Are fewer ethnic minority children being adopted?

"Ban on mixed-race adoption to be lifted under new proposals that could release thousands of children from care."

Daily Mail, 6 February 2013

Yesterday saw the publication of the Children and Families Bill, which now begins its long journey through Parliament. The Department for Education (DfE), spearheading the legislation, outlines on its website the key provisions of the Bill, including reform to adoption, the family justice system and the system for Special Educational Needs (SEN).

In keeping with its past reporting on the issue, the Daily Mail took particular interest the the Bill's promise to lift the "ban on mixed-race adoption" in England.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

So what is all this about?

When considering whether a child should be adopted, adoption agencies have to abide by the Adoption and Children Act 2002. The Act requires that the paramount consideration when a child is placed for adoption is its welfare throughout his or her life and, among other things, to have regard to further factors such as the child's own ascertainable wishes.

The key 'regard' here is that:

"In placing the child for adoption, the adoption agency must give due consideration to the child's religious persuasion, racial origin and cultural and linguistic background."

So this obviously isn't a "ban" as the Mail is terming it. There is, however, an acknowledged problem in practice. The Government and others are concerned that too many local authorities in England are putting too much weight on matching a child's ethnicity with prospective parents and hence causing delays in adopting black and Asian children.

The Government's action plan for adoption sets this out clearly:

"The delay faced by black children during this process needs particular attention. They take around a year longer to be adopted after entering care than white and Asian children. One reason for this is that in some parts of the system, the belief persists that ensuring a perfect or near perfect match based on the child's ethnicity is necessarily in the child's best interests, and automatically outweighs other considerations, such as the need to find long-term stability for the child quickly."

As a result, the Queen's Speech in 2012 set out:

"Stopping local authorities delaying an adoption to find the perfect match if there are suitable adopters available. The ethnicity of a child and prospective adopters will come second, in most cases, to the speed of placing a child in a permanent home."

And hence the legislation to this effect published yesterday.

The House of Commons Library provides a useful background note on inter-racial adoption with more detail.

What do the numbers say?

The Department for Education's regular statistical release on children 'looked after' and adopted in England is the place to go for most general figures in this field. They confirm many of the figures quoted in the media, so it's worth summarising what we know today:

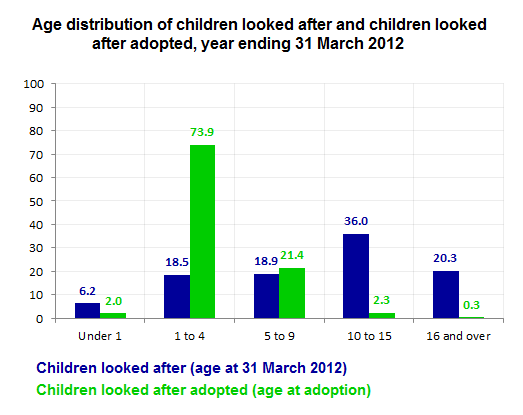

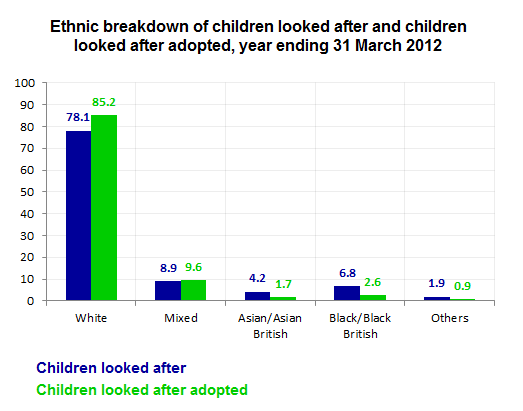

67,050 children (to the nearest 10) were "looked after" as at 31 March 2012 - most of these are in foster care provided by the local council, others are in children's homes, hostels and secure units. 55% are male, the majority are over 10 years old and around four fifths have a White ethnic origin.

The figures on adoption are somewhat bleak. 3,450 children (again rounded to the nearest 10) were adopted between April 2011 and March 2012. In keeping with previous years, roughly the same number of girls are adopted as boys, but the age difference is quite pronounced: three quarters of all children adopted were under 4 years old or younger. Meanwhile, 85% of adoptees were white.

Comparing the demographics of children in care with those of children who were adopted paints an indicative picture (breakdowns aren't avaiable for children placed for adoption) although it's important to bear in mind these don't allow us to draw too many conclusions about adopters' choice or adoption agency's placement criteria:

Another point is that the average adopton 'process' (which Full Fact has researched before) takes two and-a-half a years on average between entering care and adoption, and under one year between matching the child with adopters and adoption. So the ages at adoption aren't necessarily the same as the age at which the child is matched with prospective parents.

The same breakdown can be provided for ethnicity:

In line with what is often referred to in the media, there's a noticeable bias towards adopting younger rather than older children, and some against children of Asian and black ethnic origin. Whether the Government's new Bill will effectively tackle some of this bias remains to be seen.