BBC Question Time, factchecked

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“One of the things that's been reported is that the EU wants, before they negotiate on a trade deal, us to pay £60 billion max, something like that, to the EU before talks start.”

David Dimbleby, 19 January 2017

Versions of this figure, in both pounds and euros, have been circulating for some time, but there’s no official line from the EU itself. We’ve been unable to verify the claim yet.

We spoke to the producers of BBC Question Time who said that Mr Dimbleby was referring to an article published in The Times saying that the Prime Minister has been told that the deal on exiting the EU would have to be agreed before any deal on a new trading relationship with the EU can be started. It said this could include paying the EU “a bill of up to £60 billion”

The Times told us that this figure refers to an estimate of what the UK might have to pay towards the EU up to 2020/21. This is the date that the current EU budget lasts until. It also includes other outstanding payments to the EU and contributions towards the pensions of EU officials. It worked out that could cost £60 billion or €70 billion.

We contacted the European Commission about the figure, but they told us they couldn’t comment.

Experts have told a committee of MPs that payments could include any outstanding contributions to the EU budget. They also said that, because of the way the EU’s spending works, some of this money may even be paid after that date, as far ahead as 2023 or even 2030. There may also be payments which have spilled over from previous years.

They said there are a number of ways that the UK’s pension contributions could be calculated so it's hard to come up with an exact figure. Altogether the experts said it could be anything between €20 and €60 billion.

Professor Iain Begg, writing for UK in a Changing Europe, said that it’s still an open question whether or not the UK will have to pay the full amount to the EU after the date of Brexit.

We’ve written before about the likelihood of the UK having to pay over £20 billion over the next two years while we negotiate our exit from the EU.

The cost of cutting corporation tax

In her recent speech on exiting the EU, Theresa May said that if the UK failed to strike a favourable new trade deal with Europe, then among other things:

“...we would have the freedom to set the competitive tax rates and embrace the policies that would attract the world’s best companies and biggest investors to Britain.”

In other words, if the UK fails to strike a favourable trade deal, it always has the option of reducing corporation tax and drawing multinational investment and tax revenue away from its European neighbours.

Emily Thornberry made a reference to this on last night’s Question Time:

“If we leave the European Union in the way Theresa May is saying that we might have to, she's going to cut corporation tax, I think it's 120 billion over five years.”

Emily Thornberry, BBC Question Time, 19 January 2017

These figures are estimates from the Labour party, and Ms Thornberry has quoted them incorrectly. The £120 billion includes estimated money lost to tax reductions that have already happened or are already planned, not just the ones the Prime Minister is suggesting in her speech.

The Labour Party has estimated the direct effect of cutting corporation tax to the same rate as Ireland would build up to a £63 billion loss in tax revenue over the next five years. Ireland has the lowest tax rates in the OECD, an organisation of rich countries.

In other words, Labour estimates that the direct costs of carrying out Theresa May’s suggestion are about half what Ms Thornberry suggested.

And these figures only account for the direct effect of cutting corporation tax. That is, they don’t account for the way that different tax rates might affect where companies choose to locate and invest.

For example, companies might choose to move their operations to the UK and pay lower rates, rather than locate elsewhere. They might also comply more readily with tax laws.

There’s no guarantee that either of these things would happen.

But because Labour’s estimates only account for the direct effect they shouldn’t be treated as complete estimates for the overall impact of cutting corporation tax on government finances, or assumed to be the only ones out there.

£60 billion lost tax receipts over the course of this parliament would still create a sizeable hole in the government’s annual income. It’s equivalent an average annual loss of between £12 billion and £13 billion a year, out of an average income of about £800 billion a year over the same time period.

Labour’s figures

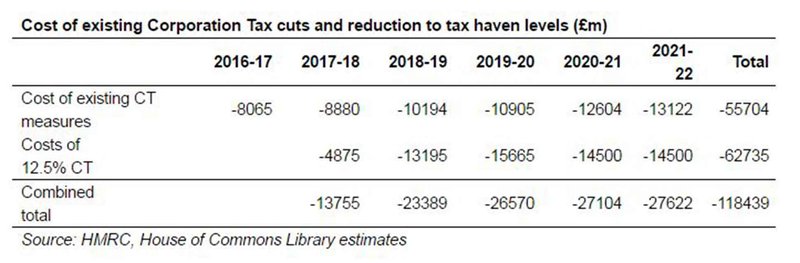

When Jeremy Corbyn made a similar claim in parliament this week, Labour supplied us with this table of estimates:

The first line estimates the tax lost each year because of cuts to corporation tax rates since 2010, running up to £56 billion between 2016-17 and 2021-22.

The second line estimates the extra losses that might come from cut corporation tax further and became a ‘tax haven’, as Labour puts it. If we had the same corporation tax rate as Ireland, Labour suggests the government would lose another £63 billion between 2017-18 and 2021-22.

Labour’s press release

A recent Labour press release also quoted these figures incorrectly. It said:

“Estimates from the House of Commons Library suggest that on top of existing corporate giveaways the cost of slashing corporate taxes to match tax havens like Ireland would be a shocking £120bn over the next five years.”

Labour Press, 17 January 2017

That claim doesn’t match the estimates supplied to us by the Labour party.

The table it sent us suggests that the direct costs of cutting corporation tax to match Ireland would be about £63 billion over the next five years, on top of existing ‘corporate giveaways’ worth about £56 billion.

Combined together, these would add up to an accumulated cost of nearly £120 billion, not accounting for the indirect effects of tax cuts.

“The amount of tax paid by the wealthiest in our society has risen and risen in the last few years”

Chris Grayling, 20 January 2017

That depends on two things: which taxes you’re looking at, and who you count as the ‘wealthiest’.

We’re also limited in what we can know by the data that’s available. For example, there’s a lot we can say about what the highest earners pay, but figures by wealth are harder to come by.

Here we give figures based on what the highest earners pay, but remember this isn’t the same as the ‘wealthiest’. We’ve asked Mr Grayling how he’d define the term.

The share of income tax contributed by the top 1% has generally been rising

You might see this kind of claim a lot—including during last week’s Question Time—referring to how much income tax the top 1% of earners are paying.

This year the top 1% will pay 27% of all the income tax the government takes in. That’s down slightly on last year, but higher than the share in previous years.

But this is only part of the picture. Income tax might be the government’s biggest single source of income, but three-quarters of the government’s revenue comes from elsewhere.

The share of total taxes contributed by the top 10% isn’t changing

That’s why it’s better to look at what top earners pay in all taxes: those on what people earn like income tax and national insurance, plus those on what people buy like VAT and tobacco duties.

The published figures only show what the top 10% of earners contribute, but it’s a start.

In 2014/15, an average household in the top 10% paid nearly £38,000 in taxes. As a group, they contributed about 27% of all taxes paid. A household in the bottom 10% would have paid just over £5,000.

The share paid by the top 10% is hardly changing. In the last six years it’s been about 27%.

Of course, we’d expect the richest to be contributing more to the total tax pot: they earn more and spend more, so there’s more to tax.

But what about what the richest pay out of their own budgets?

The top 10% are paying a similar share of their income in tax

The latest figures show the highest earning 10% paid about a third—34%—of their income in tax. To put that in money, in 2014/15 a typical top 10% household would have got £110,000 in income and benefits, and would have lost about £38,000 of it in taxes of various kinds.

Again, that share has hardly changed in recent years, varying from 33% to 35%.

That share is slightly more than what people on lower incomes pay. Only the bottom 10% buck the trend: they pay about 47% of their income in tax.