Framework for Information Incidents

About the Framework for Information Incidents

Since 2020, Full Fact has been working with internet companies, civil society and governments to create a new shared model to fight crises of misinformation. The Framework for Information Incidents is a tool to help different actors to identify incoming information crises and collaborate with others to respond effectively.

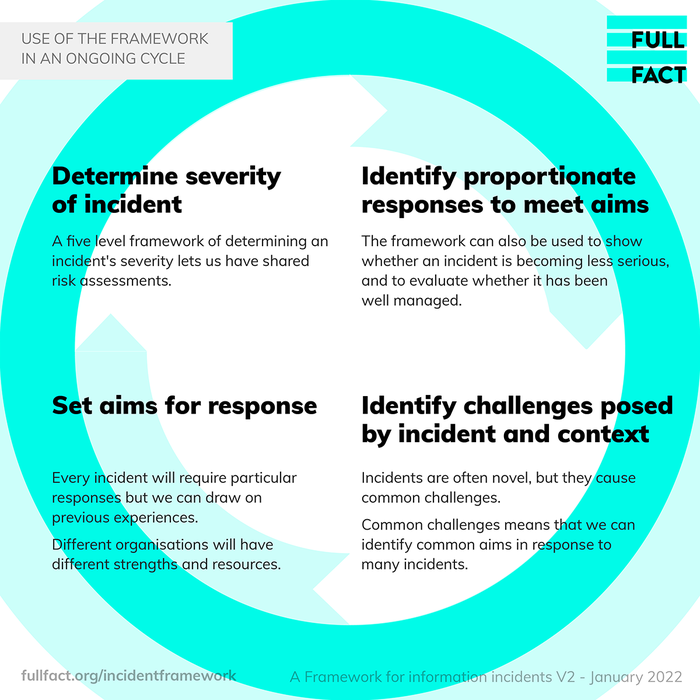

The Framework guides users to judge how severe an information incident is within five levels of severity, and to identify the challenges presented by the situation. It then guides users in thinking through possible collaborative aims and responses which are proportionate to severity in order to create a response plan.

The Framework is intended to be used on a voluntary and open basis, supporting collaboration between counter-misinformation actors from the technology sector, government, civil society, official information provision, the media, and others. It is designed to be flexible for different situations and users, and adaptable to the ever-shifting nature of misinformation and disinformation.

Why do we need a framework for information incidents?

We know that certain events can affect the information environment. That could be by increasing the complexity of accurate information, by creating confusion or revealing information gaps - all of which can result in an increase in the volume of misinformation. This was clearly evident in 2020 during the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, which prompted a slew of intensified measures from internet companies, governments, media, fact checkers, academics and civil society to try to tackle the huge amount of misinformation about the virus.

The subsequent responses showed how fast and innovatively those working to analyse and counter misinformation can respond. But it has also thrown light on the need for greater discussion of the principles behind such measures, of what proportionality means, and on the use of evidence. This is important for responding to other types of information incidents that may be just round the corner.

Analogous frameworks are used in mature industries such as cyber security, or emergency responses from public health bodies and governments.[1]

We usually refer to ‘misinformation’, but this framework is intended to also cover disinformation and malinformation as defined in Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan’s 2017 Information Disorder report.[2]

Who is the Framework for?

The Framework is for decision makers as well as practitioners. It is intended to help decision-makers understand, respond to and mitigate information crises in proportionate and effective ways. Meanwhile, for those working to respond to information incidents on the front line, we hope that the Framework will enable more effective and meaningful collaboration, for example sharing information during and in the run up to incidents, joint planning and evaluation, or increased sharing of capacity and resources.

What is an information incident?

An information incident is a cluster or proliferation of inaccurate or misleading claims or narratives, which relates to or affects perceptions of or behaviour towards a certain event or topic happening online or offline. This can occur suddenly, or have a slow onset.

The cyber security industry uses the term ‘information incident’ primarily to describe disinformation campaigns, whereas this Framework requires a definition which encompasses accidental or well-intentioned sharing of false information (misinformation), as well as intentional or hostile sharing of false information (disinformation).

Certain events are likely to trigger information incidents, and to have a substantial and material impact on the people, organisations, and systems that consume, process, share or act on information – toward good, neutral or bad outcomes. These are listed below.

An unexpected incident like a terrorist attack is likely to lead to an increased demand for information and news, but there is often a gap before information is confirmed which may lead to a surge in false information or conspiracy theories. An election might spur polarisation or prompt high profile false claims from figures in authority who are usually trusted by mainstream audiences. In both these scenarios, the baseline information environment shifts: information might be complex, incomplete, or shared or consumed in new ways – both deliberate and accidental.

Situations where incidents are likely to occur

We have identified eight categories of events or situations that might trigger information incidents that require responses above and beyond ‘business as normal’. These categories are not part of the Framework methodology, but are included here to illustrate situations where one could reasonably expect the information environment to be affected.

- Human rights or freedom of expression abuse. Information incidents might occur during disrupted peaceful protests; violent public confrontations; long term escalating tension e.g. between regions; mass detainment and/or killings; citizenship or demographic changes.

- Human violence. Information incidents often occur after a deliberate attack, and when there are high levels of death or displacement of people.

- Global or regional conflict. Information incidents may occur during wars or periods of intense fighting.

- Ongoing hybrid warfare and disinformation campaigns. Information incidents may have peaks or moments of intensity that constitute an information incident. Some citizens or audiences may experience this on a near-constant basis.

- Nationally significant political or cultural events. Information incidents are likely to occur where there is an opportunity to exploit polarisation, such as religious holidays, war memorials or commemorations, national or regional votes. Challenges may vary depending on the country’s democratic stability.

- Infrastructure and economic crises. Information incidents such as major transport disasters and accidents like explosions; shortages of gas, fuel or food; some hacks and leaks or data dumps; a run on banks, rate fixing and shorts.

- National/regional health emergencies including pandemics and epidemics. Also known as an infodemic, a term used by the WHO.[3]

- Natural or man-made environmental disasters or crises. Information incidents might occur around extreme weather, manifestations of man-made climate change such as forest fires, and natural events like eruptions and tectonic activity.

Sometimes multiple events will contribute to the same information incident (e.g. where there is war or conflict there may also be human rights abuses). Multiple incidents might occur at the same time, especially relating to long-term (perhaps polarising) issues such as climate change.

Determining the severity of an incident

Not every information incident is equally severe, and judging severity is, at least to some degree, subjective. The Framework offers criteria for determining severity so that different actors can approach a conversation on the basis of shared understanding and bring evidence to the table to justify judgements.

This framework proposes a five level system, ranging from business as normal at Level 1, where (in an open society) some misinformation will be circulating, to Level 5, which should rarely occur and requires maximum cooperation and response when it does.

Incidents might move between levels over time, either escalating or de-escalating and coming to a close. Responses can be adapted accordingly: measures put in place for an incident at Level 4 are likely to be unsuitable or disproportionate for the same incident when it is at Level 2. It may not be clear from the outset how long an incident will last, so building in review periods is important.

Level 1

A realistic scenario where there are low levels of misinformation. Long-term resilience building and future preparation is the focus of collaborative work, and additional responses are not needed on top of day-to-day activities.

Level 2

An incident might be emerging, and there is time to discuss what additional responses might be needed if the situation escalates, while monitoring the situation. The emerging incident may be resolved with light touch responses before it becomes worse.

Level 3

An incident is occurring, and it is time to put in place responses discussed earlier on. Some incidents have a rapid onset, and collaborative or individual responses will need to be put in place as quickly as possible.

Level 4

A severe incident is occurring or a less severe one is becoming more serious: stringent responses are needed to contain the crisis, or existing responses need to be adapted or additional ones introduced in line with the increasing severity.

Level 5

An incident is occurring which is rare in its severity and high impact, requiring maximum collaboration and response levels. Level 5 incidents are unlikely to be resolved in the short term.

Criteria for determining severity

The table below summarises the criteria used in the Framework to determine the severity of an information incident.

|

Severity |

Level 1 Business as normal, no additional response needed |

|

Engagement |

There are spikes of engagement and views around certain events, topics or locations but low engagement with relevant content overall |

|

Appearance across social media platforms and messaging services |

Individual false claims or narratives are not spreading across platforms |

|

Appearance on mainstream media |

False claims or narratives have not been repeated by mainstream news or discussion shows |

|

Languages |

False claims or narratives are not spreading across regions and languages |

|

Hashtags |

Hashtags shared alongside false claims and narratives are not popular |

|

Search trends |

No visible search trends |

|

Influential sharing |

Accounts sharing false claims and narratives do not have large followings |

|

Coordinated behaviour |

There is no evidence visible of coordinated behaviour |

|

Impact on behaviour |

There is no evidence the information is affecting behaviour on or offline |

|

Harm |

Information has potential to cause one significant or several less significant types of harm including to psychological wellbeing, health or life, income or economy, discrimination, safety and access to services, political processes, or distorting policy debates |

|

Effect on resources |

There is space and time to work on long-term goals such as audience resilience and media literacy |

|

Severity |

Level 2 Monitor and prepare external facing responses |

|

Engagement |

There are spikes of engagement and views around certain events, topics or locations but low engagement with relevant content overall |

|

Appearance across social media platforms and messaging services |

There are multiple false claims or narratives on one or more platforms, but spread is slow |

|

Appearance on mainstream media |

False claims or narratives have not been repeated by mainstream news or discussion shows |

|

Languages |

False claims or narratives are not spreading across regions and languages |

|

Hashtags |

Hashtags shared alongside false claims and narratives are not popular |

|

Search trends |

No visible search trends |

|

Influential sharing |

Accounts sharing false claims and narratives do not have large followings |

|

Coordinated behaviour |

There is no evidence visible of coordinated behaviour |

|

Impact on behaviour |

There is evidence the information is affecting the behaviour of a small number of people |

|

Harm |

Information has potential to cause one significant or several less significant types of harm including to psychological wellbeing, health or life, income or economy, discrimination, safety and access to services, political processes, or distorting policy debates |

|

Effect on resources |

Resources may be diverted to monitor trends but this does not have a significant impact on day-to-day work. There is time to put plans in place to mitigate the growth and effects of misinformation |

|

Severity |

Level 3 An incident is occurring, responses begin |

|

Engagement |

Relevant content has significantly higher velocity, views or engagement than comparable content would typically have |

|

Appearance across social media platforms and messaging services |

There are multiple false claims or narratives on one or more platforms spreading fast |

|

Appearance on mainstream media |

False claims or narratives have not been repeated by mainstream news or discussion shows |

|

Languages |

False claims or narratives are not spreading across regions and languages |

|

Hashtags |

Several popular hashtags are being shared alongside false claims and narratives |

|

Search trends |

Low ranking search trends for keywords related to false claims |

|

Influential sharing |

There are several influential accounts/pages sharing false claims and narratives (or accounts with high reach in a specific community being targeted) |

|

Coordinated behaviour |

There is evidence of coordinated behaviour with growing traction |

|

Impact on behaviour |

There is evidence that the information is affecting the behaviour of a growing number of people |

|

Harm |

Information has potential to cause several significant or several less significant types of harm including to psychological wellbeing, health or life, income or economy, discrimination, safety and access to services, political processes, or distorting policy debates |

|

Effect on resources |

Day-to-day work may be temporarily put on hold to tackle sudden proliferation of misinformation, but proliferation expected to tail off quickly |

|

Severity |

Level 4 An incident is occurring, coordination and responses ramp up |

|

Engagement |

Relevant content has significantly higher velocity, views or engagement than comparable content would typically have |

|

Appearance across social media platforms and messaging services |

There are multiple false claims or narratives spreading fast on all major platforms and new claims quickly gain traction |

|

Appearance on mainstream media |

False claims or narratives have been repeated by mainstream news or discussion shows |

|

Languages |

False claims or narratives are spreading across regions and languages |

|

Hashtags |

Many popular hashtags are being shared alongside false claims and narratives |

|

Search trends |

High ranking search trends for keywords related to false claims |

|

Influential sharing |

There are many influential accounts/pages sharing false claims and narratives (or accounts with high reach in a specific community being targeted) |

|

Coordinated behaviour |

There is evidence of coordinated behaviour with strong traction |

|

Impact on behaviour |

Multiple instances recorded of the information affecting people's behaviour |

|

Harm |

Information has potential to cause several significant or several less significant types of harm including to psychological wellbeing, health or life, income or economy, discrimination, safety and access to services, political processes, or distorting policy debates |

|

Effect on resources |

Day-to-day work may be temporarily put on hold in order to implement internal response plans and to enable collaboration with other organisations, including sectors which do not focus on tackling misinformation |

|

Severity |

Level 5 Maximum response levels and co-operation required |

|

Engagement |

Relevant content has exceptionally higher velocity, views or engagement than comparable content would typically have |

|

Appearance across social media platforms and messaging services |

There are multiple false claims or narratives spreading fast on all major platforms and new claims quickly gain traction |

|

Appearance on mainstream media |

False claims or narratives have been repeated by mainstream news or discussion shows |

|

Languages |

The incident is global or affecting multiple regions and languages, with the same false claims often appearing in different languages |

|

Hashtags |

Numerous popular hashtags are being shared alongside false claims and narratives |

|

Search trends |

Multiple high ranking search trends for keywords related to false claims |

|

Influential sharing |

There are numerous influential accounts/pages sharing false claims and narratives (or accounts with high reach in a specific community being targeted) |

|

Coordinated behaviour |

There is evidence of coordinated behaviour with strong traction |

|

Impact on behaviour |

Multiple instances recorded of the information affecting people's behaviour |

|

Harm |

Information has potential to cause several significant or several less significant types of harm including to psychological wellbeing, health or life, income or economy, discrimination, safety and access to services, political processes, or distorting policy debates |

|

Effect on resources |

Response is likely to dominate activity for some time, and collaboration is at a maximum, including with organisations which do no focus on tackling misinformation |

Deciding on a level: FAQs

A few of the reasons to have a shared framework include to improve coordination, establish shared language and promote cohesive approaches. From that perspective, it is beneficial for different organisations to agree together on the level of an incident. However, this may not happen, and differences of views might be legitimate and justifiable.

What happens if people don’t agree?

The severity criteria are deliberately non-numerical in order to accommodate different users - for example what is considered a large number of shares in Germany is likely to be different in Croatia due to the difference in population size. However, the criteria have been designed to be specific so that disagreements are kept concrete. Users can also develop benchmarks for use in their own contexts.

Who’s ultimately responsible?

Most users are likely to find it unacceptable or inappropriate for one or multiple organisations to impose a decision on others. In particular, respondents to our consultation in 2021 were clear that governments should not declare a level for others. Even in countries without concerns about political dynamics or government being involved in the information flows, a government declaring a level might undermine the action of others and their distinct roles (or perceptions around this). During the consultation we also heard that technology companies have not yet proved themselves credible to lead a decision-making process like this.

What if some entities don't want to join in?

A cross-sector group would ideally decide on an incident’s severity level, including representatives from civil society such as fact-checkers, local and national government (or former government representatives), press and media, relevant experts and academics and the tech industry. We have aimed to create something flexible to balance operability with commitment to meaningful collaboration and joint action. However, this is ultimately a voluntary framework that requires some trust and openness among participants in order to work: no one can or should be forced to join.

Examples of information incidents

Level 2: 5G conspiracies, UK, April 2019

When conspiracy theories about 5G technology in the UK first began to emerge in April 2019, Full Fact highlighted a distinct lack of official guidance that properly addressed public concerns.[4] Claims and narratives suggest that 5G is harmful because signals are more powerful than those that preceded it, e.g. flocks of birds dying, councils cutting down trees that had been harmed, workers wearing hazmat suits to install technology. Level 2 characteristics included:

- False claims and narratives breaking out about safety of 5G on one or more platforms, but not spreading fast/wide or across language - limited to niche communities

- Low activity around hashtags

- Potential for harm in the future (e.g. distrust of government on public health), but no immediate threats to public health and safety

- No significant impact on resources, time to put plans in place if situation escalates

Public health information about the safety of 5G rollout was not improved at the time when Full Fact identified this emerging incident.[5] As a result we saw it increase in severity: 5G conspiracy theories merged with coronavirus ones in early 2020, attracting celebrity endorsements and leading to the vandalisation of phone masts. At this point we would have classified the 5G conspiracies as a Level 3 incident, particularly as the conspiracies online translated into offline activities. We saw enhanced collaboration between organisations as the UK government, health bodies and mobile infrastructure companies created new materials on the safety of 5G and the internet companies worked to promote that information on their platforms. Many news outlets also ran explainer pieces debunking the conspiracy.

Level 3: Notre Dame fire, France, April 2019

The Notre Dame church in Paris catching fire in April 2019 almost immediately prompted false claims that the fire was deliberately started, that the chant “Allahu Akbar” was heard at the church and that a Yellow Vest protester was seen in a tower.[6] Authorities quickly suggested the fire was accidental, relating to a refurbishment. This lack of malicious cause, although accurate, left a vacuum for conspiracy theories and hate narratives aimed at non-Christians, particularly Islamophobic narratives. Level 3 indicators included:

- High engagement with and views of content related to the fire, some related content with unusually high velocity

- Minority groups being targeted with hate groups and misinformation

- Claim clusters and/or narratives are appearing across multiple platforms

- Day-to-day work temporarily put on hold to tackle sudden proliferation of misinformation, but proliferation expected to tail off quickly

Organisations moved quickly to share the information that the authorities released about the true cause of the fire, but it took a significant amount of time for that information to permeate given the amount of misinformation online. Some continued to believe the conspiracy theories: in November 2019 a French man set fire to a Mosque and shot two Muslim men. He told investigators it was an act of revenge for the Notre Dame fire [7].

Level 4: Afghan refugee crisis, Turkey, August 2021

In August 2021, public debate in Turkey about the ongoing migration flow into the country flared up as Afghans fled the advance of the Taliban. Afghan migration was already a sensitive subject among Turkish society following high immigration of this migrant group to Turkey between 2011-2019. In this context, visual materials circulated on social media during the US and NATO withdrawal contributed to information disorder, with people on social media blaming the West for allowing Turkey to be “invaded” by refugees. Level 4 indicators at the time included:

- An attempted pogrom against refugees taking place in Ankara on 11 August, fuelled by misinformation and hate speech targeting Syrians[8]

- Velocity of both true and false online content on Afghanistan and Afghan migrants in Turkey was much higher during this period

- A nationalist politician with 1 million+ social media followers, who previously shared misinformation on Syrian refugees, also shared anti-Afghan content

- Hashtags which became commonly used included #AfganlarıAlmayın (don’t take Afghans), #Afganlar (Afghans), #istila (invasion), #işgal (occupation)

- Day-to-day work was temporarily put on hold in order to plan a specific response to this crisis

Fact checking organisation Teyit called a staff meeting to tackle the increased demands from its audience and to systematise its editorial prioritisation specifically for fact checks related to the crisis.[9]

Level 5: Beginning of global Covid-19 pandemic, February 2020

This is the only incident to date we would classify as a Level 5. As well as global lockdowns and economic crises, the pandemic prompted a slew of measures attempting to grapple with newly challenging types and extremely high volume of life- and health-threatening misinformation. The characteristics that put this incident at the most severe level include:

- Relevant content has exceptionally high velocity, views or engagement than comparable content would typically have

- Misinformation is present on all major platforms and may be mentioned by mainstream news or discussion shows

- The misinformation is and may continue to result in physical harm to individuals or groups, and compound existing conspiracy theories

- Response is likely to dominate the activity of those working to counter misinformation for some time

The response to this was immediate but was, at the beginning, inconsistent, uncoordinated and required many organisations to create new emergency procedures and work internationally at a scale not seen before. Particularly as it became clear the incident was here for the long term, organisations had to reconsider protocols, funding structures, the deployment of resources and response policies.

What common challenges exist across incidents?

Every incident is unique. But in many cases, common or predictable challenges will emerge for those trying to find and distribute reliable information, or reduce the harm done by bad information.

Below is a table of common challenges that occur across different incidents. Often an incident will present more than one challenge, and incidents might cross over with one another, causing multiple challenges at the same time.

|

Challenges across different incidents |

|

1. Threats to freedom of expression e.g. when there is:

|

|

2. Unclear or quickly changing situation e.g. when there is:

|

|

3. Difficulty disseminating or communicating information e.g. when there is:

|

|

4. Information vacuums and uncertainty e.g. when:

|

|

5. Damaging behaviour by influential public figures or authorities e.g. when:

|

|

6. Rapid spread of new/ harmful false information e.g. when:

|

|

7. Undermining public order and safety, or frontline/aid workers e.g. when:

|

|

8. Incident compounds or contributes to longer term challenges e.g. when:

|

Responding to information incidents

Incidents with a slower onset allow for more thorough preparation and planning. Others may hit suddenly, requiring an immediate response. The Framework can help you to design a collaborative response in either scenario.

Selecting joint or individual aims

First, the Framework asks users to commit to an aim - this can be a joint aim with shared responsibility between two or more organisations, or one where a single organisation is well-suited to carry it out alone. Organisations might prioritise aims differently, but communicating about intentions and using shared terminology can make a huge difference when collaborators are under time pressure or when lives and safety are at stake.

|

Aims |

|

Build audience resilience, e.g. run rapid information literacy education campaigns to particular or mass audiences |

|

Communicate and debunk effectively, e.g. adapt communications and debunk for different audiences, including translation, style of language, design, and dissemination channel |

|

Contextualise information and provide alternative trustworthy sources of information, e.g. Apply warnings, pop-ups and labels |

|

Create and use systems for evaluation and accountability which openly demonstrate proportionality and effectiveness, e.g. enable independent experts to scrutinise AI recommendations and report on problematic or dangerous patterns/issues emerging |

|

Disseminate accurate information appropriately to public and affected groups, e.g.promote alternative coverage from trustworthy media and fact checkers |

|

Plan and coordinate with others, e.g. coordinated messaging |

|

Pre-empt predictable misinformation, e.g. briefings to politicians and officials in the immediate aftermath of a crisis informing of major false claims circulating |

|

Preserve spaces where activists, opposition and journalists can work freely and open dialogue can take place, e.g. disseminate solidarity statements against governments and other entities which restrict freedom of speech and expression |

|

Restrict spread of harmful information, e.g. reduce circulation of harmful false content |

|

Share information and insight to gain a shared assessment of the situation, e.g. notify others when information moves from one platform to another/one region to another |

|

Strengthen policies and/or regulatory environment, e.g. strengthen moderation enforcement policies |

|

Support availability of reliable information from authoritative sources, e.g. reallocate staff in order to better provide information about issues of current public interest |

Identifying appropriate responses

Following on from aims, the Framework then proposes examples of responses that would meet different aims. These need to be adapted to the severity of the incident, and timing needs to be considered: some responses will have short term effects rather than long term ones, and vice versa. Different actors might also come up with alternative responses based on their own experience and judgement.

Example scenario

In this example there are information vacuums: official advice is changing quickly and there is uncertainty about the future. Three relevant aims are illustrated below with examples of how responses can be adapted to severity from Level 2 onward, when the incident starts to emerge.

|

Level 2 CrowdTangle is showing that there are several unconfirmed and false narratives appearing, mainly on one platform. There are a couple of accounts sharing the misinformation, but they have small followings. The misinformation itself would be harmful if lots of people acted upon it, but total views and engagement remain low, despite a few spikes. |

Aim 1: Contextualise information and provide alternative trustworthy sources of information

Aim 2. Pre-empt predictable misinformation

Aim 3. Plan and coordinate with others

|

|

Level 3 False narratives are spreading across more platforms in the absence of robust information about the situation, and views are increasing. As authorities backtrack on what they said before and an influential politician contradicts them, hashtags are emerging and influential accounts are sharing unconfirmed and false narratives. As more people view the content the risk of harm to minority groups is increasing. |

Aim 1: Contextualise information and provide alternative trustworthy sources of information

Aim 2. Pre-empt predictable misinformation

Aim 3. Plan and coordinate with others

|

|

Level 4 False narratives have taken hold across all major platforms and some media organisations are airing these, as there is no certain information from authorities to report. There are multiple hashtags and some coordinated amplification appears to be fanning the flames and successfully encouraging people to act in ways that are harmful to others. |

Aim 1: Contextualise information and provide alternative trustworthy sources of information

Aim 2. Pre-empt predictable misinformation

Aim 3. Plan and coordinate with others

|

|

Level 5 Misinformation is spreading across borders and is being linked to abuse of minority groups in neighbouring countries; there is evidence that coordinated amplification is contributing to this. Views and engagement continue to rise rapidly, and new false claims emerge and drown out attempts by authorities to put their version of events across. In affected countries, search queries and hashtags linked to the false information are dominant in trends. |

Aim 1: Contextualise information and provide alternative trustworthy sources of information

Aim 2. Pre-empt predictable misinformation

Aim 3. Plan and coordinate with others

|

Using the Framework

See: Using the Framework

How the Framework was created

See: How the Framework was created

How to get involved and give feedback

See: How to get involved and give feedback

[1] World Health Organisation, “Emergency Response Framework”, second edition, who.int, 2017; HM Government, “Emergency Response and Recovery non statutory guidance accompanying the Civil Contingencies Act 2004”, gov.uk, 2013

[2] Wardle, Claire, and Derakhshan, Hossein, “Information Disorder: Toward an interdisciplinary framework for research and policy making”, Council of Europe, 2017

[3] https://www.who.int/health-topics/infodemic

[4] Rahman, Grace, “Here’s where those 5G and coronavirus conspiracy theories came from”, Full Fact, April 2020

[5] https://fullfact.org/media/uploads/tpfc-q1q2-2019.pdf#page=32

[6] Funke, Daniel and Benkelman, Susan, “5 lessons from fact-checking the Notre Dame fire”, Poynter, 2019

[7] Abdelaziz, Rowaida and Robins-Early, Nick, “How A Conspiracy Theory About The Notre Dame Cathedral Led To A Mosque Shooting”, HuffPost, 2019

[8] Euractiv with AFP, “Pogroms attest of growing anti-Syrian sentiments in Turkey”, Euractiv, 2021 https://www.euractiv.com/section/global-europe/news/pogroms-attest-of-growing-anti-syrian-sentiments-in-turkey/

[9] Thanks to Teyit for providing extra information on this case study.