisis”. The study—produced by Oxfam, Child Poverty Action Group, the Church of England and The Trussell Trust—said that food bank use solely down to on-going low income, without a particular identifiable event, was less common.

Some of these problems could be getting more acute

Studies have highlighted changes to benefits and the use of benefit sanctions as driving increased demand for food banks.

A recent study by the University of Oxford looking at data from 259 local authorities found that when the rate of sanctioning went up in an area, the rate of food bank use also went up. When the rate of sanctioning went down, the rate of food bank use was also found to go down. This was after accounting for things like how long food banks had been open for, and the capacity of food banks.

Proving cause and effect is hard, especially when looking at such a complex topic. The government has said this report doesn’t provide “evidence of a causal link”. The report doesn’t say or prove that sanctions are the only cause of food bank use, but the researchers do say it demonstrates a “strong, dynamic link” between the two.

A Trussell Trust report suggests that the roll out of the new Universal Credit benefit has affected the use of its food banks. The Trust says that it has seen a 17% rise in food bank use in areas where Universal Credit is fully operational, citing waiting times for claimants to be assessed and difficulties with the Universal Credit system.

Trussell Trust food bank managers also cite administrative delays with benefits, and other related problems as a major driver of demand.

We still don’t really know enough about food bank use to draw strong conclusions

We don’t know enough about food bank use to fully understand what’s causing it to rise at the moment. Researchers can only rely on limited amount of data collected by the Trussell Trust to base their conclusions on.

So what’s causing the surge in food bank use? Of course, more food banks is a big part of it, meeting demand that may have existed before they arrived. There is also good evidence that changes to the benefit system have played a part in pushing up use of food banks, as well as more factors like low incomes and debt. What’s very hard to do is to say how much of the increase is down to each of these.