Does a candidate need more than 50 per cent of the vote to win under AV?

The YES campaign says that a big advantage of the AV system is that MPs have to gain the support of more than half of voters in their constituency.

Jonathan Bartley of 'Yes to Fairer Votes' on Newsnight: "...you don't just have 30 per cent of people in a constituency electing an MP, you have 50 per cent... They will have to get 50 per cent of us to like them."

The Guardian, 30th of March, 2011: "...because, unlike the current system, it requires an elected MP to have the support of a majority of the votes cast."

However, 'No to AV' disagrees with this:

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

'No to AV': "The AV system being offered in May makes the ordering of preferences optional. Most voters would not work their way through ballot papers, exhausting every preference. Therefore a large number of MPs would win with less than 50% of the vote. Research has shown that 'more than 4 out of every 10 MPs would still be elected with the endorsement of less than 50% of the voters."

Facts

Under the proposed system of AV a candidate has to get more than half of the votes in a counting round to win — but after the first round, that is not necessarily a majority of votes.

Unlike the Australian model, the system of AV proposed for this country does not require the voter to express a preference for every candidate on the ballot paper.

If a voter chooses only to put a '1' by their favourite candidate, then their vote cannot be redistributed in the second and subsequent rounds because they did not express a second preference.

The more rounds of counting required to elect a winning candidate, the greater the chance that votes will cease to be counted as they had not expressed a preference for any of the candidates remaining in the election. The number of votes required to win the contest therefore drops.

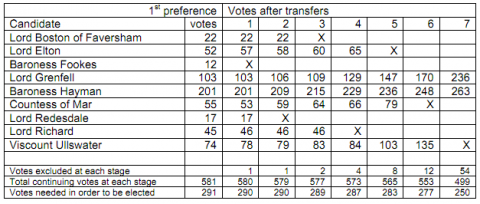

That is what happened when the House of Lords elected a new Speaker in 2006. Eventually the winning candidate was elected with 263 votes from the 581 initially cast: approximately 45 per cent.

For a candidate to have won in the first preference round, they would have needed 291 votes get more than half of the votes, as we explained in an earlier factcheck.

However, by the seventh round of voting, they only needed 250 votes to get a majority, and so to win.

** Under the AV system it would also be possible that a candidate could win over half of the votes in an early count, when they would have actually lost had all the next preference votes been counted through all possible counts.

The Constitution Society gives an example of this scenario with a mock election where a candidate wins a majority in an early count, who would not have won a majority had the election gone on to later counts.

CORRECTION

Concerning the question of whether AV will always elect the candidate preferred by the majority of voters, a reader pointed out to us that our statement ** on this was actually incorrect. It is not possible that a candidate who gets over half of the votes in an early count could have lost in a later count with all next preference votes are considered.

However, it is possible that under AV a candidate who is preferred by a majority of voters is not elected. For example, this could happen when a candidate who gets the majority of 1st, 2nd and 3rd preference votes combined is eliminated in the first count with the fewest 1st preference votes. They would thus not progress to the later counts where they would have attracted the combined 1st, 2nd and 3rd preference votes that would have allowed them to win a majority.

An example of this scenario is given in a blog by Dr. Hortela-Vallve, a lecturer in political science at the London School of Economics.