Does frequent youth unemployment negatively affect your wages later in life?

"By the age of 42, someone who had frequent periods of unemployment in their teens is likely to earn 12-15 per cent less than their peers"

Department for Education, 21 February 2012

Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg this morning spearheaded a Government scheme to help young people not in education, employment or training ('neets') back to work.

One claim on the impact of youth unemployment on earnings made it into several news outlets, including the Independent, Daily Express, Guardian, Daily Mail and Channel 4.

Join 72,953 people who trust us to check the facts

Sign up to get weekly updates on politics, immigration, health and more.

Subscribe to weekly email newsletters from Full Fact for updates on politics, immigration, health and more. Our fact checks are free to read but not to produce, so you will also get occasional emails about fundraising and other ways you can help. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy.

The Department for Education (DfE) stated in a press release that people who experienced frequent periods of unemployment in their youth could expect to earn 12-15 per cent less than their peers who did not experience the same periods of inactivity.

So where is the evidence for this?

Analysis

While the source of the claim was not made clear in the press release, the same statistic was in use as many as three years ago. The Prince's Trust's study on the cost of exclusion in 2007 employed the same figure, as well as the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) in evidence to the Work and Pensions Select Committee in 2010.

Both cite a 2004 academic study by Paul Gregg and Emma Tominey as the original source of the claim. The study asserts the statistic straight away in its abstract:

"Our results suggest a scar from early unemployment in the magnitude of 12% to 15% at age 42. However, this penalty is lower, at 8% to 10%, if individuals avoid repeat incidence of unemployment."

The authors use data from the National Child Development Survey (NCDS). This data set took children born in 1958 and collected data on the individuals at various points in their lives, including at the age of 42 in 1999/2000.

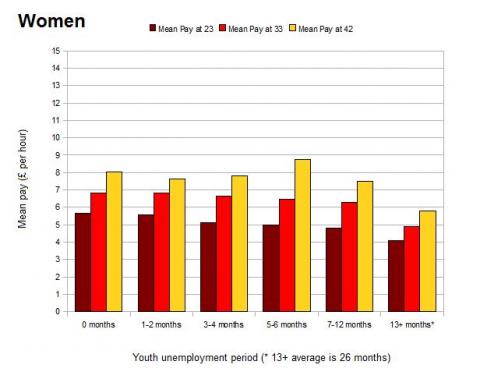

They went on to examine the periods of unemployment experienced by the individuals during various points of their lives: 16-23 (youth), 23-33 and 33-42. By comparing these figures with their earnings per hour at the various different ages they were able to calculate the average differences.

The summary of the findings can be graphed as below:

Looking at these charts, you'd be forgiven for thinking that the earnings gap between those frequently unemployed in their youth and those who were not was much greater than the DfE claims. For example, men who were never neet in their youth are shown to have approximately 45 per cent more cash in their pay packets by the age of 42 than those who were inactive for over a year.

However this raw data does not reflect differences in individual circumstances and backgrounds which might impact upon earnings that are unrelated to youth unemployment, such as parental involvment during childhood and any mental health issues.

Once the researchers controlled for these, they concluded that by the age of 42, long periods of unemployment (13+ weeks) between the ages of 16 and 23 could be seen as directly contributing to a drop of 15.4 in men's earnings when compared to his peers, and a shortfall of 11.6 per cent for women.

Once the study also controlled for periods of unemployment after the age of 23 however, the figures were 7.8 per cent less for males and 10.1 per cent less for females.

Of course, since the study was conducted in 2004 and based on data from people born in 1958, there are obvious limits to the estimates.

After contacting the author, Full Fact was also directed to recent research by the ACEVO Commission on Youth Unemployment, chaired by David Miliband. Their research was based on the 1970 British cohort study, and the findings were published this year.

The research applies the overall average amount of time spent out of education, employment or training (neet) and examines the gross weekly earnings from the ages of 30 to 34. They found that the average unemployed male at youth had 15.77 per cent lower earnings than average. This compared to a 17.07 per cent drop for females.

The findings are roughly similar to those of the Gregg/Tominey study and so lend further support to the charge that youth unemployment affects future earnings to the extent claimed by the DfE.

Conclusion

Both studies cited here use data collected from people who were born and grew up several decades ago. While this is of course necessary to measure the long-term effects of youth unemployment, it should be noted that the economic and social environments in which these cohorts first entered (or didn't enter, as the case may be) the labour market may be very different to those experienced by today's young people.

Both studies found a reduced average wage for individuals who had suffered more unemployment in their youth, to the tune of around 15 per cent for men in both cases and at differing levels for women.

From what is available, the assertion that frequent youth unemployment negatively affects wages later in life seems to be well founded.