A very old problem: productivity in Britain

"Now a lot has been written about the productivity puzzle. Why, for so many years, have British workers been less productive than their German or American counterparts? Why has productivity been so damaged by the Great Recession?"—Chancellor George Osborne, 20/05/2015

Britain has a productivity problem. Although on average we work longer hours than Germany and France, we actually produce less per worker than they do.

While this issue took a back seat during the election campaign, the Chancellor has stated that addressing the causes of low productivity is high on his agenda for this parliament.

Measuring productivity

The ONS measure productivity by looking at how much is produced for each hour worked, dividing GDP by the total number of hours worked.

Join 73,000 newsletter subscribers who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

This is a measure of how productive British workers are, rather than a measure of how efficiently we produce output. Using more equipment makes workers more productive, but it's not an improvement in the overall efficiency of production; we're using more to produce more, not producing more using our original setup.

Are we less productive than the Germans?

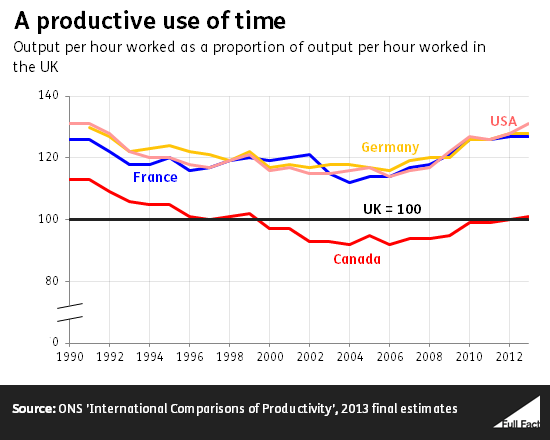

In 2013, an hour's work in Germany produced 28% more output than an hour's work in the UK. In the United States, an hour's work produced 31% more output. More Gaul-ingly, output per hour worked in France was 27% higher than it was here.

Even the longstanding comfort of not being Canada has been snatched away from us; after a bit more than a decade of higher British productivity, the Canadians overtook us in 2012.

This isn't a new problem; things were much the same in 1991, suggesting that there are some fairly entrenched problems underlying this.

Why are we talking about this now?

In the run-up to the election, British productivity was not high on the agenda for the Conservatives. Apart from government IT projects, the sole appearance of the word productivity in the Conservative manifesto was the sentence

"Productivity remains too low."—Conservative manifesto, page 49

While some policies were clearly targeting this problem—for example, increasing investment in infrastructure—improving productivity was not treated as a core 'message'.

Labour were a little keener. Their 85 page manifesto featured about three pages on this subject.

For whatever reason, addressing long-standing problems in an election campaign apparently wasn't very appealing. Employment, public finances and wages sat at the heart of the economic arguments put forward by both parties.

What causes low productivity

So why is British labour so unproductive? George Osborne provided a pretty good summary in his speech to the Confederation of British Industry:

"Frankly, nobody knows the whole answer"—George Osborne, 20/05/2015

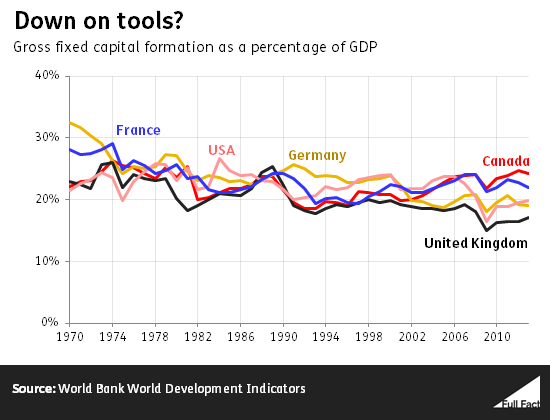

What we do have are lots of little parts of the answer. We invest less in equipment and infrastructure than comparable countries do, and have done for some time. We also spend less on R&D.

Part of the problem of low investment is comparatively poor infrastructure. Congested roads and crowded railways make commuting unpleasant, and moving goods around the country more expensive.

Our workforce is not as skilled as it might be. A particular weakness is the development of intermediate skills, which are essential for the 'skilled trades' like carpentry and plumbing, and the proportion of adults who lack basic literacy and numeracy skills remains a problem. This lack of skills is one which extends to managerial competence.

There is no 'silver bullet' here, and no quick fix. Just reading the list above makes it clear that closing the productivity gap involves correcting a number of different problems even when talking in the most general terms. If we were to look closer at these issues we would find even more problems underlying them.

Take, for example, low investment. Is excessive 'short-termism' in financial markets the main problem? How do we go about fixing this? Or take the skill shortage. How do we actually improve the quality of schools and apprenticeships?

None of these are new problems. Each of them had already been apparent for some time over a decade ago. This suggests that while it's easy to talk about fixing them, actually doing so is a formidable challenge.