In recent years, the number of stop and searches has decreased dramatically, after reviews of the policy called for a more “fair and proportionate use of the power”.

When stop and search was used more widely, including from spring 2008-2011 when the Metropolitan Police initiated its Operation BLUNT 2 strategy, the number of arrests was higher, but the arrest rate was lower. But arrests aren’t the only thing which police bodies define as a ‘successful outcome’ for a stop and search.

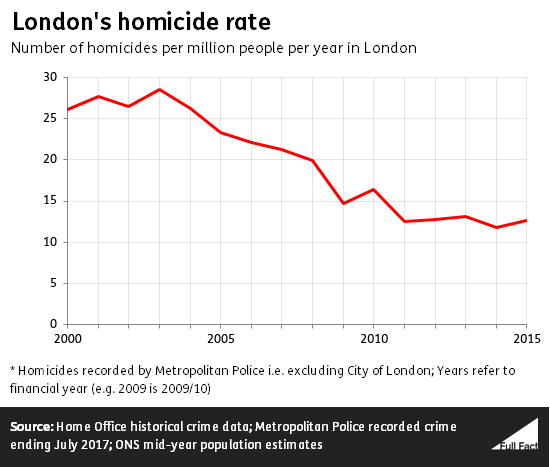

Under Mr Johnson’s time as Mayor of London, the homicide rate halved, before rising again towards the end of his tenure. The number of homicides only dipped below 100 in 2014; not for multiple years.

We’ve asked Mr Johnson’s office for the source of these claims, but haven’t received a reply yet.

Searches and arrests down; arrest rates up

From April 2009 to March 2010 there were 1.4 million stop and searches in England and Wales compared to 300,000 in 2016/17. The fall in London was similar from 670,000 to 138,000 over the same period.

It’s correct that when stop and search was used more widely it led to a higher total number of arrests. But back in 2010, when stop and search was at its peak, the arrest rate was also significantly lower.

Even then, it’s difficult from these figures to judge how effective stop and searches are as it assumes that they’re only successful when they lead to arrests.

Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services notes that an arrest isn't necessarily a success, nor is a failure to uncover any wrongdoing necessarily a failure.

Offenders could, for instance, be arrested even if they're found to be empty of stolen or prohibited goods because they might react violently to officers or be wanted for another offence. On the flipside, failing to uncover wrongdoing could be regarded as a success if, without the stop and search powers in place, the person under suspicion would otherwise have been arrested unnecessarily.

Also, arrests aren’t the only “positive outcome” that can result from a stop and search. Metropolitan Police data shows that in 2017 while 19% of stop and searches led to arrest, another 13% of stop and searches led to other “positive outcomes” including warnings and penalties. We don’t have similar data at a national level to see how positive outcomes have changed since the reduction in stop and search.

It’s also possible to look at whether stop and search acts as a deterrent to future crimes. A 2017 report found that areas in London with higher rates of stop and search had “very slightly lower than expected rates of crime in the following week or month” by analysing data from 2001-2014. The authors found the deterrent effect of increased stop and search on violent crime specifically was, at most, “negligible”.

Mr Johnson specifically referred to the success of Operation BLUNT 2, a Metropolitan Police initiative from 2009-2011 that tried to reduce knife crime by increasing stop and searches for weapons. A Home Office evaluation in 2016 found "that the greater use of weapons searches was not effective at the borough level for reducing crime.”

The murder rate

It’s correct that the homicide rate recorded by the Met Police halved between 2007 and 2014, during Mr Johnson’s time as mayor, before increasing slightly towards the end of his tenure.

Homicide figures are often used to describe the number of murders or the murder rate, but these figures include manslaughter and infanticide charges as well as murders. The available figures do not record murder, manslaughter and infanticide separately. We’ve asked Mr Johnson’s office for the source of these claims, but haven’t received a reply yet. We’ve assumed he was using the term “murder” and “homicide” interchangeably.

In the year before Mr Johnson became mayor (2007/08), there were 163 recorded homicides, or roughly 21 per million, using population estimates for the time. In 2014 the rate had reduced to 11 per million, down by about half, though this had ticked up slightly to 13 per million in the year from April 2015 to March 2016, Mr Johnson’s last year in office.

Homicides are relatively rare, so these figures can vary a lot from year-to-year. Taking a broader view, the rate during

Mr Johnson’s time as mayor averaged 14 per million people living in London. The rate during Mr Livingstone’s

eight years as mayor averaged 25 per million.

We haven’t found evidence that there were fewer than 100 murders for several years. Data from the Home Office shows there was no financial year in which the number of homicides fell below 100. As mentioned above, the number of murders specifically (not including manslaughter and infanticide) may have fallen below 100.

The Metropolitan Police also publishes homicide data on a monthly basis, which shows that in 2014 there were 92 homicides, the only year during Mr Johnson’s tenure when the total dipped below 100.