Economy introductions: the size of government debt

The government owes £1.8 trillion, up from about £1 trillion in 2009/10.

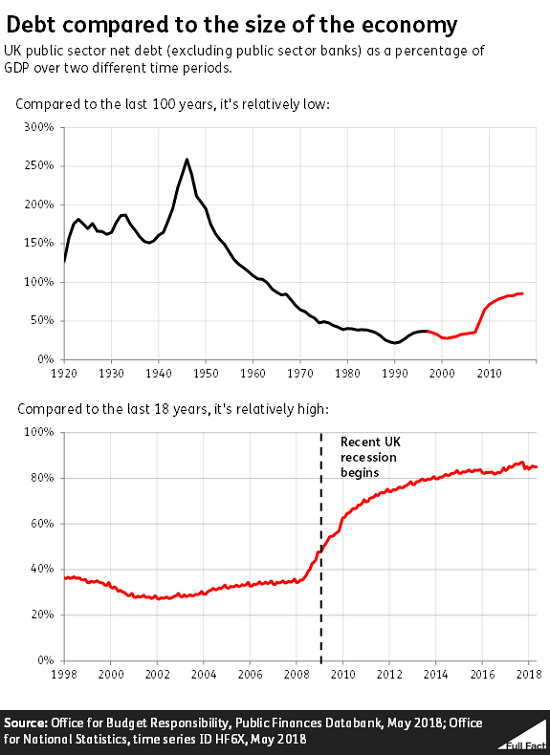

It's common to compare government debt to the size of the UK's economy (GDP). The Office for National Statistics says that’s worth about 85% of GDP, up from 67% in May 2010. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) expects debt to start falling as a percentage of GDP from this financial year onwards.

We're quoting the main official measure of government debt: public sector net debt excluding banks. This is what the government owes to the private sector. It doesn’t include money owed between different branches of the state—in other words, it doesn’t count what the government owes itself—or the debts of banks owned by the government.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Debt versus deficit

It’s not to be confused with the government deficit.

The deficit is the difference between the government’s income and government spending. It’s the amount the government has to borrow each year.

Debt is the total amount of money owed at one time, most of which is made up of gilts auctioned by the government. The owner of a gilt gets paid interest until the government pays the debt back.

Borrowing money to cover the deficit adds to the total stock of national debt.

When does it have to be paid back?

In one sense, it doesn’t. Government gilts are issued with a date when they have to be paid back, but at that point the government can just issue new gilts to pay for the old ones—as long as investors are happy to buy them.

What costs money is the interest payments the government has to make in the meantime. About 5% of the government budget goes towards paying interest on the national debt.

Who owns the debt?

Most UK government gilts are owned by British institutions, and some by UK households. They get the interest payments.

UK insurance companies and pension funds own almost a third: about 30%.

The Bank of England owns about a quarter.

Other UK financial institutions like banks own 17%, just over a sixth.

Another quarter of the government’s debts, about 27%, are owed to foreign institutions. That’s called the UK’s external debt, and the interest payments go outside the UK.

Debt-to-GDP ratios

It’s common to compare the value of a government’s debt with what’s called annual gross domestic product, or GDP. That’s the total value of goods and services made in the UK each year.

The government’s net debt was worth about 85% of GDP at the end of May 2018.

Looking back at the last century, 85% is a relatively low ratio, especially compared to the post-war periods.

But compared to the last two decades, it’s relatively high. The size of government debt increased greatly in proportion to GDP around the time of the last recession.

Size isn’t everything

Comparing debt to GDP has two big advantages over looking at the size of the debt alone. First, it gives a sense of how debt compares between different sized countries. Second, it gives a sense of how the debt has changes over time as the UK’s economic output has increased.

There’s a view that the debt-to-GDP ratio indicates whether the country is likely to run into economic difficulties. The bigger a country’s GDP, the easier it is for the country to support high government debt.

But looking at the relative size of government debt won’t give you a full picture of its significance.

As an example, the United States has a relatively high debt-to-GDP ratio, compared to other countries. But no-one thinks that the United States government is about to default on its loans—they’re considered one of the safest investments in the world.

As long as people believe that a government will pay the interest on its debts, that it won’t suddenly default on them, and that they’ll be able to sell their ownership of the debt easily when they need to, investors will carry on lending that government money.

While the size of UK debt has continued to increase in the past few years, other factors have meant that it’s actually become cheaper for the UK government to borrow money. So size isn’t everything.

There’s a debate about what constitutes a sustainable level of debt for a developed country like the UK, and the economic significance of changes in the debt-to-GDP ratio.