BBC Question Time: factchecked

This week Question Time was in Exeter. On the panel were minister for Brexit Suella Braverman MP, shadow treasury minister Clive Lewis MP, CEO of sportswear firm Head, Johan Eliasch, deputy editor of the New Statesman Helen Lewis, and journalist and broadcaster Janet Street-Porter. We factchecked claims on the UK's trade with the EU, whether Heathrow Airport is used primarily by people on expensive flights, the UK's carbon emissions targets, and funding for the armed forces.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

“Heathrow Airport is used primarily by people on expensive flights, most of the people watching this programme and most of the people in this audience do not go through Heathrow. They travel on budget airlines out of Luton, Stansted and so on. Heathrow is used by businessmen and women who get off one plane and get on another.”

Janet Street-Porter, 28 June 2018

More people flying from Heathrow are on connecting flights or business trips than at most other major UK airports. But the majority are leisure travellers and on terminating flights (as opposed to connecting ones).

The data referenced comes from a survey of passengers flying out of airports, conducted by the Civil Aviation Authority, the aviation regulator. It surveys a representative sample of departing passengers at most of the UK’s large airports.

In 2017 the survey found that 26% of passengers departing Heathrow were flying for business reasons, higher than other London airports included in the study (except London City airport at 50%).

It also found that 34% of departing passengers from Heathrow were on a connecting flight (i.e. they had flown into Heathrow and were now immediately flying out on another flight). Of the London airports, Gatwick had the next highest proportion of connecting flights at 8%.

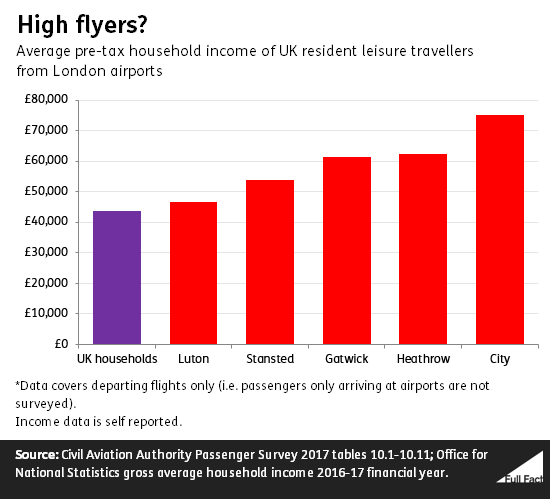

The survey asks respondents how much their flight cost, but that information isn’t published. What we do know is the average income (before tax) of passengers at each airport.

Again, according to the survey Heathrow’s passengers say they have higher average incomes than at other London airports, except City, though this includes all passengers, not just UK residents. As income is to some people sensitive personal information, it’s worth bearing in mind that not all people report their income in surveys.

Looking just at UK residents travelling for leisure reasons, City fliers (£75,000) have slightly higher average household incomes than Heathrow fliers (£62,000).

More generally, air travellers have higher incomes than the average. Survey data from 2014 found passengers with higher incomes were more likely to have flown in the previous 12 months.

The average household income of UK leisure passengers flying from London airports was higher than the UK household average of around £44,000.

"This week, the climate change committee has reported back that the Government is now way off target with its climate change commitments and carbon targets."

Clive Lewis MP, 28 June 2018

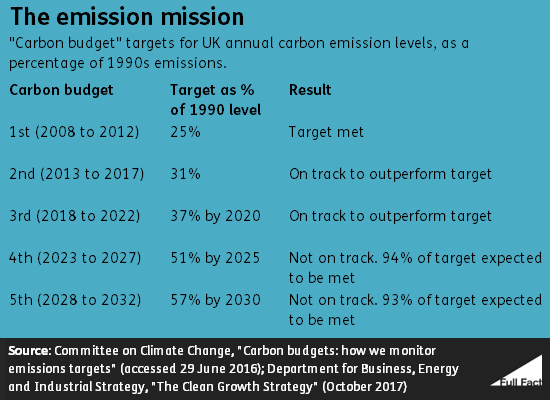

The UK has a target of reducing its carbon emissions to 80% below 1990 levels by 2050, as set out in the Climate Change Act 2008. To meet this target, the UK also sets “carbon budgets” on how much carbon it can emit in a five-year period.

Lord Deben, Chairman of the Committee on Climate Change this week said “the fact is that we’re off track to meet our own emissions targets in the 2020s and 2030s”, based on the carbon budgets for that period. The Committee on Climate Change is an independent body which advises the government on emissions targets, and was formed under the Climate Change Act 2008.

The UK sets five-yearly carbon budgets

“They restrict the amount of greenhouse gas the UK can legally emit in a five year period”, with the goal of reducing the UK’s carbon emissions to 80% below 1990 levels by 2050.

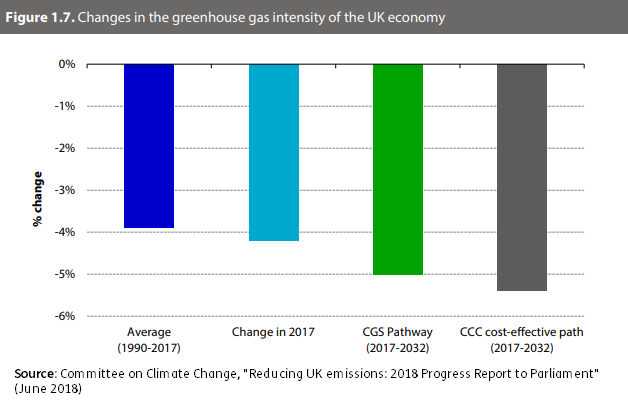

They point out that in its Clean Growth Strategy, “the Government stated that a 5% yearly reduction (in emissions) was required to 2032 to meet the fifth carbon budget. The reduction in 2017 was therefore not on track”—it was around 4% in reality.

They also point to three key reasons why the government is not on track to meet its carbon budgets in the 2020s and 2030s:

- They identify that two-thirds “of potential emissions reductions from existing policies are at risk of underdelivery.”

- A range of “ambitious proposals” the government made in its Clean Growth Strategy for dealing meeting emissions targets (such as phasing out sales of conventional cars and vans by 2040) are yet to be “turned into firm policies”.

- “There are cost-effective opportunities to further reduce emissions” where there is no government policy in place, and these aren’t being realised. They include creating “a route to market for the cheapest forms of low-carbon electricity generation (i.e. onshore wind and solar)”.

What has the government said?

In its Clean Growth Strategy from October 2017, the government recognised that it would probably not meet its targets for the two carbon budgets running between 2023 and 2032: “Our current estimated projection for the fourth and fifth carbon budgets suggests that we could deliver 94 per cent and 93 per cent of our required performance against 1990 levels”.

They point out that they are allowed some “flexibility” in meeting these budgets, under the terms of the Climate Change Act 2008. For instance, they can “borrow” carbon usage from a future budget (which is then itself “tightened”), with the Committee on Climate Change’s approval.

They also argued at the time that “ambitious policies and proposals set out in this Strategy, and the rapid progress and accelerating pace of changes in low carbon technologies so far, suggest that we may not need to use this option.” However, the Committee on Climate Change’s most recent assessment suggests that evidence for this progress is yet to be brought to light.

“It was a Labour government that left our defence budget in a parlous state with a £38 billion black hole."

Suella Braverman MP 28 June 2018

This is a claim with a long and difficult history, and has never been fully and publicly substantiated by the government.

We factchecked the same claim in 2011 and again in 2012 and 2014. At those times the Ministry of Defence (MoD) provided little supporting evidence to explain the figure, and the Commons Defence Committee said in 2011 it couldn’t verify the statement based on the limited information it was given from the government.

We got in touch again with the Ministry of Defence who directed us to the 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review, which is where the figure first surfaced. It wasn’t aware of any further updates to the figure since we last looked at the issue.

What we know now

The ‘black hole’ is a funding gap, here covering a 10 year period. It broadly refers to the difference between what the MoD thinks it will need to fund in future and its actual budget—assuming the budget only rises in line with inflation.

So to close a funding gap, the government has to either increase the budget beyond inflation year-on-year, or make savings.

It’s not a very precise figure either. Estimating your future costs is difficult. Defence budgets have to take into account things like changes in fuel price and exchange rates, which tend to be volatile. The pound dropped significantly against the US dollar following the EU referendum in 2016, for example, which couldn’t have been predicted back in 2010.

The government published a breakdown of the claimed £38 billion gap: £20.5 billion was down to equipment procurement and support and the rest on “other pressures” such as the costs of employing service personnel.

But these figures differed markedly from estimates produced by the National Audit Office (NAO) at the time, putting the funding gap at £6 billion over the decade.

So what’s happened to the ‘gap’ since then?

There’s no equivalent estimate for the size of the current gap overall—instead the National Audit Office has published a series of reports looking at funding pressures in different parts of the defence budget like equipment, estates and personnel.

At the start of 2018 it found—based on figures agreed with the Ministry of Defence—that the government’s 10-year plan for defence equipment wasn’t affordable. “At present the affordability gap ranges from a minimum of £4.9bn to £20.8bn if financial risks materialise and ambitious savings are not achieved.”

The MoD disputes the NAO’s interpretation of the gap, saying the higher end of the estimate is unrealistic and that it expects to make efficiency savings to help deal with it.

The NAO has also identified funding gaps in other parts of the defence budget: “Our past work has identified an £8.5 billion funding gap for managing the Department’s estate. Also, the Department faces challenges in managing its staff budget.”

"We are the second-largest market in Europe so of course people are not going stop selling here... We have a £100 billion trade deficit with Europe."

Johan Eliasch, 28 June 2018

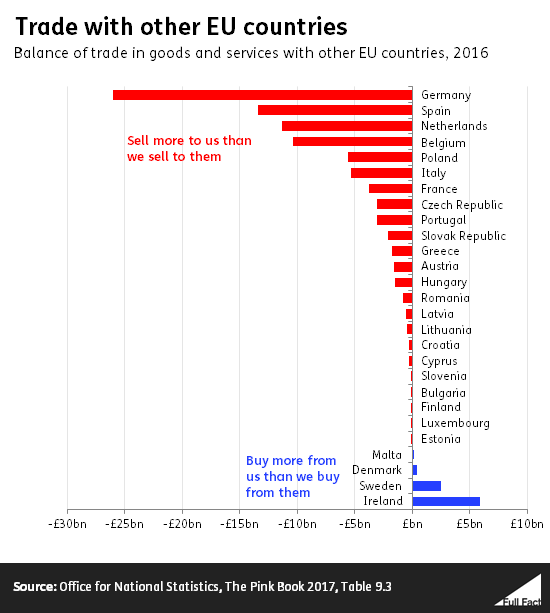

We import more from the EU than we export to it. This is known as a “trade deficit”, as we’re buying more than we are selling.

In 2017, the UK was the third most populated country in the EU, after Germany and France. As of 2016, it was the EU’s second largest single export market for goods.

Excluding trade between EU countries, the UK came second only to the US in goods exports from the EU.

The rest of the EU countries altogether sold about £67 billion more in goods and services to the UK than we sold to them in 2017, according to UK data. In 2016, this was closer to £75 billion.

Our exports to the EU were worth about £274 billion in 2017, while the UK imported £341 billion’s worth.

Between the UK and individual countries within the EU, our biggest trade deficit is with Germany, which sold us £26 billion more goods and services to us than we sold to it in 2016.

We did not have trade deficits with Malta, Denmark, Sweden or Ireland in 2016, as we sold more to them than they sold to us. We sold almost £6 billion more goods and services to Ireland than we bought from it in 2016.

You can read more about trade with the EU in our explainer here.

How does this compare to the UK’s other trading partners?

In 2016 the UK bought more than it sold to Asia by around £20 billion (so another trade deficit there). In 2017, China sold more to us than we sold to them by about £23 billion.

It’s the opposite case for trade with the US. In 2017 we sold over £40 billion more to the US than we bought from them.

We sold more to countries in Africa than we bought by £3 billion in 2016.