How should we discuss risk vs benefit in the context of vaccination?

Guest authors

Professor Dame Sarah Gilbert is the Saïd Professorship of Vaccinology, based at the Pandemic Sciences Institute, University of Oxford. She was the Oxford Project Leader for ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, known as the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine against COVID 19.Sean Elias is Public Engagement with Research Lead for VaxHub, based at Oxford’s Pandemic Sciences Institute and has over a decade of experience working on vaccines and clinical trials. Through collaborations with schools, science festivals and science museums, he works on novel ways to take the science of vaccines, from the laboratory to public settings.

From a scientific perspective, there is little doubt that vaccines are one of humanity's most effective public health interventions, saving up to an estimated 3.5 to 5 million lives a year globally, according the the World Health Organisation.

Vaccines work by reducing both individual risk, through personal immunity, and societal risk, through herd immunity. When a vaccination campaign is successful, we can eliminate an infectious disease from a given area, country or region. This is one of the great triumphs of modern medicine, but there is a downside to such success. Without visual reminders of the risk of disease, populations may become complacent regarding vaccination. Risk associated with a given vaccine, if perceived to be greater than the risk of infection, may lead to vaccine refusal. For scientists, health care workers and policy makers, the challenge is how to convey relative or acceptable risk accurately and without bias.

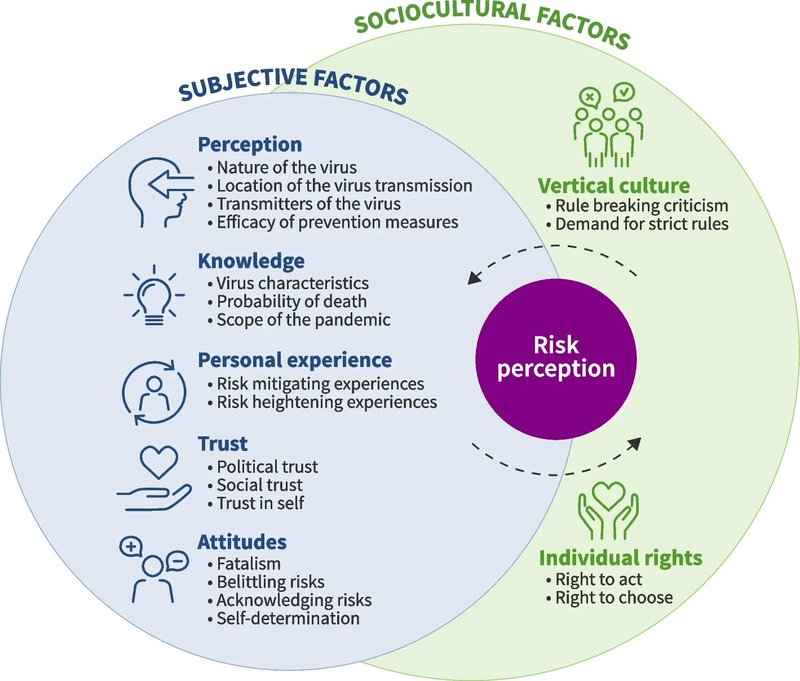

An individual’s perception of risk varies according to numerous factors. For familiar, everyday activities (e.g. driving a car), risk may be well understood and accepted, even when statistically higher compared to alternatives. But for situations where individuals have no prior experience or technical expertise (e.g. an outbreak of a new virus) people may be susceptible to over or under estimating risk.

One way to get that balance right is to do a risk-benefit analysis. For vaccines, this would typically be: what is the risk from the vaccine versus the risk from contracting a given disease? For highly fatal infectious diseases - for instance rabies with near 100% fatality - benefits of vaccination almost always outweigh the risks if you live in a country where the disease is endemic. However, if you live in a low-income country without freely available vaccines, a rabies vaccine might cost a month’s wages. Is the risk of not affording food worth the risk of a disease you might not get?

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

Such complex decisions require multiple considerations and are best backed by an evidence-based approach. However, throw in issues like access to reliable information, social and cultural pressures and mis and dis-information, and you have no clear route to an informed decision. To help people navigate this complexity, we can initially focus on what we know and can control.

Risks associated with vaccination can be grouped into known and unknown risks. Known risks include vaccine side effects and allergens. The most common side effects of vaccination are familiar, expected and easily explained. Fever, redness and localised pain at the injection site are essentially our immune system reacting to vaccination as it would to a real infection. Potential allergens that could be present in trace amounts in certain vaccine types—and that could pose personal risk to individuals—must be declared for safety purposes, just as they are with food products (such as ovalbumin in egg white). Websites such as the Vaccine Knowledge Project aim to increase transparency around vaccines, listing ingredients and offering advice on available alternatives for those with allergies or concerns.

The role of clinical trials is to assess both known and unknown side effects of vaccination and note whether their frequency and severity are acceptable in terms of safety, alongside vaccine effectiveness. However even clinical trials have limitations. A clinical trial may assess 250,000 people before a vaccine is licensed but if an immediate rare side effect only occurs in 1 in 1 million people it may not occur during the trial. Similarly, clinical trials typically only follow up participants for 6 months to 1 year, so potential long-term side effects could be missed. Such unknowns are most commonly cited by those concerned about new vaccines.

By contrast, vaccines that have been publicly used for extended periods are typically deemed lower risk by the public. During nationwide vaccination campaigns, millions of individuals are vaccinated increasing the likelihood of identifying rare side effects outside of the clinical trial setting. In the UK, both medical practitioners and the public can report potential vaccine side effects at any time to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) through the Yellow Card Scheme. The purpose of such schemes is to identify safety signatures that may not be picked up during clinical trials and if necessary pause use of a licensed medical product until it has been further investigated. In this context, when it comes to driving public perceptions of risk, no news is good news.

Whilst statistics can support a logical approach to calculating and presenting risk they have their limitations. Statistics can be misinterpreted or misrepresented if cause versus correlation is misunderstood. So, should we consider a more holistic view to convey risk to the public? One approach is to use story telling and the collective memory of those who have experienced infectious disease first hand or lived through riskier times. Survivor stories can evoke an emotional response and add relatability. Such factors can be incredibly important when engaging individuals who rely more on faith over facts for decision making.

In the modern world people are often more reactive than proactive and this can be seen in how people access information. For many, social media is their primary source and it’s a place where information travels and changes fast, making mis- and dis-information powerful and challenging to counter. Static websites are less useful for rebutting rapidly changing information, increasing the importance and need for sources of fast and direct fact checking. Crucially, organisations such as Full Fact work with experts, including scientists, doctors and statisticians, to provide counter-arguments in real time. Their aim is to strike a balance between the purely fact-based approach and the holistic story-based approach, in order to put risk in a context that can be understood by all.

The views expressed in this article are those of the guest authors.