Academies and maintained schools: what do we know?

- Academies receive their funding directly from the government, rather than through local authorities like other state funded schools.

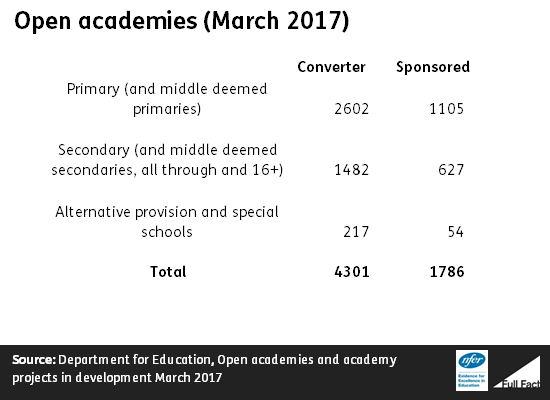

- There are two types: converter academies (those deemed to be performing well that have converted to academy status) and sponsored academies (mostly underperforming schools changing to academy status and run by sponsors).

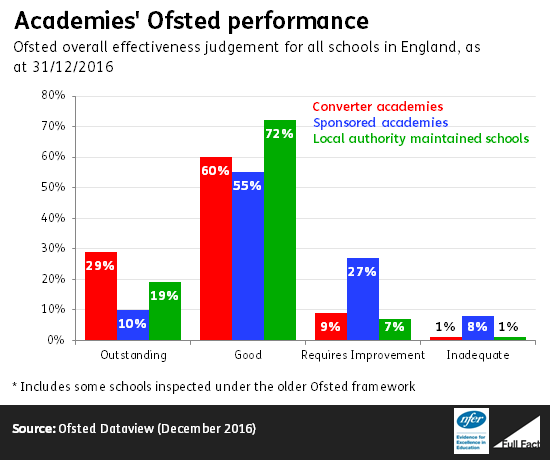

- Comparing the most recent Ofsted grade of each type of school, converter academies are the most likely to be good and outstanding while sponsored academies are more likely than maintained schools to be graded requires improvement or inadequate. But this is to be expected as converters were high performing, and sponsored low performing, to begin with.

- Evidence on the performance of academies compared to local authority schools is mixed, but on the whole suggests there is no substantial difference in performance.

State-funded schools (including primary, secondary and special schools for pupils with special educational needs) fall into two main groups:

- Maintained schools—where funding and oversight is through the local authority. These are the majority of schools and are mostly either community schools (where the local authority employs the school’s staff and is responsible for admissions) or foundation schools, where the school employs the staff and has responsibility for admissions.

- Academies—where funding and oversight is from the Department for Education (DfE) via the Education and Skills Funding Agency. They are run by an academy trust which employs the staff.

Grammar schools, are state-funded selective secondary schools. Most of these (140 out of 163) are now academies.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Academy freedoms

Academies are run by academy trusts and don’t have to follow the national curriculum and tend to have greater freedom to set their own term times and admissions (although this is a complex area).

They still have to follow the same rules on special educational needs and exclusions as other state schools, and are required to provide a curriculum that is “balanced and broadly based, and includes English, mathematics and science”. In terms of admissions, they also still have to follow the same rules as other state schools, but can set their own arrangements rather than these being determined by the local authority as is the case for many non-academies.

Evidence on the extent to which academies are using these new freedoms is mixed. A 2014 survey of academies by DfE found that 87% say they are now buying in services previously provided by the Local Authority from elsewhere, 55% have changed their curriculum, 8% have changed the length of their school day and 4% have changed their school terms. Whilst various other changes were also reported, it is not clear to what extent these are a direct result of academy conversion rather than changes that would have taken place regardless.

A similar survey by think tank Reform and education body SSAT found slightly different percentages, but concluded that in terms of providing “something new and different to the education that went before […] academies remain an unfinished revolution”.

Studio schools, university technical colleges and free schools are all types of academies.

Academies fall into two main categories:

- Sponsored academies—these have sponsors such as businesses, universities, other schools, faith groups or voluntary groups, who have majority control of the academy trust. Most, but not all, sponsored academies were previously underperforming schools that became academies in order to improve their performance.

- Converter academies—these don’t have sponsors, and are schools previously assessed as ‘performing well’ that have ‘converted’ to academy status.

There are around 6,000 academies open (excluding a further 400 free schools, studio schools and University Technical Colleges). About 4,300 are converter academies. A further 1,200 are in development.

Two-thirds are run by Multi-Academy Trusts

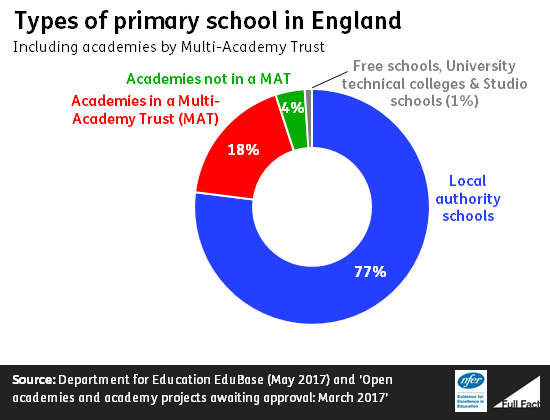

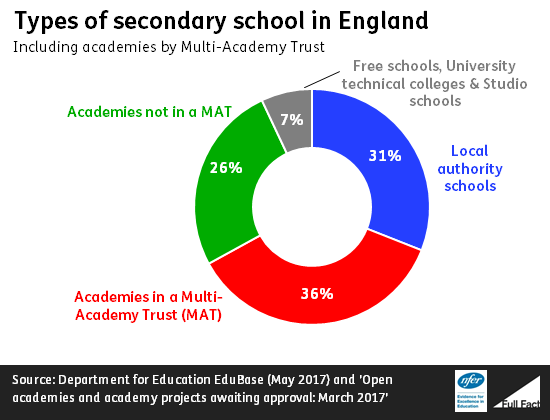

Roughly two-thirds (65%) of academies work together with others in academy chains governed by a Multi-Academy Trust, according to data from the Department for Education. That’s counting converter and sponsor led academies at primary, secondary and middle school level.

The number of MATs has rapidly increased since 2011 – from 391 in March 2011 to 1,121 in November 2016.

In 2015, the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee criticised the government for allowing academy chains to grow in size without independent assessments of their capacity and capability to do so. The National Schools Commissioner is seeking to address this by a programme of pilot ‘MAT growth checks’.

Ofsted Chief Inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw raised concerns with the government in early March 2016 regarding the performance of seven multi-academy trusts. He said that “much more needs to be done to reduce the variation in standards between the best and worst academy trusts”. The government is reported to have disputed this, saying these trusts represent a partial picture.

The government has now started to publish performance tables for MATs, which look at trusts with three or more mainstream academies.

The government has been criticised for a lack of accountability for academies

Academies, including free schools, are directly accountable to the Secretary of State for Education, while all other state funded schools are accountable to local authorities. Both are inspected by Ofsted. Ultimately, DfE is accountable for the overall performance of the school system in England.

The House of Commons Public Accounts Committee has said “The Department presides over a complex and confused system of external oversight”, “allowing schools to fall through gaps in the system”.

Regional Schools Commissioners (RSCs) were established as an extra layer of oversight in September 2014 with the responsibility for deciding which applications for academies would be taken forward, monitoring academy performance and also for taking action when an academy is underperforming. They are also meant to champion academy freedoms, alongside Headteacher Boards in each region which work with the RSCs to support struggling academies.

Their role has been expanded since then to include tackling underperformance in local authority schools. They are also responsible for deciding what action should be taken about academies and LA maintained schools that are identified by the government as “coasting”.

There are currently eight RSCs, each of whom face a very different task in terms of the number of existing academies and underperforming local authority schools in their region. Some regions, such as Lancashire and West Yorkshire, also don’t have enough academy sponsors to support schools identified as underperforming. We don’t have much evidence to see how well they’re working yet, although the Education Select Committee have made a number of recommendations for how the role could be clarified and improved.

The two main ways used to assess the success of academies relative to other schools are looking at Ofsted inspections, and examination results.

Comparing the performance of academies and maintained schools is difficult

One way to compare the performance of converter academies with other maintained schools is to compare those which started out with the same Ofsted rating.

Analysis by the Department for Education on this basis found no significant difference in the proportion of secondary converter and maintained schools keeping their outstanding status (35% vs 33%). Secondary converter academies previously graded good were more likely to improve (16% vs 10%) and more likely to retain (56% vs 49%) their Ofsted grade than previously good maintained schools.

But there may be other underlying differences between the schools that became academies and schools with the same Ofsted rating that did not become academies, which are likely to have influenced both whether the school became an academy and subsequent Ofsted grades.

The other—less informative— comparison is to look at the most recent Ofsted grade of each type of school. On this basis converter academies are the most likely to be good or outstanding, and the least likely to be graded as requires improvement or inadequate.

However, this is to be expected as schools are more likely to convert to academies if they’re performing well according to their exam results or Ofsted grade so it’s not surprising that these schools continue to be more likely to be judged Outstanding compared to maintained schools. There’s also the question over whether schools that haven’t yet been inspected under the new Ofsted framework should be included in the comparison.

Conversely, sponsored academies are more likely than maintained schools to be graded requires improvement or inadequate. Again, this is not necessarily surprising: transition to sponsored academy status has become the automatic recommendation following school underperformance.

We also have to be careful with comparing Ofsted data because the frequency of inspection differs according to what the school’s previous grade was: inadequate schools have another inspection within the next two years, whereas good and outstanding schools are inspected within the next five years (but may be sooner if concerns are brought to the attention of Ofsted). A school’s existing grade may not reflect the school’s current position if the most recent inspection was many years ago.

Analysis of GCSE results suggests academies generally do not perform better, but we don’t know as much about primary performance

Some have suggested it is too early to tell whether maintained schools that turned into academies since 2010 have improved compared to other maintained schools, and most of the research so far has considered secondary schools only: little work has been done looking at primary schools.

Looking just at the latest GCSE results, converter academies appear to be the highest performing: in 2015 63% of pupils in converter academies achieved 5 A*-C GCSE grades including English and Maths, compared to 55% in maintained schools.

Sponsored academies appear to be the lowest performing, with 45% of pupils having achieved 5 A*-C GCSE grades including English and Mathematics.

But, again, the differences mostly reflect the fact that converter academies were relatively high-performing before they became academies and sponsored academies relatively low-performing before they became academies.

In order to properly understand how academies have performed we need to compare them to similar schools still in the maintained sector.

One analysis by NFER comparing the performance of 7 to 11 year olds in primary academy schools in 2015 to their peers in non-academies found being in an academy made little difference to their exam results in the short term.

For secondary schools, the evidence is mixed. One such analysis found generally little difference in GCSE performance between both types of academy and similar local authority schools for academies that had been open for two to four years.

That conflicts with an earlier version of that research which found sponsored academies performed better than similar non-academy schools on some measures of attainment at GCSE. The official headline measures of attainment at GCSE level changed between the two pieces of research, which might explain why the findings were different. The more recent analysis draws upon the current headline measure.

None of this research tells us about the long-term effects on performance of becoming an academy.

Research by academics at LSE looking over a longer time frame found performance in sponsored academies increased more quickly than in similar schools in the mainstream sector. That’s comparing those academies to schools that were similar to them when they became an academy. The improvement was greatest in schools that had been academies for the longest, implying that the effect of academy status has a gradual impact on improving performance.

However, the 130 schools they looked at became academies between 2002 and 2009, under the Labour government, which represent just 6% of the much larger number of secondary academies we have now.

Ofsted commented recently that:

“inspection evidence, research and analysis continues to find that, while becoming an academy can be beneficial for some schools, there is not a clear or substantial difference between the performance of academies and schools maintained by local authorities.”

Further reading:

- This House of Commons Library note covers Frequently Asked Questions and the issues regarding Academies and free schools

- This House of Commons Library note covers Converter academies statistics: it shows the pattern of conversion over time, by school type and by area.

- Detailed explanations of school categories are available from the Department for Education and the New Schools Network.

This briefing was originally written by Geoff Gee, Jack Worth and David Sims of the National Foundation for Educational Research in collaboration with Full Fact in 2015. It has been updated by Geoff Gee and Karen Wespieser in 2017.

Image credit: Crown Copyright